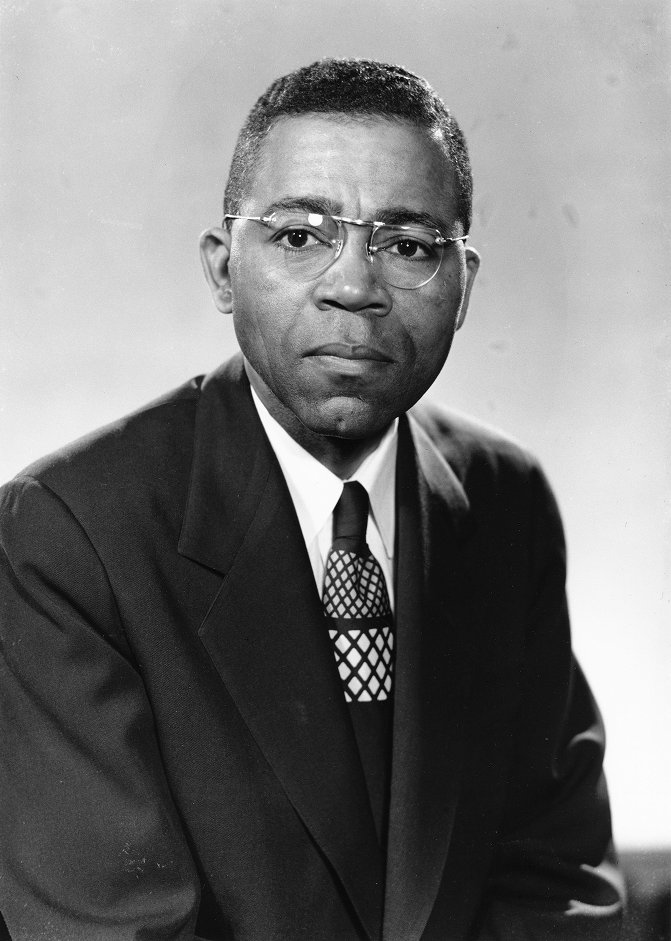

In the following article drawn from his book, Black Philosopher, White Academy: The Career of William Fontaine, University of Pennsylvania historian Bruce Kuklick introduces us to the world of philosopher William Fontaine, one of the few African American faculty members at an Ivy League institution in the late 1940s and the only black person then on the University of Pennsylvania faculty.

In the spring of 1947 the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia appointed William Fontaine to a one-year visiting lectureship in its Department of Philosophy for the academic year 1947-48. The black man at once took leave of Morgan State College, an African American school in Maryland that had hired him after World War II as Professor and Chairman of its Philosophy Department. Pennsylvania repeated the arrangement for 1948-49. As part of his entrée into the white academic world, in the summer of 1948, Fontaine applied to take a place in the American Philosophical Association, a prestigious scholarly organization that one could not merely join with a check. The APA traditionally held its annual conventions over the Christmas holidays of the collegiate world, and at the end of 1948 Fontaine made plans to attend the gathering of the premier Eastern Division of the Association. The University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, a few hours to the south, would host the meeting where the APA would formally Fontaine accept into full membership.

Fontaine got a ride down and back with his colleague at Pennsylvania, Nelson Goodman, who was to become known as one of the most formidable professional American philosophers in the fifty years after World War II. Morton White, regarded as an influential student of American thought, also traveled in the car. He taught at Pennsylvania for a few years in the late 1940s and later went to Harvard University and then to a lifetime appointment at the Institute of Advanced Study located near Princeton University. On the way back, Goodman filled his car by giving a lift to the visiting Oxford philosopher A. J. Ayer. Intellectuals knew him as the most famous thinker in the English-speaking world, the aged Bertrand Russell aside. Knowledgeable people interested in the history of British Empiricism spoke of its great tradition: John Locke, David Hume, John Stuart Mill, Russell–and Ayer.

All of Fontaine’s traveling companions were assimilationist Jews, demanding of acceptance in their Christian civilization. They despised prejudice and had a vivid sense of what they saw as the chief issue of World War Two, bigotry based on racial stereotypes. Personally fastidious and consistently formally clothed, the white thinkers seemed to challenge the social order to find fault with their accomplishments, intelligence, or culture. Fontaine too unfailingly dressed in a suit to signify that he was no ordinary black man. On their arrival in Charlottesville, however, the philosophers crossed the tracks and made their way into the “Nigra’ section” of town — the South was of course segregated and Fontaine would not be staying at the official APA hotel. The group found his black lodging house, and the elegantly attired men of mind climbed out of the car and dusted off their garments. The white members of the party helped Fontaine with his luggage, and clumsily assisted him on the sidewalk. They saw him into the establishment, professed that they would meet up with him later, and piled back into the automobile. What did they say to one another as they proceeded to the convention? Morton White remembered the end of the trip as “chilling.” In his memoirs Ayer too recalled the incident, which prompted a criticism of American racial practices.

The next year, to their credit, these men and others passed a resolution not to hold APA meetings in segregated cities. But I am more interested in Fontaine’s response. What kind of impact did experiences of this sort have on him? How did he respond to this shaming in front of men such as Goodman, White, and Ayer? Did he talk about its significance to other African Americans? What did it mean to him, a few hours later, to wait outside the APA’s hotel until some white philosopher came to the entrance and told the doorman–was he black? — that Fontaine belonged with the philosophers but of course was not staying at the headquarters?

Black Philosopher, White Academy tells Fontaine’s story. Raised in a poor and segregated community in Chester, Pennsylvania, in the early part of the twentieth century, he matriculated at the African American Lincoln University in 1926. Six years of advanced part-time graduate study at the University of Pennsylvania earned him a Ph.D. in philosophy in 1936. He then taught at Southern University in Louisiana and Morgan State College, two more all-black institutions. But the changing racial climate after his service in World War Two led to a permanent position in the philosophy department at Pennsylvania, where he made a career for two decades.

I have examined Fontaine’s ideas and the development of his thought, but more than anything else I have tried to get inside his head and understand his psyche. What did he make of his position? How did it feel to be in his shoes and walk his walk?

For many years one of the very few black academics in the white university world, Fontaine stood well nigh by himself at prestigious institutions as an African American. Perhaps of greatest significance, Fontaine remained alone as the only philosopher of color in the Ivy League at a time when philosophy had its place as a foundational discipline in the collegiate arts and sciences. He had entered the inner circle of what the Caucasian West conceived as its civilizing mission. An oddity in his time, Fontaine in many ways could not represent the overwhelming majority of African American scholars who never broke the racial line. He cherished his status and believed in the promise of American democracy that he personified. But his position took an enormous personal toll. The problematic evolution of his career illuminates both his exceptional nature and the common culture of one sort of “Negro intellectual.” African American determination and self-doubt formed this culture. So too did white racism, genuine moral principles on both sides, and the condescending liberalism particularly prevalent after World War II.

Fontaine climbed to the heights of this system. In putting his life in context, I have emphasized both the modern American university and the role of the professional philosopher within it. Of equal importance, I have looked at Fontaine’s understanding of African American history that for him and others shaped a commitment to a desegregated United States. These two frames of reference, the collegiate world and segregated America — one white, one black — molded Fontaine’s lived experience.

Fontaine was a teacher and mentor of mine, and in writing the book and attempting to give the man his due, I have often found myself paying a personal debt — but incompletely.