The Chicago Freedom Movement, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, and Al Raby, was created to challenge systemic racial segregation and discrimination in Chicago and its suburbs. The movement, which included rallies, protest marches, boycotts, and other forms of non-violent direct action, addressed a variety of issues facing black Chicago residents, including segregated housing, educational deficiencies, income, employment, and health disparities based on racism and black community development. The Chicago Freedom Movement, the most ambitious civil rights campaign in the northern United States, lasted from mid-1965 to early 1967 and is credited with inspiring the Fair Housing Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1968.

The Chicago Campaign began in July 1965 when local civil rights groups invited Dr. King to lead demonstrations against segregation in education and housing as well as employment discrimination. Chicago activist Albert Raby, leader of the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), asked the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to join them in a nonviolent campaign to achieve fair or open housing in the city. Community organizers pointed to Chicago’s history as one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation. Through lending discrimination and, in some instances, outright violence and intimidation, African Americans were kept out of the vast majority of predominately or all-white middle class neighborhoods in the city. Activists hoped that by changing the laws and practices to allow “open housing,” the ability of black homeowners to purchase homes in any area they could financially afford, blacks would gain access to improved housing, better schools, and greater job opportunities.

On January 7, 1966, King and the SCLC announced plans for a Chicago Freedom Movement, a campaign that marked the expansion of their civil rights activities from the South to northern cites. King and his family moved to a Chicago slum at the end of January to bring attention to housing conditions of tens of thousands of black Chicago residents while CCCO organized mass nonviolent protests in the city.

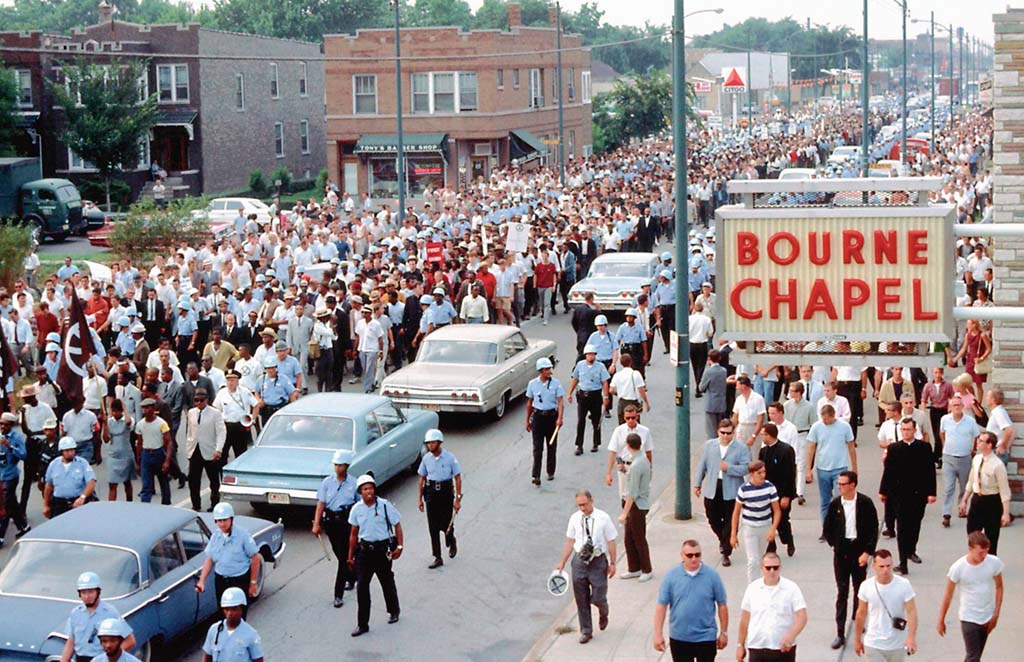

To target racial demonstration in housing and employment, SCLC launched Operation Breadbasket and placed it under the leadership of twenty-five-year-old SCLC organizer, Rev. Jesse Jackson. Operation Breadbasket targeted companies and corporations working in African American neighborhoods that nonetheless refused to hire black employees. The parallel campaigns gained momentum through boycotts, demonstrations, marches, and the race riots that erupted on Chicago’s predominately black West Side in July 1966. On August 5, 1966, during a march at Marquette Park, an all-white Chicago neighborhood, to promote open housing, black and white demonstrators were met with intense racially-fueled hostility. Bottles and bricks were thrown at them. Dr. King, leader of the march, was struck by a rock. King admitted in a post-march interview that he had seen many anti-civil rights demonstrations in the South but none that was as hostile and violent as the one he experienced in Marquette Park.

King faced the challenge of mobilizing Chicago’s diverse African American community of nearly one million people. He cautioned against further violence and worked to counter the mounting resistance of working class whites who were fearful of the impact of open housing on their neighborhoods. By August, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley sought a way to end the demonstrations. After negotiating with King and various housing boards, an agreement was announced on August 26, 1966, in which the Chicago Housing Authority promised to build public housing in predominately white areas, and the Mortgage Bankers Association agreed to make mortgages available, regardless of race or neighborhood. After the agreement was announced, some SCLC staff stayed behind to assist with the housing programs and voter registration. Dr. King stayed in Chicago until January 1967, while Jackson settled permanently in the city to lead the Chicago branch of Operation Breadbasket. In 1968 the U.S. Congress passed the 1968 Fair Housing Act, as the most direct result of the Chicago Freedom Movement.