Today the phrase “Uncle Tom” evokes a powerfully negative image in American society. It depicts a weak, subservient, cringing black man who betrays his race and its struggle for liberation. David Reynolds, an English professor in the Graduate School of the City University of New York (CUNY), returns to the original “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to revel that the character Harriet Beecher Stowe described in her 1852 novel is wholly opposite of the caricature we now imagine. His article explores how Stowe’s Uncle Tom evolved into our contemporary image of Uncle Tom.

The novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, born 200 years ago, was an unlikely fomenter of wars. Diminutive and dreamy-eyed, she was a harried housewife with six children who suffered various obscure illnesses, worsened by her persistent hypochondria. And yet, driven by a passionate hatred of slavery, she found time to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became the most influential novel in American history and a catalyst for radical change both at home and abroad.

Today, of course, the book has a decidedly different reputation, thanks to the popular image of its titular character, Uncle Tom — a name that has become a byword for a spineless sell-out, a black man who betrays his race.

But this view is egregiously inaccurate: Uncle Tom was physically strong and morally courageous, an inspiration for blacks and other oppressed people worldwide. In other words, Uncle Tom was anything but an “Uncle Tom.”

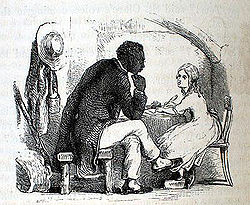

Stowe describes Tom as “a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man” with a “self-respecting and dignified” look that indicates “grave and steady good sense.” A man around forty with a wife and three children, he is notable precisely because he does not betray fellow enslaved blacks. He turns down an opportunity to escape from his Kentucky plantation because he doesn’t want to put his fellow slaves in danger of being sold or punished. Later on, he endures a terrible whipping at the hands of the cruel slaveowner Simon Legree because he refuses to reveal where two enslaved women are hiding. We are told that Tom “felt strong in God to meet death, rather than betray the helpless.” Legree regards Tom as a brash troublemaker who is despicable because he is unflinching: “Had not this man braved him,–steadily, powerfully, resistlessly,–ever since he bought him?” After the Civil War a group of ex-slaves to whom the novel was read aloud declared that few enslaved blacks would have dared to resist their master as determinedly as Tom does.

Moreover, in a day when blacks were widely regarded by whites as subhuman, lustful, or comically irresponsible, Uncle Tom’s Cabin demonstrated that they were capable of the full range of feelings—loyalty, friendship, sorrow, pity, and religious devotion. On every page, Stowe made a crystal-clear point: blacks were human, and to enslave them was evil.

That’s why in the mid-nineteenth century Southerners savagely attacked “Uncle Tom Cabin” as a dangerously radical book. A Southern political cartoon depicted Stowe in hell, surrounded by demons and holding a book titled Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I Love the Blacks. Previously, Southerners had thought it unnecessary to write lengthy defenses of slavery, which was seen as a natural part of the American system. But Uncle Tom’s Cabin made its point so powerfully and with such popular success—it sold over 300,000 copies in America and around 1.5 million abroad in a year–that it provoked numerous attacks in Southern poems, reviews, articles, and books. Thirty novels were written in reply to “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” In these so-called anti-Tom novels, slavery was presented as a wonderful institution, sanctioned by the Bible and by the laws of the land, that provided ignorant African savages with shelter, food, and religious instruction.

Meanwhile, Stowe’s novel greatly strengthened antislavery sentiment in the North. For the first time, Northerners felt the horrors of slavery on their nerve endings. Many antislavery reformers jumped on the Uncle Tom juggernaut. Previously, the antislavery movement had been divided between small, conflicting groups that were widely unpopular. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a force for unity and cohesion among these fragmented groups. Stowe was overjoyed by the embrace of her novel by different antislavery factions. She said, “The fact that the wildest and extremest abolitionists have united with the coldest conservatives to welcome and advance my book is a thing that I have never ceased to wonder at.”

The impact of Stowe’s novel was amplified by a powerful cultural phenomenon known as “Tomitudes”–representations of the novel in all popular mediums: puzzles, card games, dolls, chinaware, and so on. The most influential tie-ins were plays based on the novel, the first of which appeared in 1852, just a few months after the publication of the novel. Far more people saw the play Uncle Tom’s Cabin than read the novel. Pathos, thrills, music, impressive backdrops: all the crowd-pleasing elements were there in the play, which appeared throughout the North and everywhere made converts to the antislavery cause. The most surprising converts were Northern working-class types who had previously been known for their violence against abolitionists or blacks. It was unprecedented to see white working-class people cheering for fugitive slaves, hissing at a cruel slaveowner, and weeping over the death of an enslaved black man.

The novel had a key role in the political reshuffling that lay behind the rise of the antislavery Republican Party. As the novel’s stature grew, it gave strong impetus to antislavery politics. In 1856, one journalist wrote:

Much Anti-Slavery truth, heretofore discarded by people as fanatical, is now received and read by all. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, thundering along the pathway of reform, is doing a magnificent work on the public mind. Wherever it goes, prejudice is disarmed, opposition is removed, and the hearts of all are touched with a new and strange feeling, to which they before were strangers.

Stowe’s novel was often mentioned in political speeches, like one on the House floor by the Ohio congressman Joshua Giddings, who declared, “A lady with her pen has done more for the cause of freedom, during the last year, than any savant, statesman, or politician of our land. The inimitable work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is now carrying truth to the minds of millions, who, up to this time, have been deaf cries of the down-trodden.”

Thus the novel crystallized the debate over slavery and intensified the tensions that led to the Civil War. By the eve of the war, as one commentator of the day noted, the novel “had given birth to a horror against slavery in the Northern mind which all the politicians could never have created ” and “did more than all else to array the North and South in compact masses against each other.”

And the novel’s influence lasted long after the Civil War. In 1882, the ex-slave Frederick Douglass affirmed that no one had done more for the progress of African Americans than Stowe. As the black intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois later wrote, “Thus to a frail overburdened Yankee woman with a steadfast moral purpose we Americans, black and white, owe gratitude for the freedom and union that exist today in the United States of America.”

The book stoked fires overseas, too. In Russia it influenced the 1861 emancipation of the serfs and later inspired the Bolshevik leader Nikolai Lenin, who recalled it as his favorite book in childhood. It was the first American novel to be translated and published in China, and it fueled antislavery causes in Cuba and Brazil.

At the heart of the book’s progressive appeal was the sturdy, proud Uncle Tom himself. Unfortunately, Tom was grossly misrepresented in post-Civil War stage versions of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that catered to the tastes of the Jim Crow era. By the 1890s, there were hundreds of acting troupes — so-called Tommers — that fanned out across North America, putting on “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in every town, hamlet and city. Some troupes even toured internationally, performing as far away as Australia and India. The play remained popular up to the 1950s and still appears occasionally, as in Alex Roe’s staging in fall 2010 at the Metropolitan Playhouse in New York City’s East Village.

In many of the plays, Stowe’s revolutionary themes were drowned in sentimentality and spectacle. Uncle Tom was often presented as a stooped, obedient old fool, the model image of a submissive black man preferred by post-Reconstruction, pre-civil rights America.

It was this Uncle Tom, weakened both physically and spiritually, who became a synonym for the racial sellout by the mid-twentieth century. Black musicians, sports figures, even establishment civil rights leaders were all tarred with the Uncle Tom label, often by younger, more radical activists, as a way of demeaning them in the eyes of the African-American community.

But it doesn’t have to be that way; Uncle Tom should once again be a positive symbol for African-American progress. After all, many people who over the years were derided as Uncle Toms — Jackie Robinson, Louis Armstrong and Willie Mays, to name a few — are now seen as brave racial pioneers.

Indeed, during the civil rights era it was those who most closely resembled Uncle Tom — Stowe’s Tom, not the sheepish one of popular myth — who proved most effective in promoting progress. Rosa Parks didn’t mind the Uncle Tom label, since she believed that great change could result from nonviolent moral protest. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., though often called an Uncle Tom, also stuck to principled nonviolence.

A quiet woman who refused to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, a pacifist minister who told America about his dream of a more egalitarian nation. Their form of protest was just as active as Tom’s, and just as strong. Both Stowe and Tom deserve our reconsideration — and our respect.