On Christmas Day, 1837, during the Second Seminole War, the Africans and Native Americans comprising Florida’s Seminole Nation defeated a superior U.S. fighting force. In more than half a century of Florida invasions, this was the worst defeat the Seminole Nation inflicted on the American Army, which was the strongest military force on the continent at that time. This victory, though long omitted from history books, is a milestone moment in American history.

Spain claimed Florida during the 17th and 18th centuries, but so loosely governed it that it attracted untold numbers of pirates, adventurers, and – in particular – runaway slaves from Georgia and Carolina plantations. Spanish colonial officials offered sanctuary to escapees from the British colonies.

After the United States became an independent nation and plantation agriculture – and slavery – increased, more runaways sought out Florida and freedom. After 1776, Creek dissidents known as “Seminoles” (derived from the Spanish word for “runaways”) who broke away from the Creek nation also sought refuge in Florida.

There they were welcomed by the Africans, who taught them methods of rice cultivation learned in Senegambia and Sierra Leone.

As the Africans welcomed and incorporated the Seminoles and their descendants who had fled to Florida, the two peoples forged an economic and military alliance. U.S. slaveholders in turn confronted what was for them a nightmare: Florida now served as a beacon that offered additional escapees shelter and military assistance in preserving their freedom.

Planters demanded U.S. military intervention; by 1811, President James Madison authorized covert slave-catching invasions into Spanish Florida. In 1816, General Andrew Jackson, probably supported by President James Monroe, ordered an attack to “restore the stolen negroes to their rightful owners.” This invasion destroyed “Fort Negro” on the Apalachicola River, the center of a region where hundreds of Seminoles and runaway slaves had villages, farms, and cattle. In 1818, Jackson invaded Florida again, seizing fugitive slaves as well as free black women and men, returning them to the United States.

In 1819, the United States government purchased Florida from Spain for $5,000,000; this purchase, however, did not mean pacification. For the next four decades the U.S. Army fought three Seminole Wars to bring that Indian nation under control and to end the Seminole practice of sheltering fugitive slaves. These wars involved the seizing of women and children as hostages and destroying crops and villages.

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842) cost 1,500 U.S. military lives and over $40,000,000 from the U.S. Treasury, eight times the initial purchase price of Florida. These wars, however, were the largest and longest slave revolt in U.S. history, and were the strongest military alliance between African Americans and Indians in North America. Numerous military figures such as Osceola, Wild Cat, and John Horse led the Seminoles.

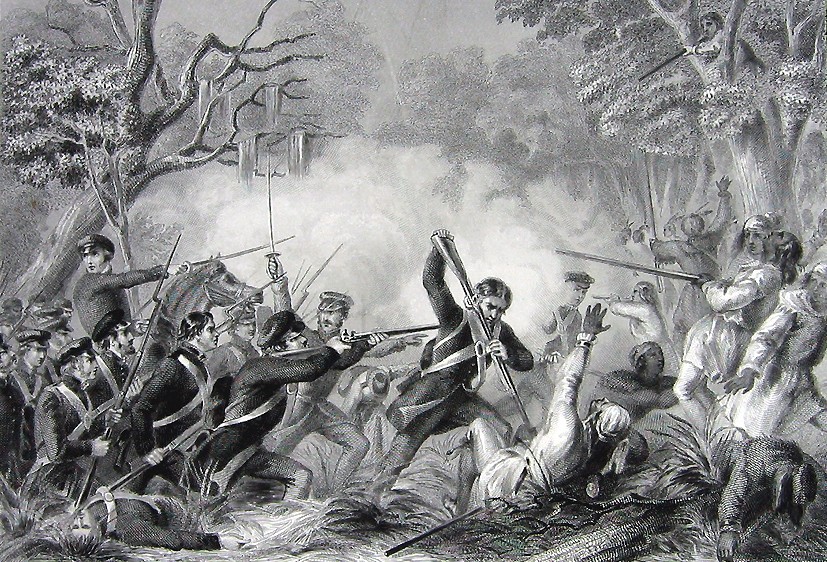

On Christmas Day, 1837, on the northeast corner of Florida’s Lake Okeechobee, about 450 Seminole soldiers and their black allies awaited Colonel Zachary Taylor and his 70 Delaware Indians, 180 Tennessee volunteers, and 800 U.S. infantrymen. Initial Seminole fire sent the Delaware fleeing. Tennessee riflemen marched into withering fire that brought down most of their commissioned officers and then their noncommissioned officers. With their leadership in disarray, they fled.

Taylor then ordered his three U.S. Infantry Regiments forward. Pinpoint Seminole fire brought down, he later reported, “every officer, with one exception, as well as most of the non-commissioned officers.”

After a two-and-a-half-hour battle, Colonel Taylor counted 26 U.S. dead and 112 wounded, four Seminole dead, and no prisoners. After his survivors limped back to Fort Gardner, Taylor officially declared victory. “The Indians were driven in every direction,” he erroneously stated in his report. On the strength of that report, Taylor was promoted to General. Decades later, after serving in the Mexican War, he was elected the 12th president of the United States. The real victors, however, were the Indians and the blacks, who held on to their freedom for another two decades.