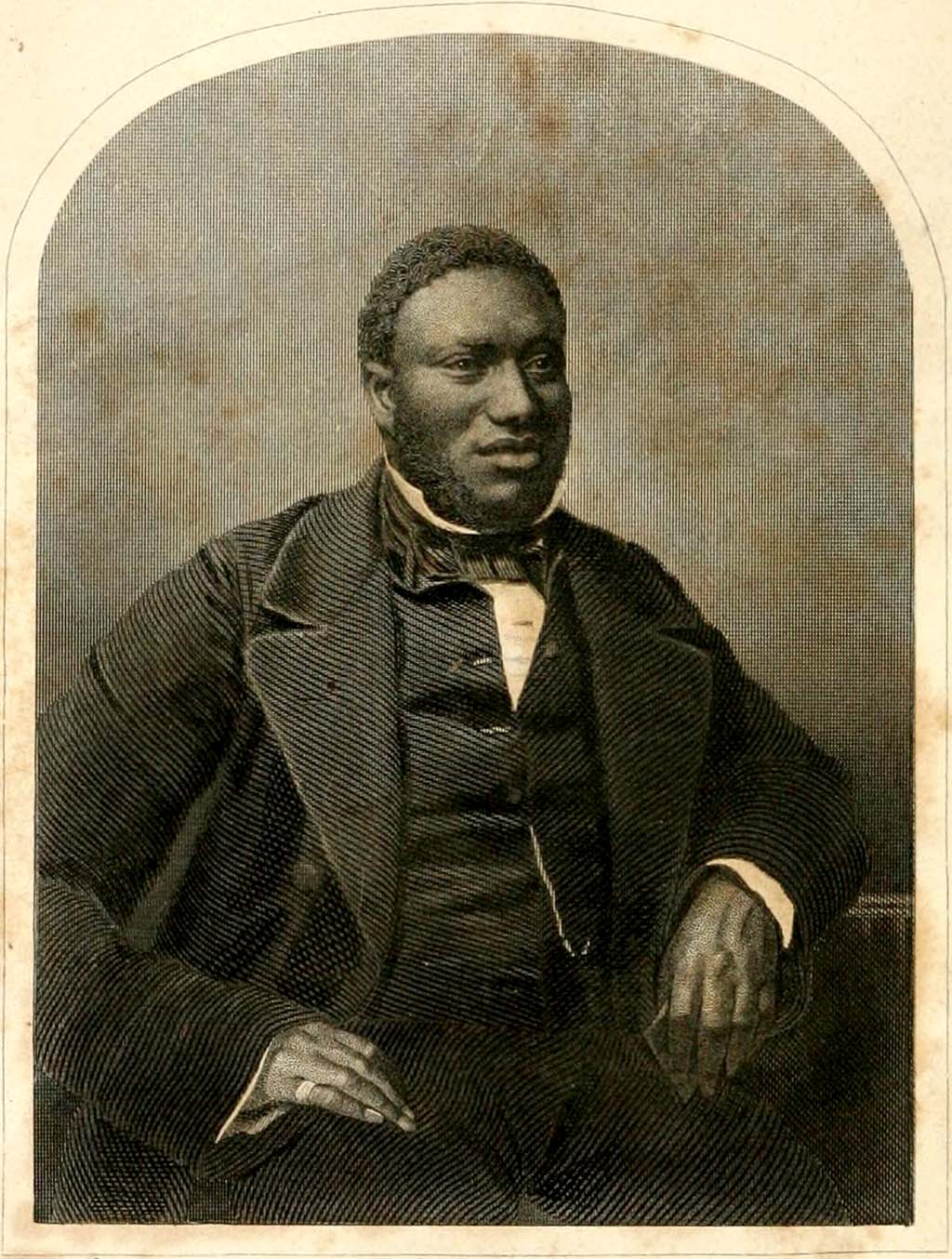

Samuel Ringgold Ward (1817-1864), was one of the most prominent of the anti-slavery speakers in the nation by the 1850s. Born into slavery in Maryland, he escaped with his mother to New Jersey. In 1834 when he was 17 Ward was attacked by a pro-slavery mob in New York and was temporarily jailed. From that point he dedicated himself to the anti-slavery cause. By the 1840s, Ward helped found the Liberty and Free Soil Parties. Ward work variously as a school teacher, newspaper editor and minister. He led two predominately white congregations, a Presbyterian Church in South Butler, New York and a Congregationalist church in Cortland, New York. However after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 he moved to Canada. Ward remained outside the United States for the rest of his life, lecturing in Canada and Europe against slavery. In 1855 he wrote The Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro. Ward retired to Jamaica and died there in 1864. In the speech that appears below, Ward, speaking in Faneuil Hall in Boston, criticizes the then ongoing debate in Congress over the Fugitive Slave Bill.

I am here tonight simply as a guest. You have met here to speak of the sentiments of a Senator of your State whose remarks you have the honor to repudiate. In the course of the remarks the gentleman who preceded me, he has done us the favor to make honorable mention of a Senator of my own State—Wm. H. Seward.

I thank you for this manifestation of approbation of a man who has always stood head and shoulders above his party, and who has never receded from his position on the question of slavery. It was my happiness to receive a letter from him a few days since, in which he said he never would swerve from his position as the friend of freedom.

To be sure, I agree not with Senator Seward in politics, but when an individual stands up for the rights of men against slaveholders, I care not for party distinctions. He is my brother.

We have here much of common cause and interest in this matter. That infamous bill of Mr. Mason, of Virginia, proves itself to be like all other propositions presented by Southern men. It finds just enough of Northern dough-faces who are willing to pledge themselves, if you will pardon the uncouth language of a back-woodsman, to lick up the spittle of the slavocrats, and swear it is delicious.

You of the old Bay State—a State to which many of us are accustomed to look as to our fatherland, just as well look back to England as our mother country—you have a Daniel who has deserted the cause of freedom. We, too, in New York, have a “Daniel who has come to judgment.” Daniel S. Dickinson represents some one, I suppose, in the State of New York; God knows, he doesn’t represent me. I can pledge you that our Daniel will stand cheek by jowl with your Daniel. He was never known to surrender slavery, but always to surrender liberty.

The bill of which you most justly complain, concerning the surrender of fugitive slaves, is to apply alike to your State and to our State, if it shall ever apply at all. But we have come here to make a common oath upon a common altar, that that bill shall never take effect. Honorable Senators may record their names in its behalf, and it may have the sanction of the House of Representatives; but we, the people, who are superior to both Houses and the Executive, too [hear! hear!], we, the people, will never be human bipeds, to howl upon the track of the fugitive slave, even though led by the corrupt Daniel of your State, or the degraded one of ours.

Though there are many attempts to get up compromises—and there is not term which I detest more than this, it is always the term which makes right yield to wrong; it has always been accursed since Eve made the first compromise with the devil. I was saying, sir, that it is somewhat singular, and yet historically true, that whensoever these compromises are proposed, there are men of the North who seem to foresee that Northern men, who think their constituency will not look into these matters, will seek to do more than the South demands. They seek to prove to Northern men that all is right and all is fair; and this is the game Webster is attempting to play.

“Oh,” says Webster, “the will of God has fixed that matter, we will not re-enact the will of God.” Sir, you remember the time in 1841, ’42, ’43 and ’44, when it was said that Texas could never be annexed. The design of such dealing was that you should believe it, and then, when you thought yourselves secure, they would spring the trap upon you. And now it is their wish to seduce you into the belief that slavery never will go there, and then the slaveholders will drive slavery there as fast as possible. I think that this is the most contemptible proposition of the whole, except the support that bill which would attempt to make the whole North the slave catchers of the South.

You will remember that that bill of Mr. Mason says nothing about color. Mr. Phillips, a man whom I always loved, a man who taught me my horn-book on this subject of slavery, when I was a poor boy, has referred to Marshfield. There is a man who sometimes lives in Marshfield, and who has the reputation of having an honorable dark skin. Who knows but that some postmaster may have to sit upon the very gentleman whose character you have been discussing tonight? “What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.” If this bill is to relieve grievances, why not make an application to the immortal Daniel of Marshfield? There is no such thing as complexion mentioned. It is not only true that the colored man of Massachusetts—it is not only true that the fifty thousand colored men of New York may be taken—though I pledge you there is one, whose name is Sam Ward, who will never be taken alive. Not only is it true that the fifty thousand black men in New York may be taken, but any one else also can be captured. My friend Theodore Parker alluded to Ellen Crafts. I had the pleasure of taking tea with her, and accompanied her here to-night. She is far whiter than many who come here slave-catching. This line of distinction is so nice that you cannot tell who is white or black. As Alexander Pope used to say, “White and black soften and blend in so many thousand ways, that it is neither white nor black.”

This is the question, Whether a man has a right to himself and his children, his hopes and his happiness, for this world and the world to come. That is a question which, according to this bill, may be decided by any backwoods postmaster in this State or any other. Oh, this is a monstrous proposition; and I do thank God that if the Slave Power has such demands to make on us, that the proposition has come now—now, that the people know what is being done—now that the public mind is turned toward this subject—now that they are trying to find what is the truth on this subject.

Sir, what must be the moral influence of this speech of Mr. Webster on the minds of young men, lawyers and others, here in the North? They turn their eyes towards Daniel Webster as towards a superior mind, and a legal and constitutional oracle. If they shall catch the spirit of this speech, its influence upon them and upon following generations will be so deeply corrupting that it never can be wiped out or purged.

I am thankful that this, my first entrance into Boston, and my first introduction to Faneuil Hall, gives me the pleasure and privilege of uniting with you in uttering my humble voice against the two Daniels, and of declaring in behalf of our people, that if the fugitive slave is traced to our part of New York State, he shall have the law of Almighty God to protect him, the law which says, “Thou shalt not return to the master the servant that is escaped unto thee, but he shall dwell with thee in they gates, where it liketh him best.” And if our postmasters cannot maintain their constitutional oaths, and cannot live without playing the pander to the slave-hunter, they need not live at all. Such crises as these leave us to the right of Revolution, and if need be, that right we will, at whatever cost, most sacredly maintain.