To escape enslavement on a plantation near Richmond, Virginia, Henry “Box” Brown in 1849 exploited maritime elements of the Underground Railroad. Brown’s moniker “Box” was a result of his squeezing himself into a box and having himself shipped 250 miles from Richmond, Virginia to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Henry Brown, born enslaved in 1816 to John Barret, a former mayor of Richmond, eventually married another slave named Nancy and the couple had three children. Brown became an active member of Richmond’s First African Baptist Church where he was known for singing in the choir. In 1848 Brown’s wife and children were abruptly sold to away to North Carolina. Using “overwork” (overtime) money, Brown decided to arrange for his freedom.

He constructed a wooden crate three feet long and two feet six inches deep with two air holes. With help from Philadelphia abolitionists, he obtained a legal freight contract from Adams Express. This freight company with both rail and steamboat capabilities arranged to ship his package labeled “Dry Goods” to Philadelphia. The package was a heavy wooden box holding Brown’s 200 pounds.

Henry “Box” Brown loaded himself in Richmond on March 22, 1849, and from there the package moved via horse-drawn carriage to the rail depot of the Richmond-Fredericksburg-Potomac Railroad. Brown’s freight car was off-loaded 56 miles north on the Potomac River’s Aquia Landing and then placed aboard a Potomac River steamboat and shipped 40 miles upriver into Washington D.C. Here, the “package” transferred to the Washington & Baltimore Train Depot and passed by rail through Baltimore, arriving 149 miles later in the Port of Philadelphia on March 24, 1849. A local Philadelphia carting firm delivered “the package” to the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society. Delivered in 27 hours, Brown was welcomed by Philadelphia abolitionists led by Underground Railroad organizer, William Still.

Brown carried a bladder filled with drinking water and a gimlet if he needed to drive more air holes in the box. Tossed about and turned upside down when moved by drayage men aboard a steamship, he wrote that “veins on his temple grossly distended with eyes swelling and popping pain.” A fellow passenger, tired of standing, righted the box and had a seat, unaware of its human cargo. When the freight package opened, Henry “Box” Brown started singing a song of celebration and thanksgiving. After his escape “Box” Brown became a popular abolitionist speaker.

Upon passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, Brown left the United States for England. Here as a featured speaker in England’s abolitionist circuit he used visual aids such as a landscaped “moving panorama,” a painted scroll showing a lengthy series of related inter-connected panels painted on a single cloth.

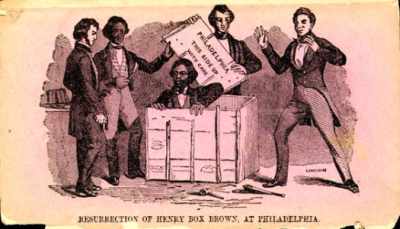

By 1875 Brown had returned to New England and married a second time. He lectured under the name Professor H. “Box” Brown until his death. Brown is believed to have died around 1889. Samuel Rowse’s, Resurrection of Henry “Box” Brown lithograph, immortalizes Brown’s 1849 journey.