The 1895 New Orleans Dockworkers Riot was a racially motivated attack on non-union black dockworkers by white dockworkers and their sympathizers. The riot occurred in New Orleans, Louisiana from March 9 through 12, 1895 and marked the end of nearly 15 years of bi-racial union cooperation and union power in New Orleans. The riot also left six black laborers dead and many other wounded.

Throughout the 1880s and into the 1890s, black and white dockworker unions worked together to promote fair working conditions and wages for their workers along the New Orleans waterfront. In 1892, the year of the New Orleans general strike, black and white dockworker unions agreed to share work equally between white and black workers.

Following the economic panic of 1893 and the onset of a national depression, New Orleans commerce suffered tremendously from diminished trade, low cotton prices, smaller crops, and a decline in profits. Economic concerns intensified racial tensions and black dockworkers as white dockworkers began to discuss withdrawing from the equal share agreement.

In 1894, white dockworkers specifically accused black dockworkers of breaking the 1892 agreement by undercutting wages and agreeing to work for less money. By October of 1894, the white dockworkers’ union used that charge to formally expel the black unions from their alliance, terminating the brief bi-racial union association. White dockworkers also dock owners and merchants into hiring white workers only by refusing to work alongside black dockworkers. Rioting first erupted on October 26 after black workers were hired to replace striking white workers on some docks.

In December, 1894, the original 50/50 compromise was re-instated. But racial antagonisms remained as white unions, attempting to maintain their racially dominant position, did not give black dockworkers an equal number of jobs. And black workers, fearful of racial violence and unemployment, and encouraged by Booker T. Washington to abandon their interests in unions and strikes, became increasingly disillusioned. Many of them were now willing to work non-unions jobs both on and away from the docks that paid far less. As a result, an all-black, low-wage enclave developed that competed in a “race to the bottom” bidding war in wages with white unions.

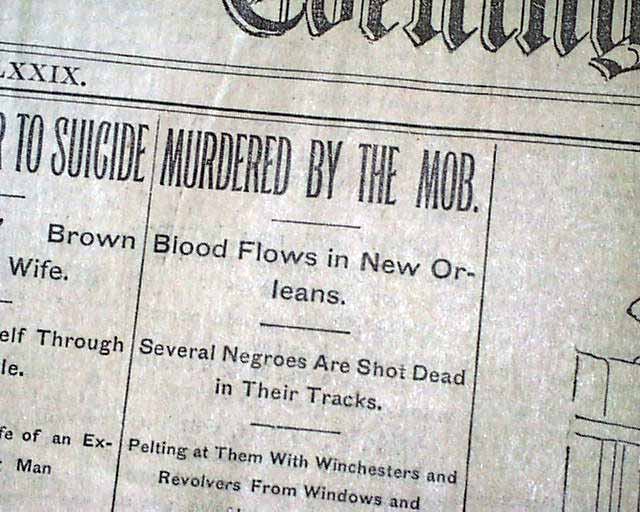

In March 1895, the bidding war between white and black laborers erupted into violence. On March 9, nearly 500 armed white men looted a black dockworkers’ storage house destroying half of their equipment. Two days later two coordinated attacks by several hundred armed white men on black laborers left six black dockworkers dead and many more wounded. On March 13, Louisiana Governor Murphy J. Foster dispatched the state militia to protect commerce and property and allow the black dockworkers to continue working. Although peace prevailed, racial tensions along the New Orleans docks remained strained for years.