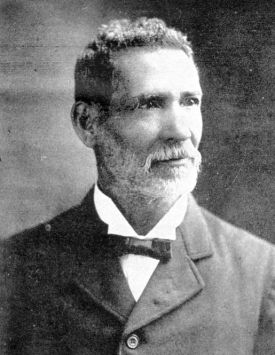

Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes was a prominent editor, author, and civil rights activist from New Orleans, Louisiana. He is best known for his work in Plessy v. Ferguson, the most important civil rights case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 19th Century, and a book he authored about the history and culture of Creoles in Louisiana.

Desdunes was born November 15, 1849 in New Orleans. His father was a Haitian exile, and his mother was Cuban. Desdunes came from a family that owned a tobacco plantation and manufactured cigars. He was a law student at Straight University in the early 1870s. He also worked for the United States Customs House in New Orleans first as a messenger from 1879 to 1885, and as a clerk from 1891 to 1894, and again from 1899 to 1912.

Desdunes grew up and experienced young adulthood in New Orleans at a time when public facilities and public schools were integrated. The political environment in Louisiana, however, began to change in the late 1880s. The State Legislature of Louisiana began enacting laws that segregated blacks and whites in public spaces.

In 1889 Desdunes became editor of the Crusader, a weekly black newspaper printed in French and English which was created to inform and rally black and Creole community leaders to challenge the encroaching segregationist laws. He and the publisher, Louis A. Martinet, called for equal rights and urged legal action against segregation.

Through the Crusader, Desdunes and Martinet helped develop a new national civil rights group, the American Citizens Equal Rights Association (ACERA). A delegation of ACERA addressed the Louisiana Legislature in 1889 but with no effect. Within weeks, most black ACERA members dropped out due to white intimidation and the Legislature passed Act 111 of 1890 (“The Separate Car Act”), which segregated railroad passenger cars for the first time.

Desdunes and Martinet formed a second committee, Comité des Citoyens (“Citizens Committee”), to fight the new segregation law. They enlisted the support of a wealthy Creole, Aristide Mary, who would prove critical in funding the upcoming legal battle against segregation. .

Rodolphe Desdunes’s son, Daniel, challenged the law in February 1892. He was arrested, but was acquitted since his train travel was interstate. Four months later another Creole, Homer Plessy, challenged the law by travelling within Louisiana. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled against Plessy in 1896. That case set the legal precedent which allowed the establishment of “separate but equal” facilities across the United States.

Desdunes never again became involved in legal or political activity against segregation. In 1911 he wrote Our People and Our History: Fifty Creole Portraits, which was first published in French in 1911. The book recorded the lives of prominent Creoles in New Orleans.

Desdunes also returned to his job at the New Orleans Customs House. While supervising the weighing of cargo on a ship in 1911, granite dust blew in his eyes leaving him mostly blind. He retired in 1912.

Desdunes, who preferred to speak Creole and enjoyed cigars, spent the last 17 years of his life in various stages of blindness. He died from cancer of the larynx on August 14, 1928, at the home of his son, Daniel, in Omaha, Nebraska.