In the following essay independent historian Robert Fikes explores the eclectic experiences of African Americans in the world’s largest nation in the 19th and 20th Centuries

It was in May 1824 that Nancy Gardner Prince, rescued from a life of poverty and hardship in Massachusetts through a recent marriage, found herself in a most surreal circumstance unlike any previously experienced by an African American in this region of the world. After recently arriving in St, Petersburg, the capital of Imperial Russia, she found herself calmly strolling down magnificent hallways, attentive guards acknowledging her presence. Nancy and her husband passed through doors of the royal palace on their way to keep an appointment with Czar Alexander I, the ruler of the largest nation in the world.

She later recalled in her memoir: “The Emperor Alexander, stood on his throne, in his royal apparel. The throne is . . . covered with scarlet velvet, tasseled with gold; as I entered the Emperor stepped forward with great politeness and condescension, and welcomed me, and asked several questions; he then accompanied us to the Empress Elizabeth; she stood in her dignity, and received me in the same manner the Emperor had.” They presented me with a watch, etc.”

Gifts to the newlyweds were “customary” and befitting those who staffed the imperial court as did Nancy’s husband, Nero Prince, a servant who had sailed to Imperial Russia in 1810 with his American employer and subsequently became an expatriate. She learned to speak the language and spent nine years in St. Petersburg, involved herself in charity and religious work, and establishing two successful businesses.

For other talented and enterprising African Americans who followed, Russia, though a culturally and physically distant and far less traveled destination, offered opportunities not readily available to them elsewhere. Though mostly visitors and temporary residents, these black sojourners nonetheless felt acceptance and appreciated their stay in Russia which they saw as a distant refuge from the daily humiliations that they routinely faced in the United States. Through their travels and experiences half a world away they helped to shape an image of and interest in Russia and the Soviet Union that would inform the views of this land, its people, history and culture for millions of African Americans who would never travel there.

The earliest we hear of Americans of African descent in Russia occurs in the late 1700s when unnamed black sailors, common on American ships sailing abroad then, were mentioned as members of the crews whose vessels docked at Russian ports. In 1809, a manservant known simply as “Nelson” accompanied the family of future U.S. President John Quincy Adams when he traveled to St. Petersburg as U. S. Ambassador. A year later, Adams permitted Nelson to be employed in the service of Czar Nicholas I along with Alexander Gabriel, an AWOL ship’s cook whom the czar impulsively plucked out of a crowd in the Baltic port city of Kronstadt.

An unnamed white American who visited Russia in the mid-1800s commented that many Russians now accustomed to seeing numerous blacks sailors in Russian port cities, assumed that while “all the English-speaking white men were British . . . the Negroes they saw were typical Americans.”

Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge, the first internationally celebrated African American performer, arrived in St. Petersburg in 1857. Leaving a race-obsessed United States for good in 1824, Aldridge captivated audiences across Europe for four decades. Fluent enough to speak in Russian on stage, his 1858 and 1862 tours took him to several important cities and provincial towns, occasioned his friendship with the poet-artist Taras Shevchenko, and was capped with his performance of “King Lear” and “Othello” in St. Petersburg and the awarding of Imperial honors.

In early February 1869 black Civil War veteran and pioneering journalist Captain Thomas Morris Chester from Pennsylvania, on a fundraising tour of Europe, was invited to ride with Czar Alexander II and his staff on a ceremonial review of the Imperial Guard. He later dined with members of the royal family. Unaccustomed to such high public esteem accorded a black American, the black-owned New Orleans Tribune recounted the event in elaborate detail.

The next notable African American black to journey to Russia was explorer Matthew A. Henson who, prior to his exploits in the Arctic with Robert Peary, visited Russian port cities as a cabin boy aboard a merchant ship in the early 1880s. Docking at Murmansk, his ship stood frozen in the harbor all winter and by the time the ice thawed Henson had learned to converse in Russian.

A stalwart campaigner for the Republican Party, in July 1898, Philadelphia-born Richard T. Greener, Harvard’s first black graduate and former dean of Howard University’s law school, accepted a political appointment as U.S. consul to Vladivostok in eastern Siberia. Later, with the support of the Russian government, Greener was reappointed as U.S. commercial agent. Greener also represented British interests Russia after Britain signed a pact with rival Japan. During his years abroad in the service of his country Greener reported on demographic shifts in the Russian population and observed the completion of the Trans-Siberian railway and the Russo-Japanese War. Though his good work was cited in the American press, he was wrongly charged with incompetence and recalled from his post in 1905.

The wildly successful entertainment impresario Frederick Bruce Thomas, the son of ex-slaves, escaped with his family from the Mississippi Delta in 1890 and in 1894 ventured to Europe seeking opportunities he was not allowed in America. He had the good fortune to be employed by an aristocrat who took him to Moscow in 1899 where he worked his way up from waiter to owner of “Yar,” the most fashionable restaurant in the city. By 1911 Thomas had partnered with two Russians to purchase the Aquarium entertainment complex within which he established a successful variety theater called Maxim. White American tourists in Moscow wrote home telling of their amazement at spotting this expensively attired African American, who had acquired Russian citizenship and changed his name to Fyodor Fyodorovich Tomas, in such an unexpected place. Life was grand for Fyodor Tomas until the Russian Revolution erupted in 1917 and this prominent bourgeois capitalist was forced to flee leaving behind once valuable properties, including his villa in Odessa. Thomas died penniless in Istanbul at age 46.

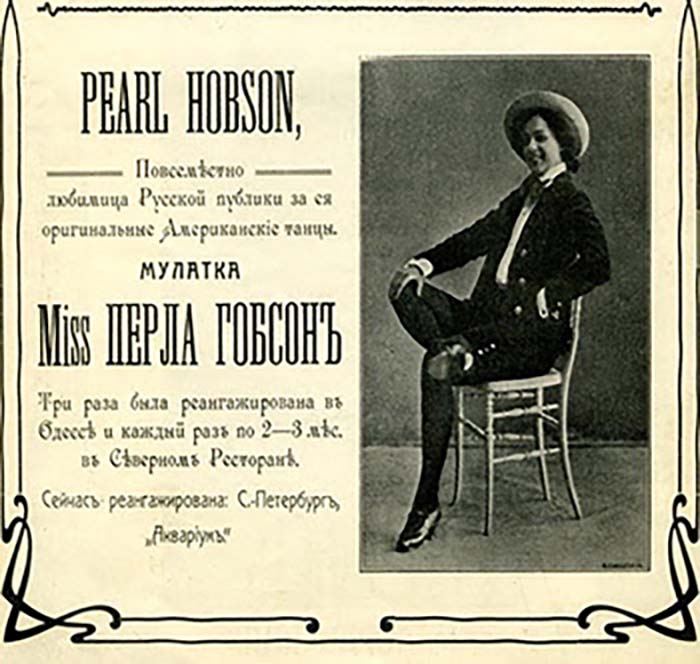

Undoubtedly, Thomas was aware of the sudden appearance in 1904 of a number of African American professionals in Russia’s bustling western cities. These were mostly entertainers in touring troupes who profited from the vogue of black popular culture in Europe during the first three decades of the 20th Century. Among them were the Darktown Entertainers, Black Diamonds, and Sam Wooding and his Chocolate Kiddies. Pearl Hobson was part of this group, arriving in Russia in 1904 and becoming something of a local sensation in Moscow and St. Petersburg by 1909. Hobson lived in Russia until 1916. Other entertainers learned the Russian language and became permanent residents.

Prominent among the non-entertainers who arrived in this period were jockey Jimmy Winkfield who between 1903 and 1914 won several banner races in Russia including Moscow Derby twice, the Russian Derby thrice; and married Russian baroness, Alexandra Yalovicina. Jamaican–born Robert Josias Morgan who had served as deacon in Episcopal Church parishes in five Atlantic coast and Southern states, left for Russia in 1904 where he visited monasteries in key cities, and eventually became the first black Eastern Orthodox priest in 1907. The coming of World War I ultimately forced boxer Jack Johnson to cut short his stay in Moscow in 1914.

World War I devastated Imperial Russia and led to the 1917 Russian Revolution. By 1919 the Bolsheviks (Communists) gain effective control of the country. Dedicated to economically and politically transforming the nation and leading a worldwide revolution, the new Communist leadership under Joseph Stalin in the early 1920s, declared that African Americans would be in the vanguard of that revolution in the United States. They also declared that Communists everywhere would fight to eradicate racism as well as capitalism and imperialism.

For the first time in world history, the leadership of a powerful European nation declared as its priority the elimination of racial discrimination around the world. Understandably African Americans would take a particular interest in developments in the nascent Soviet Union now officially known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). By the by the early 1920s a trickle of African Americans departed for Soviet Russia in two distinct groups: those attracted to and desiring to help fulfill communism’s promise of racial and social equality, and assorted artists and intellectuals lured by a welcoming totalitarian bureaucracy wanting to showcase its self-proclaimed accomplishment of anti-racism and international brotherhood in stark contrast to the United States. Harry Haywood, Claude McKay, James W. Ford, and Otto Huiswood were among those who arrived during the 1920s.

The trickle of black leftists in the Soviet Union increased considerably in the early 1930s. Some black Communist Party members including Detroit, Michigan factory worker Robert N. Robinson, New York attorney William L Patterson, New York schoolteacher Williana Burroughs, and Mississippi-born agricultural specialist Oliver Golden, all arrived at different times and saw themselves playing different roles in building the new Socialist utopia. War correspondent Homer Smith, a former postal worker from Minneapolis, Minnesota survived reporting German military maneuvers on the Eastern Front in World War I. Some of these individuals stayed for several years while others never returned to the United States. Union organizer Lovett Fort Whiteman, a Tuskegee Institute graduate from Dallas, Texas, who emigrated to the Soviet Union from New York in 1930 to help build the new society, was a victim of Stalin’s Great Purge. He died horribly in the infamous Kolyma Gulag in Siberia in 1930.

African American artists and intellectuals were less inclined to extend their time in the “worker’s paradise” and did not involve themselves in treacherous, sometimes deadly internecine Communist Party politics. Poet Claude McKay, who met Leon Trotsky at a Comintern conference in 1922 summarized the event for African American readers in his article in the NAACP’s The Crisis. Black intellectual and political activist W.E.B. Du Bois took the first of several trips to the Soviet Union in 1926. Over the years, when back in the United States, he both praised and criticized Soviet leaders before finally joining the Communist Party in 1961 and then emigrating to Ghana. Concert tenor Roland Hayes was warmly received in 1928 in Moscow, Kiev, and Leningrad. Contralto Marian Anderson performed in the Soviet Republics of Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, and Azerbaijan in 1935.

Lolita Marksiti in Moscow, ca. 1930

Encouraged by Soviet authorities, in 1932 a distinguished group of 23 black actors and writers including Henry Lee Moon, Ted Poston, Wayland Rudd, Langston Hughes, and Dorothy West traveled to Moscow intending to make a film portraying racism in the United States. The project soon collapsed but was nonetheless an enriching cultural experience for novelists Hughes and West who extended their stay to a year. Hughes traveled across the USSR spending some time in Soviet Central Asia before moving on to China. Wayland Rudd stayed in the USSR and married a Russian woman, Lolita Marksiti.

Paul Robeson, both an artist and political activist, would have the greatest affinity for and influence in the Soviet Union. The New Jersey-born actor, singer (and attorney) first visited the Soviet Union in 1934. Robeson studied Russian and arranged with Soviet officials for his son, Paul Robeson Jr., to attend school in Moscow. Between 1934 and 1963 Robeson visited the Soviet Union on four occasions, performing in concert halls and on factory floors. By the early 1950s when Cold War pressures forced most earlier Soviet supporters to denounce the Communist state, Robeson remained loyal to the nation, a loyalty that promoted the U.S. State Department to rescind his passport and entertainment moguls to curtail his professional career.

African Americans became notably less enthusiastic about the Soviet Union after the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact ended the “Popular Front” of Communists and non-Communists who had been united by their opposition to fascism. Even when the U.S. and the U.S.S.R became allied again against the Axis nations during World War II, most African Americans (Paul Robeson excepted) lost their enthusiasm for the Soviet experiment.

By the time of the Cold War in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were now open rivals and enemies, the idealistic notion of the USSR as refuge and prototype of the antiracist state had lost its hold on the black intelligentsia. Disillusionment gave way to disinterested observation from afar.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s the most prominent African American travelers to the Soviet Union were the handful of black entertainers and artists sent through the auspices of the U.S. State Department. These entertainers including neoclassical composer Ulysses Kay in 1958, painter Avel DeKnight in 1961, jazz pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines in 1966, and the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1971 were ostensibly there to promote African American art and music as representative of American “cultural” democracy. In fact these artists and entertainers were witting or unwitting agents in the ongoing propaganda war between the two nations. Black artists by their presence suggested that American racism was not as virulent as the official Soviet government claims.

By the 1970s a new generation of African Americans traveled to the Soviet Union. These sojourners were not sponsored by the United States government and in some instances they were opposed to that government. In 1979 radical political activist Angela Davis won the Lenin Peace Prize, traveling to Moscow to receive the honor. American conductor James Frazier led the revered Leningrad Philharmonic in concert in 1971. Playwright-novelist Alice Childress toured the USSR with members of the Harlem Writers Guild in 1971. Artist Elton Fax illustrated and published a book in 1974 recalling, among other, his recent travels in the central Asian regions of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s the Dance Theatre of Harlem was applauded in Leningrad, artists Paul Goodnight helped direct a mural project in Soviet Armenia, and Kehinde Wiley painted in a forest outside Leningrad.

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ended on December 25, 1991 with resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as the last Premier of the Soviet Union. In its place now stood twelve new nations, the largest and most powerful of which is the Russian Federation. The idea of a nation dominated by an ideology dedicated to eradicating racial discrimination died as well with the USSR. While some African Americans no longer looked to Russia with hope that it would challenge American racism, others were relieved that with the end of the Cold War, the threat of world nuclear annihilation was significantly diminished.

Fortunately some black Americans would continue to be involved in cultural exchange. In 2005 the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater performed in St. Petersburg. In 2012 Maestro Marlon Daniel conducted the Tatarstan State (former Soviet Republic) Symphony Orchestra for a performance of William Grant Still’s “Afro-American Symphony.” That same year opera stars Lawrence Brownlee and Jessye Norman sang in St. Petersburg and Moscow. In 2006 former New York fashion maven Andre Talley became editor-at-large of Numero Russia. He was the first American to manage a Russian magazine. Today a number of African American scholars focus on Russian history and culture including Kimberly St. Julian who learned Russian at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and Oxford University in England, was award a research fellowship to study in Ukraine, and in 2014 received an M.A. from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Few European nations have held such a powerful place in the African American imagination. In the 19th Century a handful of black Americans found imperial autocratic Russia to be a haven from the racial discrimination so common in the “democratic” United States. For most of the 20th Century, the anti-racist ideology of the Soviet Union held an attraction even when the actual treatment of individual African Americans seemed far removed from the ideal of Russian racial equality. By 1991 the Soviet Union disintegrated and in its place are fifteen nations all of which are grappling with ethnic and racial conflicts within their boundaries. It remains to be seen if Russia of the 21st Century will ever capture the African American imagination as it has in the past.