Asbury Park, New Jersey’s West Side district—predominantly black and housing 40% of the town’s permanent population—was consumed by rioting from July 4 to July 10 in 1970. At the time of the riot, 30% of the population, 17,000 people approximately, were African American. The town’s huge tourist-resort industry brought the population to 80,000 annually and employed a large portion of African Americans. However, over time, jobs were increasingly given to white youth from surrounding areas instead of local black youth, creating an unemployment crisis similar to many other cities at the time. This plus few recreational opportunities and poor housing conditions sparked the violence in 1970.

On July 4, a group of black youth broke windows after a late dance at the West Side Community Center; minor damage and youthful boredom quickly turned to fire bombs and looting. Eventually 180 plus people, including 15 New Jersey state troopers, were injured and 46 people were admitted to the hospital with gun shot wounds by the afternoon of July 8. When asked why so many people were shot, State Police Spokesman Sergeant Joseph Kolbus said that officers had only fired their weapons warnings upwards and the source of so many wounds was unknown. One hundred sixty-seven arrests were made. The entire west side neighborhood, especially the shopping-business section, was destroyed at an estimated cost of $5,600,000.

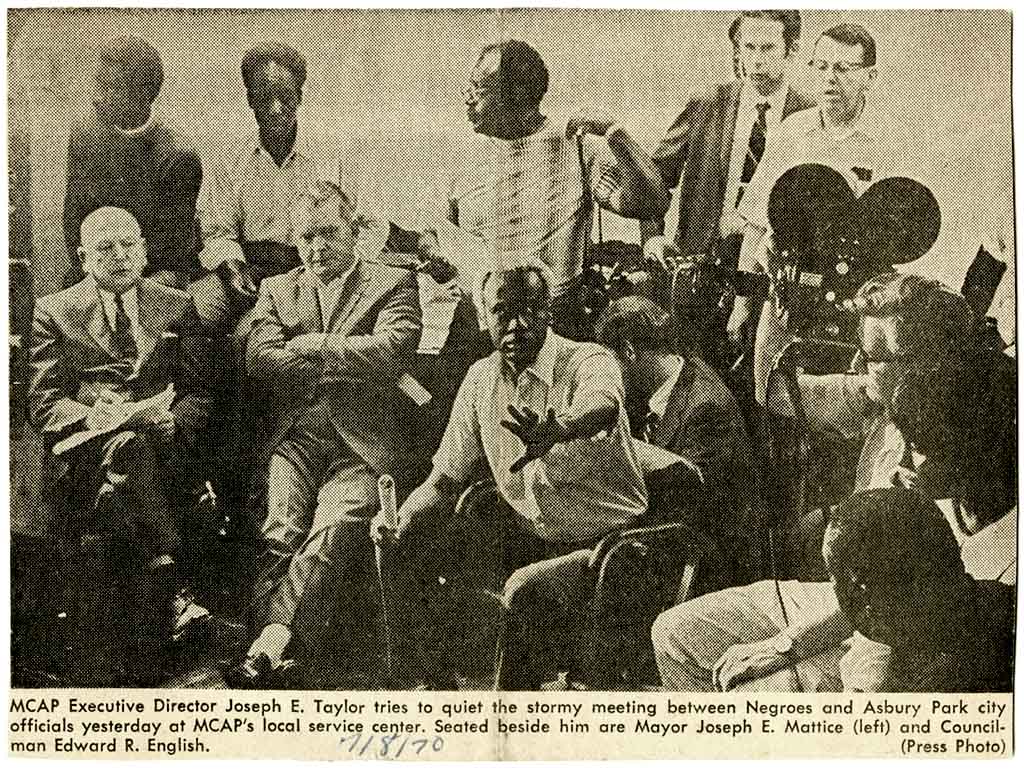

Mayor Joseph F. Mattice, an Asbury lawyer, council member, and judge, ordered a curfew from 8:30 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. starting on July 6, declared a state of emergency, and summoned the New Jersey National Guard. None of these precautions managed to save the properties being destroyed or the people being hurt. By July 7, the damage was so extensive that city officials were ready to compromise, and on that day, a list of twenty demands including employment for black youth and appointment of black people on the Board of Education was sent to the city by African American representatives. On July 8, city officials, representatives from New Jersey’s Governor William Cahill, and local black leaders such as Ermon K. Jones, the local NAACP President, met in a conference. In order to cope with the destruction and displacement occurring during the rioting, the community created “Citizen Peace Patrols,” a group that would walk the streets encouraging people to observe the curfew. They also took in the temporarily homeless.

On July 10, the riot ended. State troopers and National Guardsmen left the West Side, but remained in town. Another conference was called between the Mayor, his council and West Side leaders including Monmouth Community Action Program (MCAP) Executive Director Joseph E. Taylor and West side spokesman, William Hamm, both African American. After the meeting, Governor Cahill requested that President Nixon declare the West side a major disaster area but Nixon refused his request.