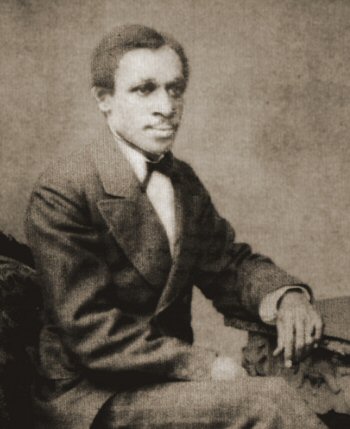

Teacher, news correspondent, and Fisk Jubilee Singer, Benjamin M. Holmes was born a slave around 1846 in Charleston, South Carolina and bound as an apprentice to a black tailor. Holmes was eventually bought by a man named Kaylor, who employed him as a hotel clerk in Chattanooga, Tennessee. While toting bundles around town for his master, Holmes used to study the letters on signs and doors and his boss’s measuring books, and by 1860 had taught himself to read and write.

After his owner and the rest of the staff joined the Confederate Army, Holmes was left minding the store. As Union troops approached Chattanooga in 1862, his white owners sold him to a trader who fed him a diet of cow’s head, boiled grits, and rice. While imprisoned in a slave pen, Holmes somehow managed to get hold of a copy of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and read it aloud. After Union troops occupied Chattanooga in the fall of 1863, Holmes volunteered his services as a valet to General Jefferson Columbus Davis, the Union commander of the Army of the Cumberland’s First Division, with whom he remained until the end of the war.

After the war, Holmes returned to Chattanooga and worked for a barber. When the barber died, his estate went to Holmes, making him the first black estate administrator in Tennessee. But the estate proved insolvent, and for his pains Holmes ended up with a three hundred dollar debt.

In 1868 Benjamin Holmes enrolled at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. By now he had already taught himself enough reading and mathematics to advance to the high school department in a mere two months. To earn his tuition, he taught a Davidson County school of sixty-eight pupils for thirty dollars a month. At a second school farther out in the countryside, his class was smaller, but the conditions more perilous. Once, someone fired a shot into the school while he was teaching a class.

Holmes returned to Fisk at the end of the summer and studied history, Latin, pedagogy and analysis. Holmes also became a deacon at Fisk’s Howard Chapel. As a member of the original Jubilees, Holmes became its most eloquent spokesman and sent weekly dispatches to Lewis Douglass’s newspaper, New National Era. , Holmes often clashed with Jubilee Singers director George White, and eventually arranged his own farewell concert in London, England to benefit the singers themselves. He quit the troupe and died of consumption in Nashville on October 9, 1875 at the age of 28.