The first Afro-American League (AAL) was established in 1887 before changing its name, two years later, to the National Afro-American League (NAAL). The focus of the league was to obtain full citizenship and equality for African-Americans. Timothy Thomas Fortune, editor of the New York Age and Bishop Alexander Walters of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Washington, D.C. as key figures in the NAAL, sought equal opportunities in voting, civil rights, education, and public accommodations. The organization also sought to end lynchings in the South.

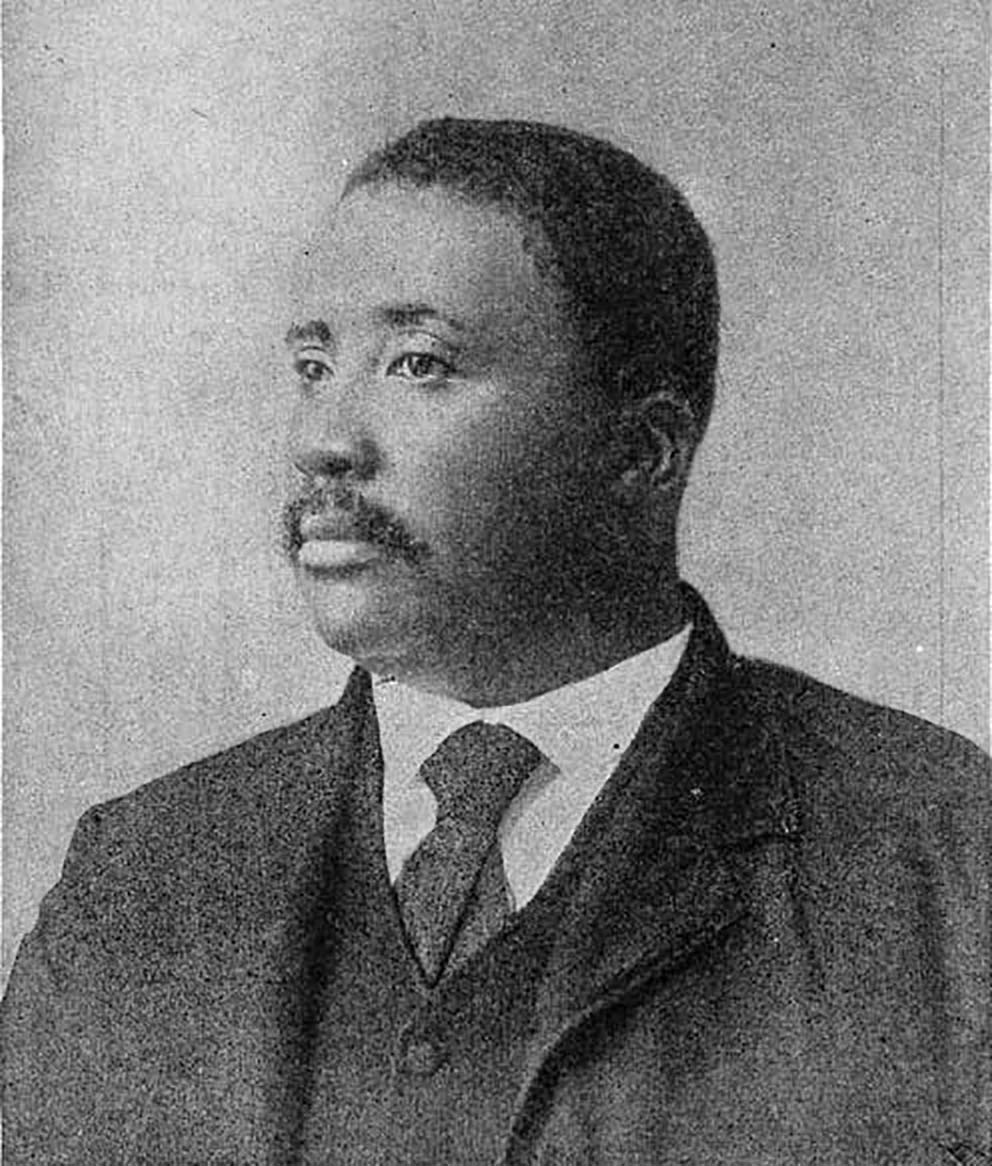

As one of the key figures of the NAAL, Fortune organized the first national meeting in January 1890, where 36-year-old Joseph C. Price, then President of Livingston College in North Carolina, was elected President of the League. During this meeting, the League adopted a constitution that would not accept politicians in order to escape the grasp of the Republic Party’s control. Their main goal would be fighting Jim Crow on legal grounds.

The NAAL initially had several successful lawsuits including a legal victory involving the bar of a New York City hotel where Fortune himself was refused service. However, due to the lack of resources and support from prominent politicians, the organization was unable to continue its efforts and disbanded in 1893. Five years later, the NAAL revived again, but became the Afro American Council (AAC) with Fortune again in a leadership role and Alexander Walters as president.

During the League’s short span, the southern and northern branches created in that time focused on different agendas reflecting the local issues in their areas. Southern branches tried to unite the various local organizations into a single group or at least a coalition to challenge Jim Crow. Northern branches, recognizing that blacks in their region usually had voting and civil rights denied to African Americans in the South, sought to mobilize white public opinion to allow for fuller participation of blacks in the region’s political, economic and cultural life. Neither approach proved particularly effective at that time and the NAAL eventually faded from the scene. The struggle against discrimination in the North and South would eventually be taken up by its successor organizations, the African American Council, the Niagara Movement, and eventually the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).