Fewer than half of Cincinnati, Ohio’s Black population remained in the city after the 1829 white riots. Most had left. Many of the 1,100 who stayed were unusually poor, unable to finance emigration to safer places such as surrounding towns, farther west, or to Canada.

The small black community regrouped, rebuilt the razed section of town, and restored community organization. Nonetheless the exodus had decimated community institutions such as church leadership and members, political leaders, teachers and business people.

The white violence in 1829 had spawned one unexpected effect, however. At Lane Theological Seminary, a new Presbyterian institution nearby, a group of white students and some faculty, shocked by the brutality, held a week-long debate on slavery and abolition. It ended in a two-fold consensus: one, immediate abolition was an absolute necessity for all Christians; and two, so-called repatriation efforts to Africa were fundamentally misguided. Their published opinions spread throughout the abolitionist movement. The seminary was led by Lyman Beecher, whose daughter Harriett would later shake the world with her literary indictment of slavery, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In response to growing abolitionist sentiment, in January of 1836 some of Cincinnati’s prominent white residents organized an anti-abolitionist meeting, reportedly attended by over 500 men. They called for an end to abolitionist agitation and strict enforcement of the Black Laws. Additionally, white day workers along the riverfront were again complaining about competition for common labor jobs with black workers.

In April of 1836, James Gillespie Birney, a former slaveholder from Alabama, arrived in Cincinnati to open the Cincinnati Weekly and Abolitionist. The anti-slavery newspaper reached readers on both sides of the Ohio River, threatening both Kentucky slaveholders and the Cincinnati merchants who depended on trade with them.

Within two weeks, a white mob invaded the largely black First and Fourth wards. Led again by mainly Irish immigrants, the mob burned down a Black tenement, killing an unknown number of African Americans. The mob attacked residences and businesses and beat people on the streets. The crowds also targeted known white abolitionists. The mobs ruled the streets until Ohio Governor Robert Lucas intervened and declared martial law.

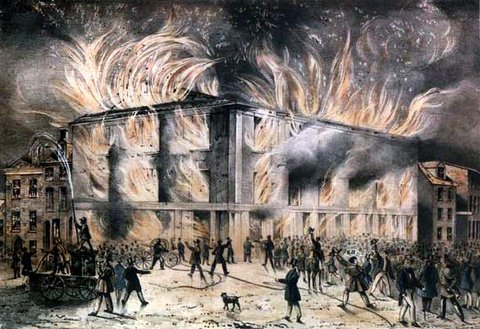

White rioting again broke out on July 5, set off by a white-Black altercation at the traditional Fourth of July celebration. Whites gathered and attacked the demonstrators. Sporadic violence continued for one week. On July 12, 40 white men broke into the building where Birney’s printing press was located and destroyed it. Anti-abolitionists posted “wanted posters” all over the city offering $100 for Birney’s capture and delivery to pro-slavery hooligans, who called themselves “Old Kentucky.”

Backed by a $2,000 guarantee from the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, Birney published again. Pro-slavery whites responded, led by Cincinnati mayor Samuel A. Davis. At an angry meeting he chaired on July 23, the city promised to shut down all abolitionist publications. One week later, on July 30, another white mob attacked Birney’s new press and destroyed it. They also attacked an area of the city known as The Swamp, populated mainly by poor African Americans, burning homes and assaulting residents. The mayor reportedly praised the actions of the mob, many of whom were Kentuckians who crossed the Ohio River into Cincinnati.

The riot was finally suppressed by organized local volunteers who for three nights patrolled the streets. No arrests were made despite numerous deaths. National reaction was strong. Abolitionists were outraged by the brutality of the riots; the movement in fact gained national traction as accounts of the violence spread. Harriett Beecher’s horror and revulsion as an eyewitness made its way into her future novel. Salmon Chase, later Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, was profoundly affected by the violence and it shaped his growing abolitionism.