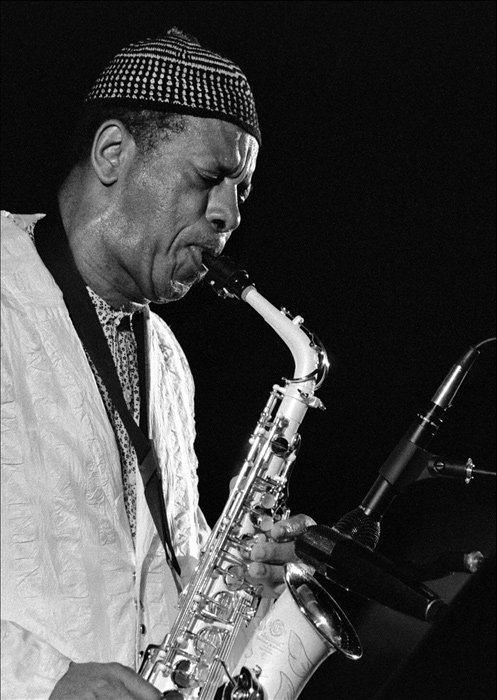

It may be impossible today to understand fully the shock and outrage which alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman’s 1959 arrival in New York caused within the jazz community. Coleman’s innovations freed his quartet from traditional structures of form, chordal harmony, tonality, and rhythm, and though his work has sharply divided opinion, he is widely acknowledged as having transformed the way in which jazz is heard and performed.

Born in 1930 in Fort Worth, Texas, Coleman began playing tenor saxophone in rhythm and blues (R&B) bands, his own style rooted in the bebop idiom. Though undocumented, his early development suggests something unique – Coleman was assaulted and his tenor saxophone destroyed after a particularly off-putting dance solo in Baton Rouge. In 1949 Coleman settled in Los Angeles where he worked as an elevator operator and independently studied music theory. On the alto saxophone, which remains his primary voice, Coleman developed a plaintively raw and vocalized tone, exploring micro-tonalities and speech-like cries. In Los Angeles Coleman befriended drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins, as well as trumpeter Don Cherry, all of whom would later become mainstays in Coleman’s ground-breaking Atlantic quartets. In 1958 Coleman found a willing partner in pianist Paul Bley, and with Higgins, Cherry, and bassist Charlie Haden the quintet recorded a live performance at the Hillcrest Club, The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet.

Coleman’s 1959 debut at the Five Spot in New York City was a sensation. Further inciting the controversy were Coleman’s studio albums recorded for Atlantic between 1959 and 1961. Coleman’s pianoless quartet – with Cherry, Haden, and alternating Higgins and Blackwell – found expansiveness in economy. Creating deep webs of implied harmony, the band improvised melodic themes which evoked musics ranging from the blues and folk music to advanced western counterpoint. In this period Coleman’s quartet produced such classic recordings as The Shape of Jazz to Come, This is our Music, and Change of the Century. In 1960 Coleman recorded the pivotal double quartet album Free Jazz, augmenting his band with Eric Dolphy, Freddie Hubbard, and Scott LaFaro.

In the winter of 1962 Coleman withdrew from the active music scene, meanwhile teaching himself trumpet and violin. When Coleman returned in 1965 he did so with a noteworthy new trio featuring bassist David Izenzon and drummer Charles Moffett. The trio recorded two nights of live material for Blue Note which composed At The Golden Circle, Stockholm: Volumes 1 & 2. Coleman worked in a variety of formats throughout the 1960s, and in 1972 he recorded Skies of America with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Founded in 1975, Coleman’s electric ensemble, Prime Time, features multiple electric guitars, basses, and drums, including his drummer-son Denardo Coleman. With Prime Time Coleman established the theoretical musical framework of “Harmolodics,” a term which has, generally, defied any concise or clear explanation. Coleman became increasingly visible in the 1980s, in large part due to the landmark collaboration with guitarist Pat Metheny, Song X. Recently Coleman has recorded sparingly, although 2006’s Sound Grammar received the Pulitzer Prize for Music. In 2007 Coleman was honored with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Coleman died from cardiac arrest on June 11, 2015 in Manhattan. He was 85.