The Black Maroons of Florida, also known as Black Seminoles, Seminole Maroons, and Seminole Freedmen, were a community derived from Runaway slaves who integrated into American Indian culture. They were mostly Gullah fugitives who escaped from the rice plantations in South Carolina and Georgia who joined with the newly formed Seminole groups who broke away from the Muskogee or Creek people. Both groups were fleeing the decimation of their cultures and people by European-brought violence and disease and sought refuge in the Florida forests. Initially they settled in north-central Florida but eventually extended their settlements south into the Everglades. Although Spain claimed all of Florida, the Seminoles and their black maroon allies survived in the vast tropical wilderness of jungles and malaria-ridden swamps. They defended themselves and preserved their freedom against Spanish and later U.S. military control.

Black maroons and the Seminoles also shared numerous cultural similarities regarding cuisine, tribal dancing, and dwelling construction There were differences such as religious practices and languages—the Seminoles spoke Creek and the maroons spoke Afro-Seminole Creole. These differences, however, did not prevent intercultural marriages or military alliances. The Florida Native American communities protected Black Seminoles from re-enslavement. In return, they provided manpower in military conflicts with the Spanish or Americans. Overall, the Florida Maroons lived independently of the Indians without oversight.

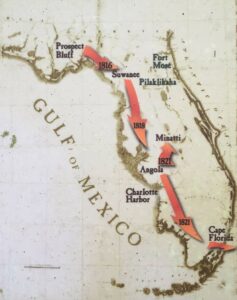

Free maroon settlements emerged in Florida in the early 1700s, the earliest being Fort Mose near St. Augustine in 1738. By that point more than 100 freedom seekers built a fortified town named Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose. Fort Mose became the site of the first free black community in what is now the United States. Spain, recognizing the need for allies against both the British and later the Americans after 1790, promulgated a series of royal decrees promising freedom to all enslaved persons who reached Florida as long as they embraced Catholicism. The Spanish noted that slavery in Florida had been abolished in 1693.

During the first of two so-called Seminole Wars, Blacks and Indians fought side by side against American incursion into the region. Spain sold Florida to the United States in 1819 but even before the transfer, in 1818, General Andrew Jackson sent U.S. forces down the Apalachicola River to defeat and destroy Maroon, Seminole, and Creek communities. They destroyed the Maroons’ and Indian villages. Black Maroons and the Seminoles responded by moving further south into the more remote forests of central and southern Florida. Many Black Seminoles left Florida for Andros Island in the Bahamas.

In 1835, during the Second Seminole War, the Maroons and Seminoles continued their resistance, mounting a full-scale guerrilla war which ended in 1841. More than 1,500 white American soldiers died in this war. Nonetheless, the Seminoles and their surviving black allies, were defeated and removed from Florida beginning in 1842 to Indian Territory (what is now Oklahoma).

Today, the largest number of “Black Maroons” live on Andros Island, where their ancestors escaped from Florida after the First Seminole War. Others even ended up in Mexico.