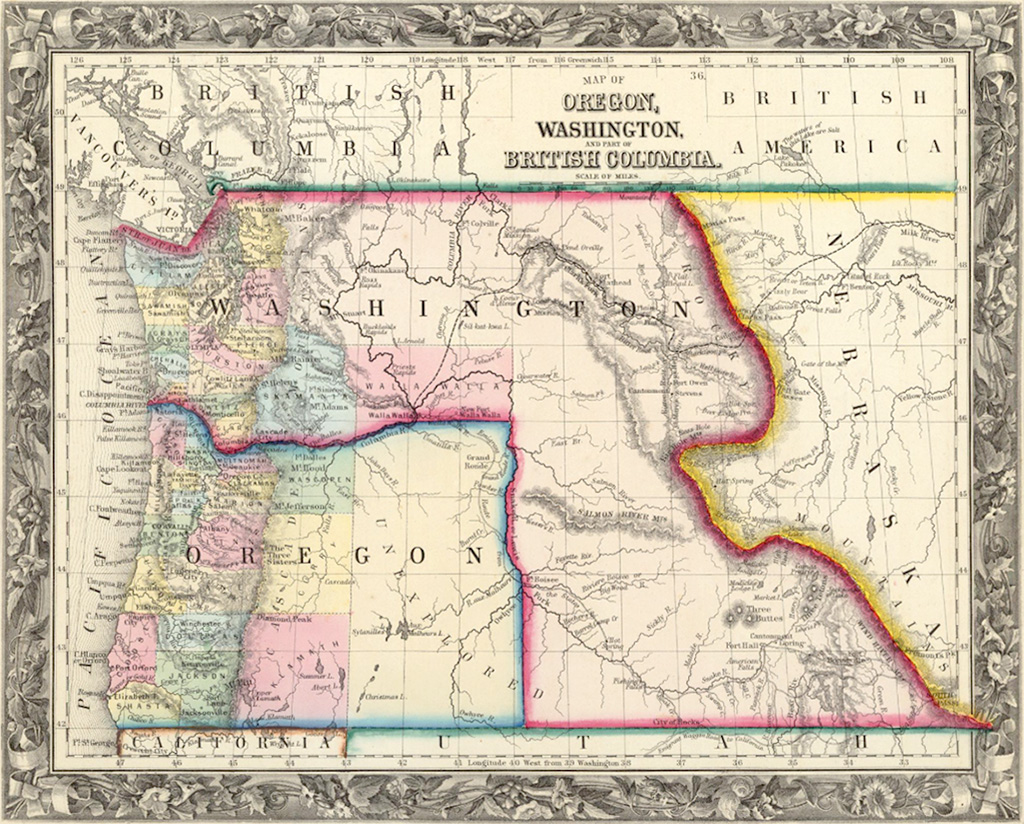

Few people connect Washington Territory with slavery. However one incident in 1860 was a reminder that the peculiar institution reached the pre-Civil War Pacific Northwest. In the account below, historian Lorraine McConaghy describes the saga of Charles Mitchell whose attempted escape from slavery in a vessel sailing between Olympia, Washington Territory and Victoria, British Colombia, touched off an incident that had international repercussions.

In 1847, Charles Mitchell was born at Marengo Plantation on Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland. His father was a white oyster fisherman named Charles Mitchell; his mother was a young black house slave whose name is unknown to us. We do not know anything about the relationship between Charles Mitchell senior and the house slave, but it may have been consensual or even loving since the boy was named for his father. In any case, slavery ran through the female line, and so Charles Mitchell was born a slave, despite his father’s freedom.

Slaves had been born, toiled, and died at Marengo Plantation for more than 150 years. Marengo had been named by the grandson of the plantation’s founder, Jacob Gibson, in admiration for a victory of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Gibson family presided over Marengo, and the plantation’s fields grew tobacco profitably until the soil was depleted. The land was then switched to wheat. In about 1800, there were three dozen slaves on Marengo Plantation; in the 1850 slave census, there were thirteen. Charles Mitchell’s mother was one of them, the personal servant of Mistress Rebecca Gibson; the two women had grown up together.

It is likely that the young black woman’s sister, parents, and grandparents, along with Charles, were all living as a family within the slave quarters. During the great cholera epidemic of 1850, Charles’ mother fell ill and died. According to Gibson family tradition, Rebecca Gibson asked the dying woman what she could do for her. “Take care of my Charlie,” was her reply, and Rebecca answered, “I will.”

The Gibson family of Marengo Plantation had been inter-marrying with the Tilton family of Tilton Hill in Wilmington, Delaware for generations. Unlike the Gibsons, the Tiltons were not tied to the land. Instead, they were professional men: physicians, attorneys, and surveyors. Dr. James Tilton and his wife Frances Gibson Tilton moved the family from Delaware to Indiana in 1827 to find new opportunities on the western frontier. Their son, also named James Tilton, was ambitious. He apprenticed as a surveyor, joined the U.S. Navy, and fought in the Mexican War, twice wounded. But James Tilton really made his fortune as a political man, campaigning aggressively in Indiana for the election of Franklin Pierce to the presidency. In return, the successful President Pierce awarded Tilton a patronage prize, appointing him surveyor general of Washington Territory.

James Tilton, his wife, their young children, his widowed sister and her children, and an Irish cook prepared for the long journey from the eastern seacoast of the United States to Olympia, the capital of Washington Territory. Rebecca Gibson had decided to keep her promise to her dead slave by giving Charles Mitchell to James Tilton to take to the distant Pacific Northwest.

The Tilton household arrived in Olympia in the spring of 1855. Tilton took up his responsibilities as surveyor general and his family entered the tiny world of territorial society. As a Pierce appointee, he was comfortable in the territory, participating fully in the Democratic politics of this distant place.

In 1860, the federal census taker found Charles Mitchell, a boy of 12, living with the extended Tilton family in Olympia, Washington Territory. He attended school and church, and made friends among the Indian and mixed race Indian children. During the spring and summer of that same year, while running errands for the Tilton family in Olympia, Charles Mitchell was approached in secret by representatives of the black community in the Crown Colony of Victoria.

At that time, Victoria was 25% black, peopled by a migration of black families from California. A man named William Jerome had briefly lived in Olympia and he had noticed Charlie, a lonely black child in a white family to which he did not belong. In Victoria, Jerome turned for help to James Allen, the cook on board the mail steamer Eliza Anderson, and another man named William Davis. These three black men twice took Charlie Mitchell aside. They told him that he was a slave in the Tilton family, suggested that he could become a fugitive, that they would help him get free, and that he could live in a loving black community in Victoria. It was not an easy decision. Charlie had to decide to leave the only home he could remember for an uncertain future. But on September 24, 1860, he sneaked out of the Tilton home at dawn to board the Eliza Anderson, where James Allen hid him in the pantry of the ship’s galley.

The steamer headed north to Steilacoom, then to Seattle, and on to Victoria. Along the way Charlie was discovered, and Captain John Fleming and First Mate Woodbury Doane decided to make him work for his passage. They then intended to take him back to James Tilton in Olympia.

In 1860 Washington Territory, Charles Mitchell’s status was ambiguous. In the 1857 Dred Scott decision, the U.S. Supreme Court had found that a slave had no status before the law, and that the U.S. Congress had improperly passed legislation that interfered with the relationship of a master and a slave by passing the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Instead, the Court held, a white man’s ownership of a black slave was a property relationship, guaranteed by the Constitution. Until a territory became a state and could pass a referendum by popular sovereignty for or against slavery, a white man’s black property was his to keep. Washington Territory’s legislature passed a resolution expressing their approval of the Dred Scott decision and of by-then President James Buchanan’s pro-slavery administration. In short, James Tilton owned Charles Mitchell, and so the captain and first mate of the Eliza Anderson intended to restore that relationship.

Charlie Mitchell was locked up in the ship’s lamp room when the Anderson steamed into Victoria harbor, but the ship was met by a hundred black and white residents who were in on the conspiracy and eager to welcome the boy. The three black men – Jerome, Davis, and Allen – hurried off to speak with barrister Henry Crease, who was sympathetic to the black community in Victoria. Crease had the three dictate and swear to affidavits stating the following: that Mitchell was a slave, that he belonged to James Tilton, that he had tried to run away before but had been too closely watched, that he was trying to escape captivity in Olympia, Washington Territory, United States of America, fleeing to freedom in the Crown Colony of Victoria, that he had stowed away on the Eliza Anderson, and that Captain Fleming had locked him in the lamp room to prevent him from “obtaining his freedom by setting foot on British soil.” Crease secured a writ of habeas corpus to seize Charlie Mitchell from the steamer, arguing that the captain had no right, in British waters, to confine Charles Mitchell against his will.

Back on the dock, Victoria’s sheriff served the writ and Charles Mitchell was freed to his custody, to spend the night in jail. In court the following morning, Mitchell was freed. There was no slavery anywhere in the British Empire, and the judge freed Charlie to the custody of Victoria’s black community.

When James Tilton learned that Mitchell had run away, he joined Captain Fleming in lodging a protest. Washington Territory’s acting governor Henry McGill summarized these documents to the U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass. In Olympia, Tilton gave a lengthy interview to the newspaper Pioneer and Democrat, which summarized his point of view. Newspapers from the Victoria Colonist to the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin reported this remarkable flight – the only fugitive slave to flee a master in Washington Territory. The editor of the Steilacoom newspaper wrote thoughtfully, “Our proximity to the British Possessions on this Coast affords the same facilities to an underground railroad that the Canadas do on the Atlantic.”

The language of this paper trail is interesting. James Tilton was called a master, an employer, a guardian, an owner, and a man “like a father to [Charlie].” Conversely, Charles Mitchell was called a slave, an employee, a ward, property, and “like a son to [James Tilton].” Tilton claimed that he had promised his cousin Rebecca Gibson that he would raise Charles Mitchell, schooling and churching him, and then have him trained to work as a steward on a steamer in Puget Sound. It was assumed that one day Washington would enter the union as a free state and Charles Mitchell would be a free man. In the last analysis, Charles Mitchell was owned and was not free to come and go as he pleased – severed from his family, a black child in a white household.

It is not clear what became of Charles Mitchell. He may have returned to Baltimore, Maryland after the conclusion of the Civil War to find his aunt, since there is a Charles Mitchell, identified as “mulatto,” in the 1870 census there. Afterward, he may have returned to Victoria. According to a newspaper report, a “colored man named Charles Mitchell” left Sooke with a white man and a canoe laden with cedar shingles on Sunday, February 13th, 1876. Five days later, the canoe and some of the shingles washed up on shore at Beachy Bay at the foot of Church Hill, but there was no sign of either man. A second canoe sent out to search for them found nothing. He left a wife and three children. This is most likely the Charles Mitchell who fled slavery in Washington Territory in September 1860, and is best known for being the first and only fugitive slave to travel from Washington Territory to the Crown Colony of Victoria on the Puget Sound Underground Railroad.