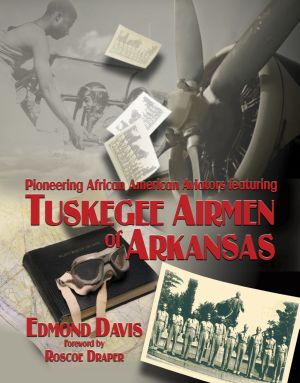

Pioneering African-American Aviators Featuring the Tuskegee Airmen of Arkansas is a study of little known black women and men who participated in the first four decades of U.S. aviation history. The book began originally in 2006 as a biography of Milton Pitts Crenchaw, a native of Little Rock, Arkansas who in 1940 received his pilot’s license and one year later began training black pilots. In 1941, 22-year-old Crenchaw, one of the few black flight instructors in the nation, was recruited to train the cadets who would become the first Tuskegee Airmen. While at Tuskegee Army Air Field from 1941 to 1946, Crenchaw was a Supervising Squadron Commander working under the leadership of Chief Alfred A. Anderson, the ranking black training pilot at Tuskegee. Both he and Anderson along with Shelton Forrest and Charlie Fox trained hundreds of Tuskegee Airmen to fly including the 332ND Fighter Group (the Red Tails).

I first met Milton Crenchaw in February 2005 at Philander Smith College in Little Rock. He told me his story but he also discussed the other men and women who were part of the Tuskegee Airmen program. His account and my own research led me to conclude that while a study of all of his life was warranted, someone also needed to describe these unsung heroes including others like Crenchaw who were from Arkansas.

Over the next two years I interviewed Milton Crenchaw, gathering information on his time as a Tuskegee flight trainer and his role in the history of aviation. Every step of the way Crenchaw exposed me to valuable resources and priceless contacts including other black pioneer Arkansas aviators such as Pickens Black, Jr. and Cornelius Coffey. With financial support in the form of a grant from the Arkansas Black History Commission, a state agency, I was able to travel across the state conducting interviews and gathering additional materials about these little known early black Arkansas aviators.

As my research evolved I encountered challenges. One of the most contentious was the question of who is, and is not, a Tuskegee Airman. One group argues that only those who graduated and saw combat in Europe should legitimately be considered Tuskegee Airmen. Others contend that the designation should apply to all those who graduated from the five year program and can “document” their claim. They say there must be written evidence of an individual’s participation in that program as a cadet who successfully completed training regardless of whether he saw combat in World War II. That evidence should come in the form of any official document from any military department of the United States government or contracted agency during World War II. Persons who fit this description are called Documented Original Tuskegee Airmen or DOTA. Fewer than 1,000 living and deceased pilots fit the DOTA category.

Others claim that numerous “undocumented” individual who for various reasons do not possess clear proof should nonetheless be included in the Tuskegee Airmen designation. A 1973 fire in a St. Louis archive for World War II military personnel, for example, destroyed the records of thousands of airmen, soldiers, and sailors including many of the Tuskegee Airmen and thus eliminated the necessary documentation for many Tuskegee pilots and undermined their claim to membership in this elite group. That accident should not exclude them from the designation, “Tuskegee Airmen” according to their supporters, even if the proof is no longer available.

Still others argue for a more inclusive definition of Tuskegee Airmen contending that the undocumented should include those who entered the program, learned to fly, but never graduated. This included cadets who started the program but did not finish for various reasons (medical, behavioral, social etc.) and were “washed-out,” before the end of their training. They should still be called Tuskegee Airmen, according to this argument, because of the unique and pioneering nature of the program.

Finally, some argue that the undocumented should also include the flight instructor pilots, flight training instructors, aircraft mechanics, medical personnel, officers (white and black) and even the cooks and groundskeepers at the Tuskegee Air Field during World War II. Taken together, this undocumented number totals over 14,000 men and women both civilians and military personnel.

I do embrace the idea that all 14,000 people involved with the Tuskegee military experience should be considered Tuskegee Airmen. The vast majority of them were not pilots nor were they trained to be pilots. My book, however, was developed in part to honor those pilots who did complete the program but who did not witness any aerial combat overseas. Some of those pilots include Granville Coggs, Jerry T. Hodges Jr. Alexander Anderson, and Denny C. Jefferson. It also honors the flight instructors and flight training pilots such as Milton Crenchaw.

Pioneering African-American Aviators also differs from most books on the Tuskegee Airmen by focusing exclusively on the participants from Arkansas. Approximately fifteen pilots and flight instructors were born in Arkansas and trained at Tuskegee between 1941 and 1945. Many of them returned home once World War II was over and contributed to the growth and development of the state. Milton Crenchaw, Alexander Anderson, and Ernest Taylor fit into this category. Fewer people even in Arkansas have heard of Pickens Black Jr. or Cornelius Coffey. In 1933 Pickens Black Jr. was the first African American man certified to fly in Arkansas. Cornelius Coffey, the first African-American to have both a pilot’s and mechanic’s license was from Newport, Arkansas. He is responsible for the Coffey School of Aeronautics in the Chicago, Illinois area and was married to legendary aviatrix Willa Brown.

Pioneering African-American Aviators also looks at other pre-World War II aviation trailblazers beyond Arkansas including Charles Wesley Peters and Emory Conrad Malick. Peters and Malick were both pre World War I aeronauts who began flying 1910 and 1912 respectfully. In 1910 Peters became the first documented African American to fly. Malick in 1912 was the first African American certified to fly with credentials from a flying school in the United States. Malick’s story was recently uncovered by a family member thus exposing his ground breaking aviation exploits to the world indicating again that much of this history remains outside the standard works on American aviation history.

My book also credits the small number of black women who flew before World War II including those who helped train the Tuskegee Airmen. It covers well-known pioneers such as Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman, who because of her training in France, became the first African American woman to gain a pilot’s license anywhere in the world, and Willa Brown, the first licensed black woman pilot in the United States and the first black woman officer in the Civil Air Patrol. It also includes Mildred Hemmons Carter, who had her pilot certificate before her Red Tail Tuskegee Airman husband, Herbert Carter, and Janet Bragg, who was a pioneer helicopter operator.

Finally, this book acknowledges the still living pioneer black aviators including Milton P. Crenchaw, Dr. Granville Coggs, Roscoe Draper, and Jerry T. Hodges. These trailblazers of the skies endured many painful obstacles as they helped change American attitudes toward race and black accomplishment. They raised the bar for all who would follow regardless of race. Milton Crenchaw, for example, was the first Arkansas African American to successfully complete the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) before World War II. After the war he founded and led the flight program at Philander Smith College from 1947 to 1953. Dr. Granville Coggs, after his Tuskegee experience, became a Harvard Trained Radiologist and pioneering breast cancer specialist. A Black Pilots of America (BPA Inc.) chapter in Arkansas was named after Roscoe Draper. Jerry T. Hodges Jr., a pioneering accountant and financial advisor in the Los Angeles metropolitan area for many years became in 2012 one of the last living Arkansas Tuskegee Airmen to be inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame. These men all faced racial, social and class discrimination which they successfully overcame. They helped to push aside widespread myths about what African Americans could accomplish both in the air and on the ground.

Their stories are as much a part of Arkansas history as the story of the Little Rock Nine even if they are not as well known. I hope that with Pioneering African-American Aviators, that their saga including their challenges and their triumphs, will inspire all the people of Arkansas, the United States, and the world.