The Colored Carnegie Library was a segregated branch of the Houston Lyceum and Carnegie Library (later the Houston Public Library). It opened in 1913 in Houston’s Fourth Ward and was one of the first public libraries for African-Americans west of the Mississippi River. It was also one of twelve segregated public libraries originally funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie between 1908 and 1924.

The Colored Carnegie Library’s story began in 1907, when Houston’s public library denied service to a group of African American teachers. The city had received $50,000 from Andrew Carnegie in 1899 for its public library, which opened in 1904 on the corner of McKinney and Travis (now Main) streets. But while nearly 40% of Houston’s population at time (44,600 people) were African American, the city offered no comparable library services to its black citizens.

In response, a committee led by educator Ernest Smith opened a small, one-room library in the Fourth Ward’s Colored High School in 1909. They also approached the city’s Chief Librarian, Julia Ideson, and Mayor H. Baldwin Rice to request a separate “colored library” grant from Carnegie. Following additional support from Booker T. Washington (whose assistant, Emmett J. Scott, was Houstonian), their application was approved in 1909. Carnegie donated $15,000 and the Colored Carnegie Library opened in 1913.

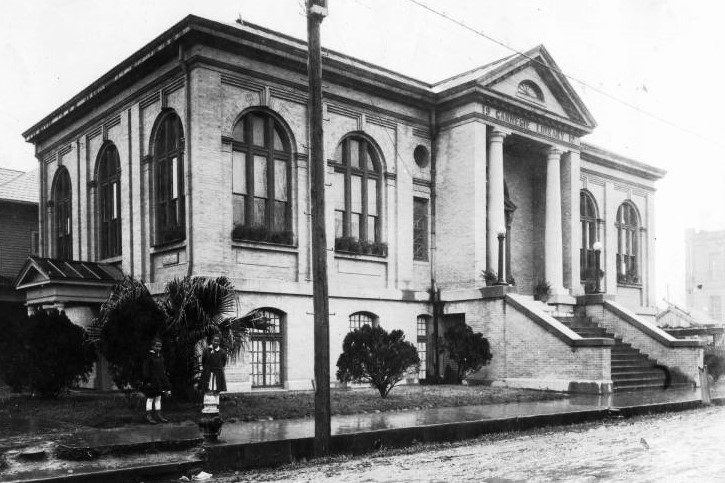

The new library quickly became a symbol of civic autonomy for Houston’s African-Americans. Its architect was William Sidney Pittman, son-in-law of Booker T. Washington. Although the Colored Carnegie Library received tax support from the city, it did not operate as a branch of the city’s (white) public library. It was governed by the Colored Carnegie Library Association, an independent board of African American leaders.

The library stood at the corner of Frederick and Robin streets, in the heart of the city’s Fourth Ward, then considered Houston’s “colored district.” It was near several public schools and directly across from one of the community’s largest churches, the Antioch Baptist Church. The library’s opening in 1913 made headlines in black newspapers across the country, including the New York Age.

The Colored Carnegie Library remained vital to Houston’s African American community for nearly five decades. Though it reopened as a branch of the city’s main library in 1921 (thereby dissolving its independent board), the “Colored Carnegie Branch” organized many reading programs and book clubs, accumulated important collections of African American literature and history, hosted many guest speakers, helped local teachers and schoolchildren, and offered night classes for adults. Local organizations and clubs gathered regularly in the library’s meeting rooms, among them the Negro Art Guild of Houston and the local branch of the NAACP. Branch librarians included Bessie Osborne, James Hulbert, Florence Bandy, and Willie Bell Anderson.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Houston Public Library expanded its services to African Americans. They opened a branch at Emancipation Park, installed deposit stations at many black public schools and launched a separate bookmobile service in the 1950s. Though Houston desegregated its libraries in 1953, the Colored Branch continued to serve a predominantly African American clientele for most of its remaining years. Use of the library declined throughout the 1950s however, until the Colored Branch finally closed in 1961. The building was demolished the following year during the city’s Clay Street extension project.