Freeman Beach, near Wilmington, North Carolina, was one of two North Carolina beaches available to African Americans in the state during the Jim Crow era. The beach area, originally 99 acres of underdeveloped beachfront land near Myrtle Grove Sound, was acquired by Alexander and Charity Freeman, who were of mixed African and American Indian heritage. Alexander established himself as a fisherman on Myrtle Beach Sound in the 1840s. Legend has it that the beachfront resort community’s name came from fishermen who found the winds flowing off the Atlantic a refreshing respite from the hot sun. Freeman purchased the beach acreage in 1855 and over the years the couple enlarged their holdings to include 180 acres by the time of Alexander’s death in 1872.

By 1876, Alexander’s descendant, Robert Bruce Freeman Sr. bought an additional 2,500 acres for $1 an acre. At his death, Robert Bruce Freeman Jr. parceled the land in tracts, designed to be self-supporting waterfront properties, to a number of relatives. The beach community became home to a number of African American families, including generations of the Freemans, Wades, Rossers, Davises, McQuillans, and McNeils. Two of Robert Bruce Freeman’s heirs, Rowland Freeman and Nathan Freeman, played a major role in developing Seabreeze as a resort in the 1920s.

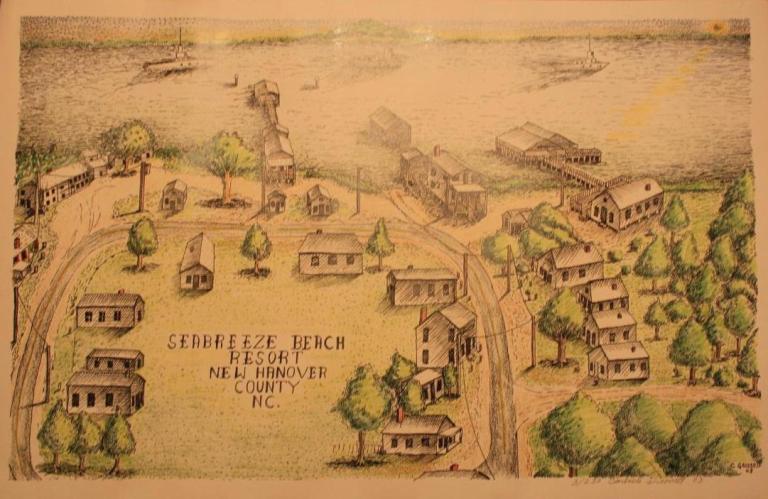

Between the 1920s and the 1960s Freeman Beach-Seabreeze developed rich cultural traditions and history as blacks from across eastern and central North Carolina traveled for miles to experience the wooden dance floors and jukeboxes. With Freeman Beach they found a place to vacation, relax, and play. From the 1920s through the 1960s, the beach had three hotels, ten restaurants, dozens of rental cottages, a boat pier, a bingo parlor, and a small amusement park, complete with Ferris wheel. During the summer months thousands of visitors flocked to the area.

Freeman Beach-Seabreeze suffered major damage from Hurricane Hazel in 1954. More insidious was beach erosion, which increased after the opening of the artificial Carolina Beach Inlet in 1952. By the late 1960s when desegregation opened other beaches to African Americans, Freeman Beach lost its summer visitors. Many of the older landmarks were blown down or washed away by other hurricanes in the 1990s, symbolizing an area long in decline.

Nonetheless Freeman Beach-Seabreeze survived as a close-knit residential community. Homeowners never abandoned the area and it attracted some retirees. These residents, including many Freeman descendants, established annual Heritage Day celebrations in the early 2000s, recalling the history and heyday of the resort. However, as the ownership of the property passed down to each new generation, the land parcels became increasingly smaller or were claimed by numerous descendants. Not surprisingly, people with ownership claims in the same plot of land began to contend for control. Further complicating the situation, in October of 2008, a development company called Freeman Beach LLC, which had no historic ties to the community, filed a petition for ownership claiming it had acquired control of numerous parcels and now had a majority interest in the land.