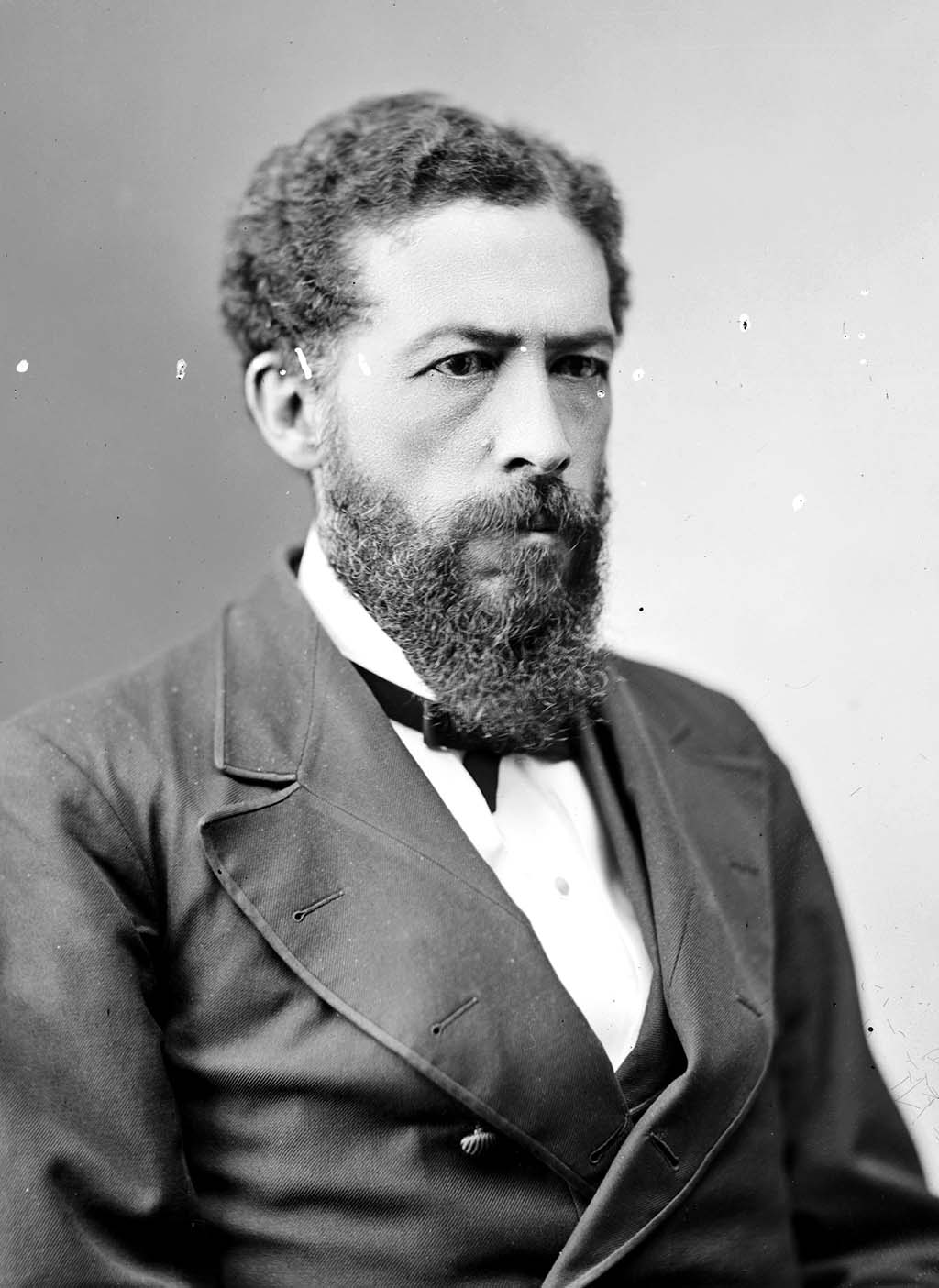

John Mercer Langston, a prominent abolitionist and civil rights activist, was one of the earliest African American officeholders in the United States when in 1855 he was elected town clerk of Brownhelm, Township, Ohio. During the Civil War he recruited soldiers for the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment. In 1888 Langston was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia. In 1874 Langston returns to Oberlin College (from which he graduated in 1849) to give the speech which appears below.

MR. PRESIDENT AND FRIENDS: I thank you for the invitation which brings me before you at this time, to address you upon this most interesting occasion. I am not unmindful of the fact that I stand in the presence of instructors, eminently distinguished for the work which they have done in the cause of truth and humanity. Oberlin was a pioneer in the labor of abolition. It is foremost in the work of bringing about equality of the Negro before the law. Thirty years ago on the first day of last March, it was my good fortune, a boy seeking an education, to see Oberlin for the first time. Here I discovered at once that I breathed a new atmosphere. Though poor, and a colored boy, I found no distinction made against me in your hotel, in your institution of learning, in your family circle. I come here today with a heart full of gratitude to say to you in this public way that I not only thank you for what you did for me individually, but for what you did for the cause whose success makes this day the colored American a citizen sustained in all the rights, privileges and immunities of American citizenship.

As our country advances in civilization, prosperity and happiness, cultivating things which appertain to literature, science and law, may your Oberlin, as in the past, so in all the future, go forward, cultivating a noble, patriotic, Christian leadership. In the name of the Negro, so largely blest and benefited by your institution, I bid you a hearty Godspeed.

Mr. President, within less than a quarter of a century, within the last fifteen years, the colored American has been raised from the condition of four footed beasts and creeping things to the level of enfranchised manhood. Within this period the slave oligarchy of the land has been overthrown, and the nation itself emancipated from its barbarous rule. The compromise measures of 1850, including the Fugitive Slave law, together with the whole body of law enacted in the interest of slavery, then accepted as finalities, and the power of leading political parties pledged to their maintenance have, with those parties, been utterly nullified and destroyed. In their stead we have a purified Constitution and legislation no longer construed and enforced to sanction and support inhumanity and crime, but to sustain and perpetuate the freedom and the rights of us all.

Indeed, two nations have been born in a day. For in the death of slavery, and through the change indicated, the colored American has been spoken into the new life of liberty and law; while new, other and better purposes, aspirations and feelings have possessed and moved the soul of his fellow countrymen. The moral atmosphere of the land is no longer that of slavery and hate; as far as the late slave, even, is concerned, it is largely that of freedom and fraternal appreciation.

Not forgetting the struggle and sacrifice of the people, the matchless courage and endurance of our soldiery, necessary to the salvation of the Government and Union, our freedom and that reconstruction of sentiment and law essential to their support, it is eminently proper that we all leave our ordinary callings this day, to join in cordial commemoration of our emancipation, the triumph of a movement whose comprehensive results profit and bless without discrimination as to color or race.

Hon. Benjamin F. Butler, on the 4th day of July last, in addressing his fellow-citizens of Massachusetts, at Framingham, used the following language, as I conceive, with propriety and truth:

“But another and, it may not be too much to say, greater event has arisen within this generation. The rebellion sought to undo all that ’76 had done, and to dissolve the nation then born, and to set aside the Declaration that all men are created equal, with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. The war that ensued in suppressing this treasonable design, demanded so much greater effort, so much more terrible sacrifice, and has imprinted itself upon the people with so much more sharpness and freshness, that we of the present, and still more they of the coming generation, almost forgetting ’76, will remember ’61 and ’65, and the wrongs inflicted upon our fathers by King George and his ministers will be obliterated by the remembrance of the Proclamation of Emancipation, the assassination of the President, the restoration of the Union, and the reconstruction of the country in one united, and as we fondly trust, never to be dissevered nation.”

The laws of a nation are no more the indices of its public sentiment and its civilization, than of its promise of progress toward the permanent establishment of freedom and equal rights. The histories of the empires of the past, no less than the nations of the present, bear testimony to the truthfulness of this statement. Because this is so, her laws, no less than her literature and science, constitute the glory of a nation, and render her influence lasting:

This is particularly illustrated in the case of Rome, immortalized, certainly, not less by her laws than her letters or her arms. Hence, the sages, the jurists, and the statesmen of all ages, since Justinian, have dwelt with delight and admiration upon the excellences and beauties of Roman jurisprudence. Of the civil law Chancellor Kent eloquently says: “It was created and matured on the banks of the Tiber, by the successive wisdom of Roman statesmen, magistrates and sages; and after governing the greatest people in the ancient world for the space of thirteen or fourteen centuries, and undergoing extraordinary vicissitudes after the fall of the Western Empire, it was revived, ad mired and studied in northern Europe, on account of the variety and excellence of its general principles. It is now taught and obeyed not only in France, Spain, Germany, Holland, and Scotland, but in the islands of the Indian Ocean and on the banks of the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence. So true, it seems, are the words of d’Augesseau, that “the grand destinies of Rome are not yet accomplished; she reigns throughout the world by her reason, after having ceased to reign by her authority.” And the reason through which she here reigns, is the reason of the law.

It is no more interesting to the patriot than to the philanthropist to trace the changes which have been made during the last decade in our legislation and law. Nor is there anything in these changes to cause regret or fear to the wise and sagacious lawyer or statesman. This is particularly true since, in the changes made, we essay no novel experiments in legislation and law, but such as are justified by principles drawn from the fountains of our jurisprudence , the Roman civil and the common law. It has been truthfully stated that the common law has made no distinction on account of race or color. None is now made in England or in any other Christian country of Europe. Nor is there any such distinction made, to my knowledge in the whole body of the Roman civil law.

Among the changes that have been wrought in the law of our country, in the order of importance and dignity, I would mention, first, that slavery abolished, not by State but national enactment, can never again in the history of our country be justified or defended on the ground that it is a municipal institution, the creature of State law. Henceforth, as our emancipation has been decreed by national declaration, our freedom is shielded and protected by the strong arm of national law. Go where we may, now, like the atmosphere about us, law protects us in our locomotion, our utterance, and our pursuit of happiness. And to this leading and fundamental fact of the law the people and the various States of the Union are adjusting themselves with grace and wisdom. It would be difficult to find a sane man in our country who would seriously advocate the abrogation of the 13th amendment to the Constitution.

In our emancipation it is fixed by law that the place where we are born is ipso facto our country; and this gives us a domicile, a home. As in slavery we had no self ownership, nor interest in anything external to ourselves, so we were without country and legal settlement. While slavery existed, even the free colored American was in no better condition; and hence exhortations, prompted in many instances by considerations of philanthropy and good-will, were not infrequently made to him to leave his native land, to seek residence and home elsewhere, in distant and inhospitable regions. These exhortations did not always pass unheeded; for eventually a national organization was formed, having for its sole purpose the transportation to Africa of such colored men as might desire to leave the land of their birth to find settlement in that country. And through the influence of the African Colonization Society not a few, even, of our most energetic, enterprising, industrious and able colored men, not to mention thousands of the humbler class, have been carried abroad.

It may be that, in the providence of God, these persons, self-expatriated, may have been instrumental in building up a respectable and promising government in Liberia, and that those who have supported the Colonization Society have been philanthropically disposed, both as regards the class transported and the native African. It is still true, however, that the emancipated American has hitherto been driven or compelled to consent to expatriation because denied legal home and settlement in the land of his nativity. Expatriation is no longer thus compelled; for it is now settled in the law, with respect to the colored, as well as all other native-born Americans, that the country of his birth, even this beautiful and goodly land, is his country Nothing, therefore, appertaining to it, its rich and inexhaustible resources, its industry and commerce, its education and religion, its law and Government, the glory and perpetuity of its free institutions and Union, can be without lively and permanent interest to him, as to all others who, either by birth or adoption, legitimately claim it as their country.

With emancipation, then, comes also that which is dearer to the true patriot than life itself: country and home. And this doctrine of the law, in the broad and comprehensive application explained, is now accepted without serious objection by leading jurists and statesmen.

The law has also forever determined, and to our advantage, that nativity , without any regard to nationality or complexion, settles, absolutely, the question of citizenship. One can hardly understand how citizenship, predicated upon birth, could have ever found place among the vexed questions of the law; certainly American law. We have only to read, however, the official opinions given by leading and representative American lawyers, in slaveholdinging times, to gain full knowledge to the existence of this fact. According to these opinions our color, race and degradation, all or either, rendered the colored American incapable of being or becoming a citizen of the United States. As early as November 7th, 1821, during the official term of President Monroe, the Hon. William Wirt, of Virginia, then acting as Attorney-General of the United States, in answer to the question propounded by the Secretary of the Treasury, “whether free persons of color are, in Virginia, citizens of the United States within the intent and meaning of the acts regulating foreign and coasting trade, so as to be qualified to command vessels,” replied, saying among other things: “Free Negroes and mulattoes can satisfy the requisitions of age and residence as well as the white man; and if nativity, residence and allegiance combined (without the rights and privileges of a white man) are sufficient to make him a citizen of the United States, in the sense of the Constitution, then free Negroes and mulattoes are eligible to those high offices,” (of President, Senator or Representative,) “and may command the purse and sword of the nation.” After able and elaborate argument to show that nativity in the case of the colored American does not give citizenship, according to the meaning of the Constitution of the United States, Mr. Wirt concludes his opinion in these words: “Upon the whole, I am of the opinion that free persons of color, in Virginia, are not citizens of the United States, within the intent and meaning of the acts regulating foreign and coasting trade, so as to be qualified to command vessels.”

This subject was further discussed in 1843, when the Hon. John C. Spencer, then Secretary of the Treasury, submitted to Hon. H. S. Legare, Attorney-General of the United States, in behalf of the Commissioner of the General Land Office, with request that his opinion be given thereon, “whether a free man of color, in the case presented, can be admitted to the privileges of a pre-emptioner under the act of September 4, 1841.” In answering this question, Mr. Legare held: “It is not necessary in my view of the matter, to discuss the question how far a free man of color may be a citizen in the highest sense of that word that is, one who enjoys in the fullest manner all the jura civitatis under the Constitution of the United States. It is the plain meaning of the act to give the right of pre-emption to all denizens; any foreigner who had filed his declaration of intention to become a citizen is rendered at once capable of holding land.” Continuing, he says: “Now, free people of color are not aliens, they enjoy universally (while there has been no express statutory provision to the contrary) the rights of denizens.” This opinion of the learned Attorney-General, while it admits the free man of color to the privileges of a pre-emptioner under the act mentioned, places him legally in a nondescript condition, erroneously assuming, as we clearly undertake to say, that there are degrees and grades of American citizenship . These opinions accord well with the dicta of the Dred-Scott decision , of which we have lively remembrance. But a change was wrought in the feeling and conviction of our country, as indicated in the election of Abraham Lincoln President of the United States. On the 22nd day of September, 1862, he issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On the 29th day of the following November Salmon P. Chase, then Secretary of the Treasury, propounded to Edward Bates, then Attorney-General, the same question in substance which had been put in 1821 to William Wirt, viz.: “Are colored men citizens of the United States, and therefore competent to command American vessels?” The reasoning and the conclusion reached by Edward Bates were entirely different from that of his predecessor, William Wirt. Nor does Edward Bates leave the colored American in the anomalous condition of a “denizen.” In his masterly and exhaustive opinion, creditable alike to his ability and learning, his patriotism and philanthropy, he maintains that “free men of color, if born in the United States, are citizens of the United States; and, if otherwise qualified, are competent, according to the acts of Congress, to be masters of vessels engaged in the coasting trade. In the course of his argument he says:

1. “In every civilized country the individual is born to duties and rights, the duty of allegiance and the right to protection, and these are correlative obligations, the one the price of the other, and they constitute the all-sufficient bond of union between the individual and his country, and the country he is born in is prima facie his country.

2. “And our Constitution, in speaking of natural-born citizens, uses no affirmative language to make them such, but only recognizes and reaffirms the universal principle, common to all nations and as old as political society, that the people born in the country do constitute the nation, and, as individuals, are natural members of the body politic.

3. “In the United States it is too late to deny the political rights and obligations conferred and imposed by nativity; for our laws do not pretend to create or enact them, but do assume and recognize them as things known to all men, because pre-existent and natural, and, therefore, things of which the laws must take cognizance.

4. “It is strenuously insisted by some that ‘persons of color,’ though born in the country, are not capable of being citizens of the United States. As far as the Constitution is concerned, this is a naked assumption, for the Constitution contains not one word upon the subject.

5. “There are some who, abandoning the untenable objection of color still contend that no person descended from Negroes of the African race can be a citizen of the United States. Here the objection is not color but race only. The Constitution certainly does not forbid it, but is silent about race as it is about color.

6. “But it is said that African Negroes are a degraded race, and that all who are tainted with that degradation are forever disqualified for the functions of citizenship. I can hardly comprehend the thought of the absolute incompatibility of degradation and citizenship; I thought that they often went together.

7. “Our nationality was created and our political government exists by written law, and inasmuch as that law does not exclude per sons of that descent, and as its terms are manifestly broad enough to include them, it follows, inevitably, that such persons born in the country must be citizens unless the fact of African descent be so incompatible with the fact of citizenship that the two cannot exist together.”

When it is recollected that these broad propositions with regard to citizenship predicated upon nativity, and in the case of free colored men, were enunciated prior to the first day of January, 1863, before emancipation be fore even the 13th amendment of the Constitution was adopted; when the law stood precisely as it was, when Wirt and Legare gave their opinions, it must be conceded that Bates was not only thoroughly read in the law but bold and sagacious. For these propositions have all passed, through the 14th amendment, into the Constitution of the United States, and are sustained by a wise and well-defined public judgment. With freedom decreed by law, citizenship sanctioned and sustained before the Law thereby, the duty of allegiance on the one part, and the right of protection on the other recognized and enforced, even if considerations of political necessity had not intervened, the gift of the ballot to the colored American could not have long been delayed. The 15th amendment is the logical and legal consequences of the 13th and 14th amendments of the Constitution. Considerations of political necessity, as indicated, no doubt hastened the adoption of this amendment. But in the progress of legal development in our country, consequent upon the triumph of the abolition movement, its coming was inevitable. And, therefore, as its legal necessity, as well as political, is recognized and admitted, opposition to it has well-nigh disappeared. In deed, so far from there being anything like general and organized opposition to the exercise of political powers by the enfranchised American, the people accept it as a fit and natural fact.

Great as the change has been with regard to the legal status of the colored American, in his freedom, his enfranchisement, and the exercise of political powers, he is not yet given the full exercise and enjoyment of all the rights which appertain by law to American citizenship. Such as are still denied him are withheld on the plea that their recognition would result in social equality, and his demand for them is met by considerations derived from individual and domestic opposition. Such reasoning is no more destitute of logic than law. While I hold that opinion sound which does not accept mere prejudice and caprice instead of the promptings of nature, guided by cultivated taste and wise judgment as the true basis of social recognition; and believing, too, that in a Christian community, social recognition may justly be pronounced a duty, I would not deal in this discussion with matters of society. I would justify the claim of the colored American to complete equality of rights and privileges upon well considered and accepted principles of law.

As showing the condition and treatment of the colored citizens of this country, anterior to the introduction of the Civil Rights Bill, so called, into the United States Senate, by the late Hon. Charles Sumner I ask your attention to the following words from a letter written by him:

“I wish a bill carefully drawn, supplementary to the existing Civil Rights Law, by which all citizens shall be protected in equal rights:

“1. On railroads, steamboats and public conveyances, being public carriers.

“2. At all houses in the nature of ‘inns.’

“3. All licensed houses of public amusement.

“4. At all common schools.

“Can you do this? I would follow as much as possible the language of the existing Civil Rights Law, and make the new bill supplementary.”

It will be seen from this very clear and definite statement of the Senator that in his judgment, in spite of and contrary to common law rules applied in the case, certainly of all others, and recognized as fully settled, the colored citizen was denied those accommodations, facilities, advantages arid privileges, furnished ordinarily by common carriers, inn-keepers, at public places of amusement and common schools; and which are so indispensable to rational and useful enjoyment of life, that without them citizenship itself loses much of its value, and liberty seems little more than a name.

The judicial axiom, omnes homines oequales sunt,” is said to have been given the world by the jurisconsults of the Antonine era. From the Roman, the French people inherited this legal sentiment; and, through the learning, the wisdom and patriotism of Thomas Jefferson and his Revolutionary compatriots, it was made the chief corner-stone of jurisprudence and politics. In considering the injustice done the colored American in denying him common school advantages, on general and equal terms with all others, impartial treatment in the conveyances of common carriers, by sea and land and the enjoyment of the usual accommodations afforded travelers at public inns, and in vindicating his claim to the same, it is well to bear in mind this fundamental and immutable principle upon which the fathers built and in the light of which our law ought to be construed and enforced. This observation has especial significance as regards the obligations and liabilities of common carriers and inn-keepers; for from the civil law we have borrowed those principles largely which have controlling force in respect to these subjects. It is manifest, in view of this statement, that the law with regard to these topics is neither novel nor unsettled; and when the colored American asks its due enforcement in his behalf, he makes no unnatural and strange demand.

Denied, generally, equal school advantages, the colored citizen demands them in the name of that equality of rights and privileges which is the vital element of American law. Equal in freedom, sustained by law; equal m citizenship , defined and supported by the law; equal in the exercise of political powers, regulated and sanctioned by law; by what refinement of reasoning, or tenet of law, can the denial of common school and other educational ad vantages be justified? To answer, that so readeth the statute, is only to drive us back of the letter to the reasonableness, the soul of the law, in the name of which we would, as we do, demand the repeal of that enactment which is not only not law, but contrary to its simplest requirements. It may be true that that which ought to be law is not always so written; but, in this matter, that only ought to remain upon the statute book, to be enforced as to citizens and voters, which is law in the truest and best sense.

Without dwelling upon the advantages of a thorough common school education, I will content myself by offering several considerations against the proscriptive, and in favor of the common school. A common school should be one to which all citizens may send their children, not by favor, but by right. It is established and supported by the Government; its criterion is a public foundation; and one citizen has as rightful claim upon its privileges and advantages as any other. The money set apart to its organization and support, whatever the sources whence it is drawn, whether from taxation or appropriation, having been dedicated to the public use, belongs as much to one as to another citizen; and no principle of law can be adduced to justify any arbitrary classification which excludes the child of any citizen or class of citizens from equal enjoyment of the advantages purchased by such fund, it being the common property of every citizen equally, by reason of its public dedication.

Schools which tend to separate the children of the country in their feelings, aspirations and purposes, which foster and perpetuate sentiments of caste, hatred, and ill-will, which breed a sense of degradation on the one part and of superiority on the other, which beget clannish notions rather than teach and impress an omnipresent and living principle and faith that we are all Americans, in no wise realize our ideal of common schools, while they are contrary to the spirit of our laws and institutions.

Two separate school systems, tolerating discriminations in favor of one class against another, inflating on the one part, degrading on the other; two separate school systems, I say, tolerating such state of feeling and sentiment on the part of the classes instructed respectively in accordance therewith, cannot educate these classes to live harmoniously together, meeting the responsibilities and discharging the duties imposed by a common government in the interest of a common country.

The object of the common school is two-fold. In the first place it should bring to every child, especially the poor child, a reasonable degree of elementary education.

In the second place it should furnish a common education, one similar and equal to all pupils attending it. Thus furnished, our sons enter upon business or professional walks with an equal start in life. Such education the Government owes to all classes of the people.

The obligations and liabilities of the common carrier of passengers can, in no sense, be made dependent upon the nationality or color of those with whom he deals. He may not, according to law, answer his engagements to one class and justify non-performance or neglect as to another by considerations drawn from race. His contract is originally and fundamentally with the entire community, and with all its members he is held to equal and impartial obligation. On this subject the rules of law are definite, clear, and satisfactory. These rules may be stated concisely as follows: It is the duty of the common carrier of passengers to receive all persons applying and who do not refuse to obey any reasonable regulations imposed, who are not guilty of gross and vulgar habits of conduct, whose characters are not doubtful, dissolute or suspicious or unequivocally bad, and whose object in seeking conveyance is not to interfere with the interests or patronage of the carrier so as to make his business less lucrative. And, in the second place, common carriers may not impose upon passengers oppressive and grossly unreasonable orders and regulations. Were there doubt in regard to the obligation of common carriers as indicated, the authorities are abundant and might be quoted at large. Here, however, I need not make quotations. The only question which can arise as between myself and any intelligent lawyer, is as to whether the regulation made by common carriers of passengers generally in this country, by which passengers and colored- ones are separated on steamboats, railroad cars, and stage coaches, greatly to the disadvantage, inconvenience, and dissatisfaction of the latter class, is reasonable.

As to this question, I leave such lawyer to the books and his own conscience. We have advanced so far on this subject, in thought, feeling, and purpose, that the day cannot be distant when there will be found among us no one to justify such regulations by common carriers, and when they will be made to adjust themselves, in their orders and regulations with regard thereto to the rules of the common law. The grievance of the citizen in this particular is neither imaginary nor sentimental. His experience of sadness and pain attests its reality, and the awakening sense of the people generally, as discovered In their expressions, the decisions of several of our courts, and the recent legislation of a few States, shows that this particular discrimination, inequitable as it is illegal, cannot long be tolerated m any section of our country. The law with regard to inn-keepers is not less explicit and rigid They are not allowed to accommodate or refuse to accommodate wayfaring persons according to their own foolish prejudices or the senseless and cruel hatred of their guests.

Their duties are defined in the following language, the very words of the law:

“Inns were allowed for the benefit of travelers, who have certain privileges whilst they are in their journeys, and are in a more peculiar manner protected by law.

“If one who keeps a common inn refuses to receive a traveler as a guest into his house, or to find him victuals or lodging upon his tendering a reasonable price for the same, the inn-keeper is liable to render damages in an action at the suit of the party grieved, and may also be indicted and fined at the suit of the King.

“An inn-keeper is not, if he has suitable room, at liberty to refuse to receive a guest who is ready and able to pay him a suitable compensation. On the contrary, he is bound to receive him, and if, upon false pretences, he refuses, he is liable to an action.”

These are doctrines as old as the common law itself; indeed, older for they come down to us from Galus and Papinian. All discriminations made therefore, by the keepers of public houses in the nature of inns, to the disadvantage of the colored citizen, and contrary to the usual treatment ac corded travelers, is not only wrong morally, but utterly illegal. To this judgment the public mind must soon come. Had I the time, and were it not too great a trespass upon your patience, I should be glad to speak of the injustice and illegality, as well as inhumanity, of our exclusion, in some localities, from jury, public places of learning and amusement, the church and the cemetery. I will only say, however, (and in this statement I claim the instincts, not less than the well-formed judgment of mankind, in our behalf,) that such exclusion at least seems remarkable, and is difficult of defense upon any considerations of humanity, law, or Christianity. Such exclusion is the more remarkable and indefensible since we are fellow-citizens, wielding like political powers, eligible to the same high official positions, responsible to the same degree and in the same manner for the discharge of the duties they impose; interested in the progress and civilization of a common country, and anxious, like all others, that its destiny be glorious and matchless. It is strange, indeed, that the colored American may find place in the Senate, but it is denied access and welcome to the public place of learning, the theatre, the church and the graveyard, upon terms accorded to all others.

But, Mr. President and friends, it ill becomes us to complain; we may not tarry to find fault. The change in public sentiment, the reform in our national legislation and jurisprudence, which we this day commemorate, transcendent and admirable, augurs and guarantees to all American citizens complete equality before the law, in the protection and enjoyment of all those rights and privileges which pertain to manhood, enfranchised and dignified. To us the 13th amendment of our Constitution, abolishing slavery and perpetuating- freedom; the 14th amendment establishing citizenship and prohibiting- the enactment of any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, or which shall deny the equal protection of the laws to all American citizens; and the 15th amendment, which declares that the RIGHT of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, are national utterances which only recognize, but sustain and perpetuate our freedom and rights.

To the colored American, more than to all others, the language of these amendments is not vain. To use the language of the late Hon. Charles Sumner, “within the sphere of their influence no person can be created, no person can be born, with civil or political privileges not enjoyed equally by all his fellow-citizens; nor can any institution be established recognizing distinction of birth. Here is the great charter of every human being, drawing vital breath upon this soil, whatever may be his condition and whoever may be his parents. He may be poor, weak, humble or black; he may be of Caucasian, Jewish, Indian or Ethiopian race; he may be of French, German, English or Irish extraction; but before the Constitution all these distinctions disappear. He is not poor, weak, humble or black; nor is he Caucasian, Jew, Indian or Ethiopian; nor is he French, German, English or Irish- he is a man, the equal of all his fellow-men. He is one of the children of the State, which like an impartial parent, regards all its offspring with an equal care. To some it may justly allot higher duties according to higher capacities; but it welcomes all to its equal hospitable board. The State, imitating the Divine Justice, is no respecter of persons.”

With freedom established in our own country, and equality before the law promised in early Federal, if not State legislation, we may well consider our duty with regard to the abolition of slavery, the establishment of freedom and free institutions upon the American continent, especially in the island of the seas, where slavery is maintained by despotic Spanish rule, and where the people declaring slavery abolished, and appealing to the civilized world for sympathy and justification of their course, have staked all upon “the dread arbitrament of war.” There can be no peace on our continent, there can be no harmony among its people till slavery is everywhere abolished and freedom established and protected by law; the people themselves, making for themselves, and supporting their own government. Every nation, whether its home be an island or upon a continent, if oppressed, ought to have, like our own, a “new birth of freedom,” and its “government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” shall prove at once its strength and support.

Our sympathies especially go out towards the struggling patriots of Cuba. We would see the “Queen of the Antilles” free from Spanish rule; her slaves all freemen, and herself advancing in her freedom, across the way of national greatness and renown. Or if her million and a half inhabitants, with their thousands of rich and fertile fields, are unable to support national independence and unity, let her not look for protection from, or annexation to a country and government despotic and oppressive in its policy. By its proximity to our shores, by the ties of blood which connect its population and ours; by the examples presented in our Revolutionary conflict, when France furnished succor and aid to our struggling but heroic fathers; by the lessons and examples of international law and history; by all the pledges made by our nation in favor of freedom and equal rights, the oppressed and suffering people of Cuba may justly expect, demand our sympathies and support in their struggle for freedom and independence Especially let the colored American realize that where battle is made against despotism and oppression , wherever humanity struggles for national existence and recognition , there his sympathies should be felt, his word and succor inspiriting, encouraging and supporting. To-day let us send our word of sympathy to the struggling thousands of Cuba, among whom, as well as among the people of Porto Rico, we hope soon to see slavery, indeed, abolished, free institutions firmly established, and good order, prosperity and happiness secured. This accomplished, our continent is dedicated to freedom and free institutions, and the nations which compose its population will enjoy sure promise of national greatness and glory. Freedom and free institutions should be as broad as our continent. Among no nation here should there be found any enslaved or oppressed. “Compromises between right and wrong, under pretence of expediency,” should disappear forever; our house should be no longer divided against itself; a new corner-stone should be built into the edifice of our national, continental liberty, and those who “guard and support the structure,” should accept, in all its comprehensiveness, the sentiment that all men are created equal, and that governments are established among men to defend and protect their inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.