The Inkwell was a popular beach for African Americans in Southern California through the middle decades of the Twentieth Century. The beach at Bay Street fanning out a block to the north and south was derogatorily called “The Inkwell” by nearby Anglos in reference to the skin color of the beach-goers. Such names existed for other beaches across the U.S. as well. Nonetheless, African Americans in Southern California, like their counterparts elsewhere, transformed the hateful moniker into a badge of pride.

The Inkwell was originally located at the western end of Pico Boulevard and stretched two city blocks south to Bicknell Street. It was situated near Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church, the first black church in Santa Monica, which also anchored an early black settlement around 4th and Bay Streets in the city. African Americans from throughout Southern California socialized, enjoyed the ocean breezes, and swam at the Inkwell, with less racial harassment than at other area beaches.

Over the decades due to the Inkwell’s unique location, blacks were able to avoid overly hostile discrimination as the area evolved from the edge of public activity to a center of it. Racial discrimination and in particular restrictive covenants prevented African Americans from buying property throughout the urban region, but their community’s presences and agency sustained their oceanfront usage in Santa Monica.

Photo courtesy Rick Blocker

Even the Inkwell was challenged by nearby white homeowners and businessmen. In 1922 the Santa Monica Bay Protective League attempted to purge African Americans from the city’s shoreline by blocking the effort by the Ocean Frontage Syndicate, an African American investment group led by Norman O. Houston and Charles S. Darden, to develop a resort with beach access at the base of Pico Boulevard. Local African American civil rights leaders reflected the ambivalence of the general black population on the continued existence of the Inkwell. While they appreciated the access to the Pacific Ocean that the beach represented, they also wanted an end to all efforts to inhibit their freedom to use all public beaches.

Black beachgoers suffered personal assaults at public beaches north and south of Santa Monica’s borders. In 1927 legal challenges by the Los Angeles branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were made when subterfuge measures of racial restrictions were attempted at Manhattan Beach, a few miles south of Santa Monica. As a result of the NAACP’s actions the California Courts upheld the laws put in place from 1893 to 1923 that provided blacks the rights to use any beach in the state.

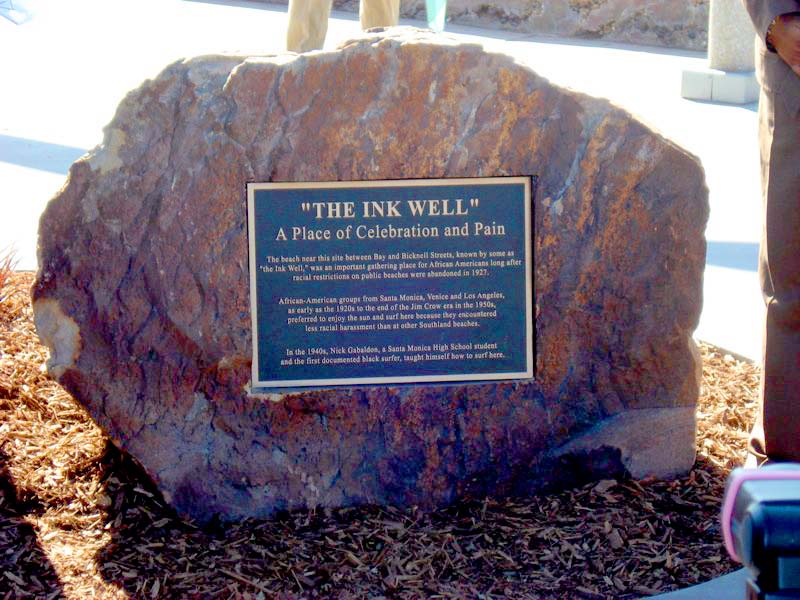

Yet many African Americans continued to return to the Inkwell for sun and surf recreation into the 1960s. On February 7, 2008 the City of Santa Monica officially recognized the “Inkwell” and Nick Gabaldon, the first documented surfer of African/Mexican American descent, with a landmark monument at Bay Street and Oceanfront Walk.