The 1964 Paterson, New Jersey uprising lasted from August 11 to 14. The uprising occurred simultaneously with a separate uprising in nearby Elizabeth, New Jersey and both, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), were the consequence of the larger uprisings in New York City (July 18-23), Rochester, New York (July 24-25) and Jersey City, New Jersey (August 2-4).

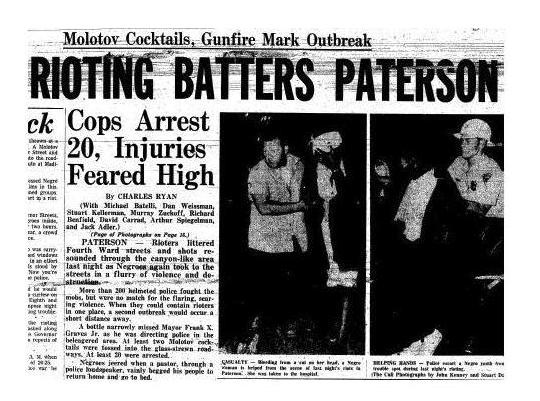

The uprising in Paterson began on the night of August 11 when a group of African American teenagers, returning home from a school dance, began throwing rocks at passing police cars. As the threat of violence increased, Paterson Mayor Frank X. Graves promised to crack down on the uprising and “meet force with force.” Graves had prepared and equipped the Paterson police force for racial violence two months prior to the uprising and had outfitted local officers with riot gear, tear gas, armored personnel carriers, and sawed-off shotguns.

Graves initially ordered police to “shoot to kill” if their lives or the “property of the police” were threatened but rescinded that order to apply only if the officer’s life was in danger. About 200 officers of the 310-man Paterson police force were on the streets throughout the uprising. Paterson’s civil rights officials and community leaders were critical of the city’s obvious preparations for racial trouble and accused Graves of instigating violence rather than attempting to address African American concerns peacefully.

The uprising was centered in a predominantly poor African American neighborhood of Paterson that consisted of mostly “decaying houses” with “rickety porches.” On August 12, members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) traversed the neighborhood asking people to stay home and stay off the streets. They also met with Graves to discuss the needs of the African American community in Paterson which included better housing, rent control, and better recreation facilities. Arthur Jones, a Republican candidate for Third Ward alderman, blamed “fat landlords” who were “leeching off Negroes” for the poor living conditions in African American neighborhoods. Jones was nearly arrested after attempting to intervene between police and African American youths.

Throughout the four days of the uprising, groups of African Americans attacked passing cars with Molotov cocktails, rocks, and other projectiles. City officials estimated that between 300 and 500 people had participated in the rioting in small groups of 20-25 people which precipitated the need for the increased police presence. But the press estimated a lower figure: closer to 100 people in total were involved. This uprising was smaller than the uprisings that preceded it in other cities but it had parallels to those localities. For example, 43 African Americans and three white people were arrested. Fortunately, there were fewer than 10 injuries reported and no deaths.