The brief entry for “Dorcas the blackmore” that appears in the Records of the First Church at Dorchester in New England, 1636-1734 suggests that Dorcas may have been one of the first enslaved persons to be freed in British North America.

On April 13, 1641, “Dorcas the blackmore” joined the Dorchester, Massachusetts Congregational church. John Winthrop, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, commented on the ease with which she was accepted into membership as based on her knowledge of scripture and her godly character. As Winthrop noted in his journal, “A negro maid, servant to Mr. Stoughton of Dorchester, being well approved by divers years’ experience, for sound knowledge and true godliness, was received into the church and baptized.” Like many other Congregational churches, Dorchester had a predominantly female congregation; between 1630 when the church was gathered and 1641 when Dorcas joined, for example, only seventy-four men had joined the church as compared with one-hundred and twenty-two women. Unlike the other women of Dorchester’s congregation, however, Dorcas was enslaved.

Twelve years after Dorcas joined the church an effort was made to secure her freedom. At a meeting on December 19, 1653, attended by nineteen of Dorchester’s male church members, a vote was taken asking “whether they were all willing that Dorcas was to be Redeemed.” If the vote was yes, Ensigne Foster and two of the church’s deacons decided that they would go to Boston and ask the magistrate what might be done to free Dorcas. For good measure, Foster and the church’s deacons decided that they would take an ox and a cow with them as partial payment for Dorcas’s freedom. In addition, if more funds were required to secure her freedom, the men assembled that day agreed that they would “laye down for the present” whatever sum of money was required until it could be raised “from the whole church by Contribution or otherwayes.” The vote in support of attempting to redeem Dorcas was “affirmative.”

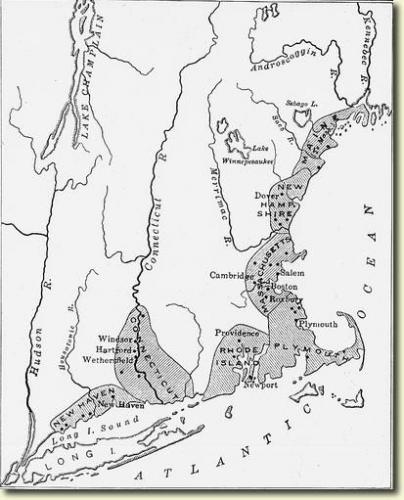

Ironically, Dorcas joined the Dorchester congregation the same year that Massachusetts legalized the ownership of Africans and Indians in its Body of Liberties. It was the first colony in British North America to legalize slavery. Slavery remained legal in Massachusetts until the 1780s when the institution was declared incompatible with the bill of rights contained in the new Massachusetts state constitution.

Dorcas next appears in the church records in August 1676. The entry states that “Dorcas the negar being formerly a member of this church was dismissed to joyn to the first church at Boston.” Being dismissed from a church was a formality within the early Congregational church and meant that you were free to covenant with or join another congregation. According to the Records of the First Church in Boston, “Dorcas a nigro from Dorchester” was admitted by letter of dismission to Boston First Church on July 29, 1677, one year after her dismissal from Dorchester.

Although Dorcas’s situation is unusual in that few female church members were enslaved and therefore not in need of manumission, the case of “Dorcas the blackmore” is significant because it demonstrates that church membership and affiliation could bring tangible benefits for women, especially for those women whose reputation for knowledge and godliness was well-known. In Dorcas’s case, the members of Dorchester First were powerful allies in efforts to break the bonds of her enslavement.