Benjamin Banneker, free black, farmer, mathematician, and astronomer, was born on November 9, 1731, the son of freed slaves Robert and Mary Bannaky, probably near the Patapsco River southeast of Baltimore, Maryland, where his father owned a small farm. For some years, Banneker seems to have served as an indentured laborer on the Prince George’s County plantation of Mary Welsh, who had dealings with the Bannaky family and in 1773 executed her dead husband’s instructions to release several of her labor force including “Negro Ben, born free age 43.” Walsh was surely not Banneker’s grandmother, as argued by many biographers, but she did leave him a substantial legacy. He then lived alone as a tobacco farmer near the Patapsco River.

By tradition, Banneker received only a brief education from a Quaker schoolmaster. But he showed an early talent for mathematics and construction when, aged 21, he built a model of a striking clock, largely out of wood, that became renowned in his neighborhood. He read widely and recorded his research. His skills drew him into contact with a wealthy white family, the Ellicotts, who had established flour mills and an iron foundry on the outskirts of Baltimore in the mid-1770s.

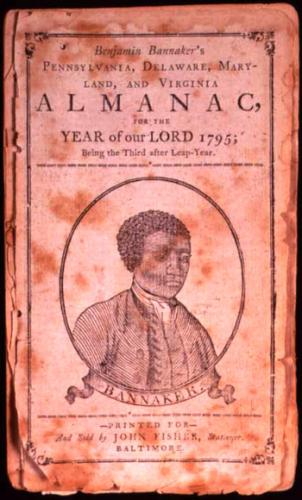

In 1788, George Ellicott, a keen amateur astronomer, lent Banneker books and instruments that enabled him to construct tables predicting the positions of the stars and future solar and lunar eclipses. Three years later, Andrew Ellicott hired Banneker to assist him in surveying the boundaries of the ten-mile square site of the future federal capital of Washington, D.C. In that same year, Banneker won the backing of several Philadelphia, Pennsylvania supporters of the anti-slavery cause to print his work in the popular form of an almanac. Its 1792 publication, introduced by letters pointing out how Banneker’s accomplishments disproved the myth of Negro inferiority, was a considerable success and produced twenty-seven additional editions of “Banneker’s Almanac” over the next five years. Banneker sent a manuscript copy of his work to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, along with a plea against the continuance of black slavery, and received a courteous, if evasive, reply. But Jefferson praised Banneker as “a very respectable mathematician” in forwarding the manuscript to the notice of the French Academy of Sciences.

Banneker continued to live on his farm, in declining health, and died on October 9, 1806. Only fragments of his later writings survive, as most perished in a fire after his death. His life and work have become enshrouded in legend and anecdote. But his achievements ranked him among other American scientists of the time, and they were the more remarkable as the product of patient, lifelong self-education, emerging out of humble origins.