Founded in Philadelphia in 1869, the Knights of Labor (KOL) was the largest, most important labor union in the 19th century United States. Unlike most unions (and predominantly white institutions) then, the KOL opened its membership to African Americans and women workers. Prior to the KOL, nearly all unions consisted of workers in a specific trade or craft, but craft unions’ emphasis on exclusive membership left them with little power vis-à-vis employers. Also, craft unions generally refused to organize women and people of color. By contrast, a core of the Knights’ philosophy was “solidarity,” that unions must organize all workers, regardless of craft, skill, sex, race, or nationality, as evidenced by its motto, “An injury to one is the concern of all.” The radical ideology of the KOL, admittedly imperfect in practice, also can be seen in its advocacy of cooperative ownership of industry in America.

At first, the union was white- and male-only, but the KOL eventually opened itself to Black and women workers. In addition to its ideology, Knights’ organizers fully understood that, if Black or female workers were excluded, they could be used by employers to undermine unionism. Perhaps as many as 75,000, or about 10% of its peak membership in 1886, were African American along with a comparable number of women.

From Richmond to Raleigh, Galveston to Little Rock, and Kansas City to New York City, Black workers of many trades and places joined the Knights. Since most African Americans lived in the South, most Black KOL members were there. Black workers in the cotton, sugar, timber, and tobacco industries, particularly processing, shipping, and warehousing, belonged. The KOL was not always inclusive: some assemblies, especially in the South, excluded or segregated Black workers. Similarly, Chinese workers were categorically excluded.

The KOL organized in Louisiana’s large sugar industry where Black workers toiled in slave-like conditions. In 1887, about 10,000 Black workers, some of whom belonged to the Knights, struck for three weeks, the largest strike in this industry to date, until 60 strikers were murdered by white paramilitary organizations in the notorious Thibodaux Massacre. No union organized farmworkers for many decades after that massacre.

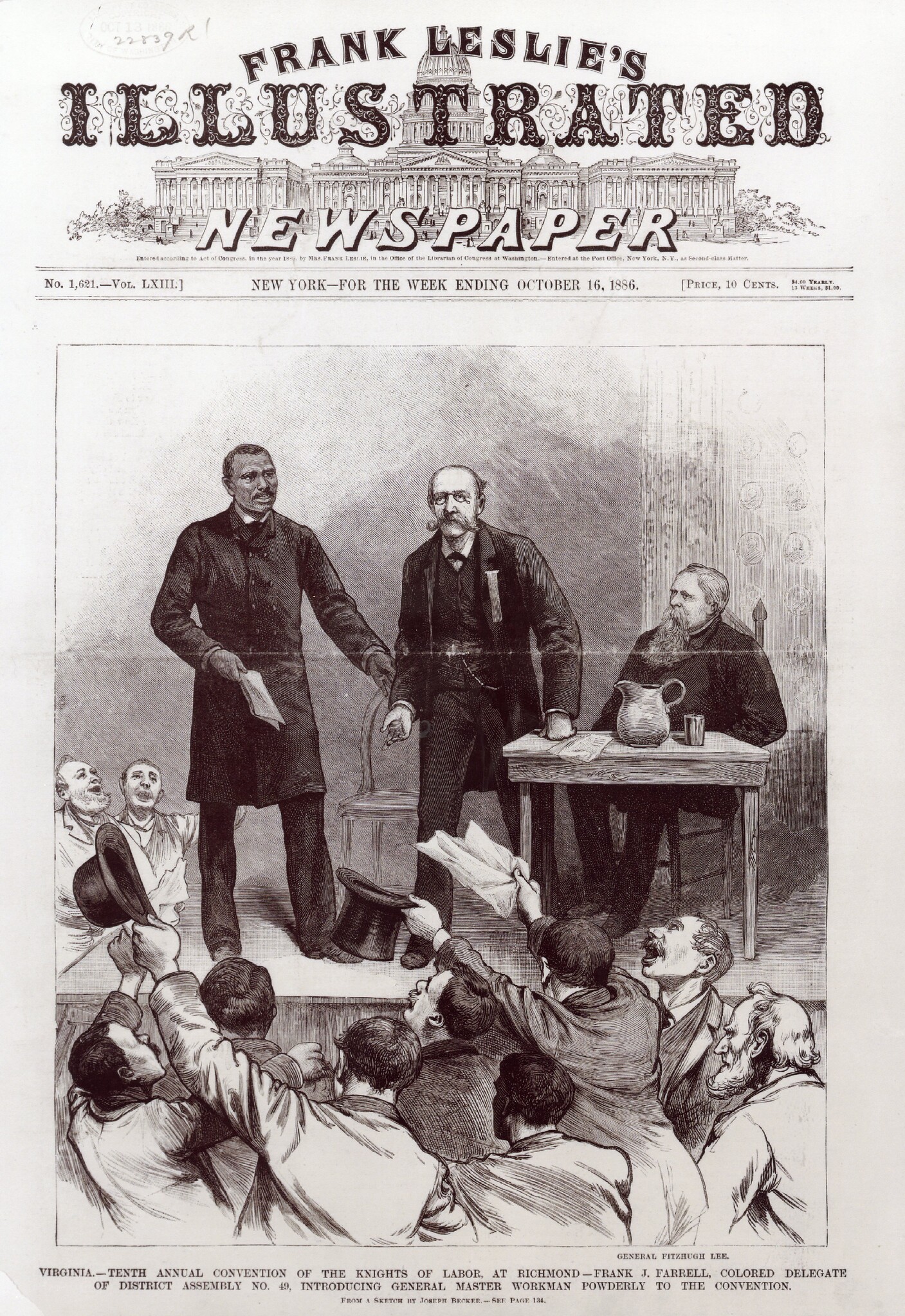

The high-water mark of the Knights’ commitment to racial equality occurred in 1886 at its national convention in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Confederacy and home to thousands of Black Knights. Frank J. Farrell, a militant Black delegate in New York City’s District Assembly 49, was denied admission to a hotel. Rather than accept such discrimination, all delegates from the convention stayed at the Black-owned Harris Hotel. Farrell later addressed the entire convention where he castigated racism in all its forms. The KOL group from NYC also ruffled local racists and received national attention by attending a performance of Hamlet as an integrated body.

In 1886, due to the Haymarket Affair in Chicago, where a bomb killed 16 people, membership plummeted although the KOL had little to do with that event. The KOL lingered on for decades until 1949 and spread to Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. It was not until the Industrial Workers of the World, founded in 1905, opened their doors that another union treated African Americans equally.