In the extended article that appears below historians Daudi Abe and Quintard Taylor explore the history of African Americans in King County from 1858 to 2014. They analyze the forces which encouraged people of African ancestry to settle in the county and discuss the rapid political, social, and economic changes that its Black residents have faced since the first arrival, Manuel Lopes, came to the county in 1858.

With 119,801 people of African ancestry in a total population of 1,931,249 people, King County is the most populous county in the state of Washington and is home to 29% of the state’s inhabitants and half of Washington’s Black population. It is also the only county in the United States named after the 20th Century civil rights icon, Martin Luther King, Jr.

King County, which is twice the size of Rhode Island, extends roughly 66 miles west from the Cascade Mountains to Puget Sound and 46 miles from its northern to southern limits. It was created on December 22, 1852, by the Oregon Territorial Assembly and thirty-six years later it was part of the state of Washington which entered the Union as the 42nd state on November 11, 1889.

The history of African Americans in King County began with the arrival of Manuel Lopes in Seattle in 1858. Lopes became the first barber in a town of 182 non-Indian inhabitants. He was followed by William Grose (Gross), in 1861. Grose also opened a restaurant and hotel, called “Our House,” located on the Seattle waterfront. Eventually, he added a barbershop as well. Grose’s hotel was destroyed in the Seattle Fire of 1889 but during the same period, he settled on a piece of land near what is now 23rd Avenue and Madison Street in Northeast Seattle, which became the center of settlement for the county’s earliest Black middle-class residents.

The handful of African American settlers like Lopes and Grose who first came to King County in the second half of the 19th Century were drawn by the region’s “free air,” meaning the absence of the most blatant policies and practices of racial discrimination that were a part of everyday life for Blacks in the South. African American men, for example, routinely participated in the civic life of the county at a time when voting prohibitions and terrorist tactics drove post-Reconstruction-era African Americans away from the polls in other regions of the country. Washington’s African American men voted throughout the Territorial period and the Washington Territorial Suffrage Act of 1883 briefly made it possible for black women to cast ballots until women’s suffrage was struck down by the Territorial Supreme Court in 1887.

By 1880 King County’s black population reached 34 individuals. Male pioneers were lured to the area by opportunities in construction, farming, and coal mining while women frequently worked as domestic servants or owned small boarding houses or stores.

In 1883, John and Mary Conna, formerly of Kansas City, Missouri, settled on 157 acres near what is now Federal Way, Washington in the southwestern part of the county. Conna, a Civil War veteran, became the first black political appointee in the Washington Territory when Republican Party leaders made him Assistant Sergeant at Arms of the 1889 Washington Territorial House of Representatives.

In 1886 black residents of Seattle established the earliest African American church in the territory, First African Methodist Episcopal or First AME Church. The second major black church, Mount Zion Baptist, was founded in 1894. Early area residents included Robert O. Lee who arrived in Seattle in 1889 and became the first practicing African American lawyer in King County. In 1895 John Edward Hawkins, who worked as a barber in Seattle while studying law at night, became the first locally trained black lawyer admitted to the King County Bar. In 1890 Isaac W. Austin, a former police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, became the first black officer appointed to the Seattle police force.

Political history was made in 1892 when Seaborn Collins faced John A. Coleman in a public election for the position of wreckmaster, the person responsible for the removal of accumulated timber on the waterfront. Coleman was the first black Democrat nominated for office in King County, and Collins held the similar position with the Republican Party. In the election Collins easily defeated Coleman to become Seattle’s first black elected official. The contest was also Seattle’s first city election that pitted two African American candidates from opposing political parties against each other for the same post.

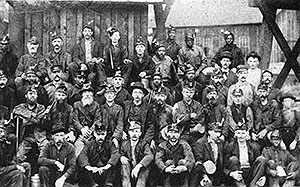

Although Seattle already had the largest black population in King County, a smaller concentration of African Americans formed in the coal mining towns of Newcastle, Franklin, and Black Diamond in the 1890s. African Americans were introduced into the Cascade Foothill Coal Mines as strikebreakers in 1891, a development that led to tension with the striking white miners and their families. By 1904 however these miners, recognizing their common interests, came together with white miners to form United Mine Workers (UMW), District 10, one of the first racially integrated local unions in the United States.

Some of the African Americans who first lived and worked in Newcastle, Black Diamond, and Franklin began to move into Renton, a small community about half way between the coal mining towns and Seattle. Sometime before 1910, James I. Smith settled in what is now the Hilltop area of Renton. He built a house and eventually added a smoke house, chicken house, and a garage. The ability of blacks to buy property in Renton and the apparently hospitable surrounding environment was enough for Smith’s brother, Dougherty, to purchase five acres in the same area a short time later.

Renton soon became a popular residential area for African American miners who worked in Newcastle. Considered the country by some, this area also represented an escape from what a few black Seattleites saw as the urban ills of the rapidly growing city on Elliott Bay. Other black miners and their families in other central Washington coal towns, such as Powell Barnett of Roslyn or their descendants, eventually migrated directly to Seattle as coal mining in the state declined in the 1920s.

Horace Cayton and his wife, Susie Revels Cayton, would become the most successful of the early 20th Century African Americans in King County. Horace Cayton, born the mixed-race son of a slave woman and white man in Mississippi, came to Seattle in 1889. Cayton married Susie Revels, the daughter of Mississippi Senator Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve in the United States Senate. Horace Cayton worked for a time as a political reporter at the city’s largest newspaper, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer before founding in 1894 the Seattle Republican, which became one of the most successful black-owned newspapers in the state’s history. Horace and Susie Cayton managed the Republican until its demise in 1913.

While the Caytons were by far the most prominent African American family in Seattle at the beginning of the 20th Century, by 1900 other pioneer black families had established themselves in King County including John T. Gayton of Mississippi who arrived in 1888, Lloyd and Emma Ray from Kansas, and Thomas and Margaret Collins from Georgia who all arrived in 1889. After retiring from the United States Army, Dr. Samuel Burdett, a veterinarian, and his family arrived in 1890. In 1891 John and Mary Cragwell came from Washington, D.C., followed later that year by former Arkansas state legislator Conrad Rideout and his family.

After losing his barbershop in the Seattle fire of 1889 William Scott and his wife Pauline moved southeast and became the first black residents of Kent. From their property the Scotts sold timber, leased roads that crossed their land to lumber companies, and operated a successful truck farm which sold to commission houses in Seattle.

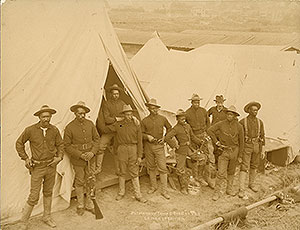

King County’s small African American community of 603 people in 1900 also included members of the U.S. Army’s 9th Cavalry, popularly known as the Buffalo Soldiers. These black soldiers were stationed at Fort Lawton in what is now Discovery Park in Seattle’s Magnolia neighborhood. From there they were sent to the Philippines to suppress the insurgents who first fought the Spanish and then challenged the Americans who now occupied the Islands. One soldier, Frank Jenkins, married a Filipina, Rufina Clemente, and settled in Seattle prompting the Filipino community to trace its history to their descendants.

Between 1900 and 1910 the number of blacks in King County grew from 603 to 2,487, a 312% increase. The vast majority of them settled in Seattle and a stable community was beginning to emerge. The growing numbers of black women were a major reason for that stability. Black women now played central roles in the two oldest churches, First AME and Mt. Zion Baptist. In 1906 Letitia Graves, wife of a Kansas stonemason who came with her husband to Seattle in 1884, created the Dorcus Charity Club along with Susie Revels Cayton, Alice S. Presto, and Hester Ray. The Club emerged as one of the top pre-World War II African American philanthropic organizations in Seattle. Graves was also the founder and first president of the Seattle branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was created in 1913.

Lodie Biggs, a bacteriologist, was one of the few professional black women in King County at that time. She was also a political activist who along with local attorney Clarence Anderson and newspaper editor William Wilson, reactivated the Seattle NAACP in 1928. Two years later Biggs founded the Seattle Urban League and served on its first Board of Directors.

Despite the integration of the United Mine Workers in 1904, most African American workers remained excluded from King County labor unions for the first three decades in the 20th Century. An important breakthrough came in 1934 when, following a bitter maritime strike that shut down the Seattle waterfront, members of the Colored Marine Employees Benevolent Association (CMEBA) and the all-white Marine Cooks and Stewards Association of the Pacific (MCSAP) merged into a single union. The same strike resulted in the integration of the International Longshoreman’s and Warehouseman’s Union (ILWU) as well. The 83-day strike created for the first time an interracial, all-union Seattle waterfront. Labor union discrimination against African Americans would continue through the late 1960s but the strike of 1934 clearly shifted the momentum toward interracial unionism.

By the 1930s King County blacks created a leisure culture centered on music and sports. Black musicians and performers, dating back to Bertram Philander Ross Hendrix and Zenora Moore, the grandparents of Jimi Hendrix, ushered in a musical scene that in the 1920s included local acts like the Edythe Turnham Orchestra, Oscar Holden, and the Black and Tan Jazz Orchestra. These musicians mostly played on Jackson Street and the south end of downtown at venues like the 908 Club and the Black and Tan nightclub. As one observer recalled, “you could see almost as many people at 12th and Jackson at midnight as you’d see on 3rd and Union (the center of downtown Seattle) in midday.” While the statement was an exaggeration, it also signaled the popularity of jazz music among whites as well as blacks. In fact Seattle’s mostly black jazz musicians often played in Asian American-owned clubs which in turn introduced them to a trans-Pacific jazz circuit that eventually included Shanghai, China and Manila, The Philippines.

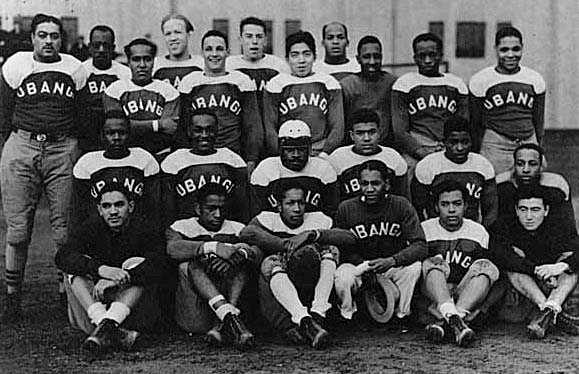

King County blacks also supported semi-professional football teams such as the Ubangi Blackhawks and baseball teams like the Seattle Royal (American) Giants. In 1937 the Blackhawks won the City Football Championship, and in 1938 the Giants won the comparable baseball title. In addition the Owls, Seattle’s black women’s softball team, won the state championship. These games became community events at Garfield Park, drawing crowds as large as 3,500 people. Much like their counterparts across the Northern states, these teams were often owned or financially backed by nightclub owners such as Russell “Noodles” Smith. Unlike the jazz musicians, they rarely played beyond the Pacific Northwest but they did entertain hundreds of black Seattleites on Sunday afternoons.

All of King County underwent a dramatic change during World War II. Seattle ranked third in the nation behind Detroit, Michigan and Los Angeles, California in the value of defense contracts from the Federal government between 1941 and 1945 and thus became a major defense production center. For African Americans this designation meant a time of unprecedented migration and opportunity. The population figures reflect that enormous change. In 1940 King County had 4,038 African Americans. Ten years later the black population reached 16,733, a 314% increase.

Most of these migrants came because of newly created work opportunities. Those opportunities evolved from two parallel developments: worker shortages and President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802, which banned racial discrimination in defense plants with government contracts. That meant the Boeing Airplane Company and other local firms such as Pacific Car and Foundry in Renton began to hire black workers for the first time.

As the largest employer in the Pacific Northwest, Boeing was the focal point for hiring. Under pressure from some within Local 751 of the Aero Mechanics Union, an affiliate of the International Association of Machinists (IAM), and black-led organizations outside the aircraft maker such as the Committee for the Defense of Negro Labor’s Right to Work at Boeing Airplane Company, Boeing agreed to take on black workers to help it meet its contract to supply thousands of bombers and other aircraft for the war effort. First hired was Florise Spearman, a stenographer who became an office worker in January 1942. Four months later Dorothy West Williams, a sheet metal worker, became both the first African American production worker at Boeing and the first black member of Local 751. By the end of the war in 1945, Boeing had hired 1,600 black workers, the vast majority of them women.

World War II also brought more complex racial dynamics to King County. African Americans still faced housing discrimination and in fact the influx of black newcomers intensified the concentration of African Americans in Seattle’s Central District, already by 1940 the home of the vast majority of blacks in the county. Racial friction intensified on city streets as Southern-born blacks often clashed with both white southerners who had also moved to Seattle in search of defense work, and local whites who were not accustomed to seeing large numbers of African Americans in the city. Tensions also emerged within the local black community between “old timers,” as the pre-World War II black residents were called, and the migrants. Eventually the local black churches set up the Committee for Tolerance which reduced some of the tension. The Christian Friends for Racial Equality, a Seattle-based multi-racial organization, also helped reduce interracial tensions and promoted civil rights for African Americans.

Partly because of these organizations the single worst incident of racial conflict during the World War II era happened not among civilians but at Fort Lawton in Northwest Seattle. On the night of August 14, 1944, several dozen black soldiers rioted at the military facility. During the confrontation an Italian prisoner of war, Guglielmo Olivotto, was lynched. Newspaper reports blamed the uprising on African American soldiers’ anger over the perception that Italian prisoners of war received better treatment than they did. In fact, the Italian POWs were allowed to visit local taverns that did not admit black military personnel.

The Fort Lawton Riot made national headlines, as did the subsequent court martial that brought up 44 African American soldiers on various charges from riot to murder. Eventually 28 soldiers were convicted, including two for manslaughter. Thirteen soldiers received acquittals, and two had all charges dropped. Following the end of the war several of the soldiers who received longer sentences were granted clemency, but still there were some who wound up serving as many as 25 years. Jack Hamann’s 2005 book On American Soil: How Justice Became a Casualty of World War II led to a reopening of the case by Army investigators. In 2008, with only two of the 28 soldiers still living, all the convictions were overturned, formal apologies and honorable discharges were offered, and families of the soldiers were awarded lost back pay.

Unlike many other areas around the United States that had boomed during the war only to see massive job losses and population declines, the emerging Cold War and the growth of air travel kept Boeing busy making both military and commercial planes into the late 1940s and early 1950s. In fact by 1951 national black news publications such the Chicago Defender called Seattle a “race relations frontier” and ranked it as one of the best cities in the nation for African Americans. It urged eastern blacks to move there.

The larger numbers of African Americans in King County in the 1940s now supported more venues for leisure. On June 1, 1946, the Seattle Steelheads, an all-black professional baseball team played its first game at Sick’s Stadium, located at the corner of McClellan Street and Rainier Avenue. The Steelheads were a part of the West Coast Negro Baseball League owned by Abe Saperstein, who also owned the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team. Made up of teams from Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, and Portland, the league had planned to play over 100 games but folded after only two months.

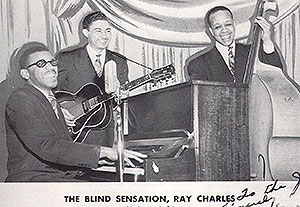

The expanded music scene proved far more enduring. Pre-World War II Seattle had already developed a reputation for its jazz played primarily along Jackson Street. World War II introduced Seattle jazz to a wider audience. It also drew 18-year-old Ray Charles from Tampa, Florida to Seattle in 1948. Charles, who began playing music at age three, lost his sight at age seven to glaucoma. He learned to read and compose music in Braille and mastered several instruments, including the piano, clarinet, and saxophone. In Seattle, Charles made a name for himself playing gigs for diverse audiences at the black Elks Club on Jackson Street, the all-white Seattle Tennis Club, and after-hours establishments such as the Black and Tan Club and the Rocking Chair, where he was eventually discovered and offered a recording contract. Ray Charles would ultimately record more than 60 albums, win 12 Grammy Awards, earn induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, and be awarded the Presidential Medal of the Arts in 1993.

Quincy Jones, who with his parents had moved from Chicago, Illinois first to Bremerton, Washington and then Seattle in 1943, gained his first musical experience doing gigs and writing arrangements while still at Garfield High School. As a teenager he played backup for some of the biggest names in music, including Louis Jordan, Billie Holliday, and Nat King Cole when they performed in Seattle during the post-war years. Jones’ big break came in 1950, shortly after he graduated from Garfield. With jazz great Lionel Hampton in town for a show, Jones was able to pass along one of his musical compositions to the famous bandleader. After his show, Hampton tracked him down and asked Jones to join his band. Jones accepted and over the next four decades he received 27 Grammy Awards, an Academy Award, and an Emmy Award. He also produced Michael Jackson’s album Thriller (1982), which is acknowledged as the highest selling album of all time.

It was also during the World War II years that one of black King County’s most incredible musical talents came into the world. Born in Seattle in 1942, Jimi Hendrix came of musical age in the city. In 1957, for example, at the age of 15 he was already playing guitar in a jazz combo led by Robert “Bumps” Blackwell which also featured a slightly older Quincy Jones. Hendrix left Seattle in 1961 after enlisting in the United States Army. Following an honorable discharge he lived briefly in Clarksville, Tennessee before moving to London, England, where his career took off. After scoring hits in the United Kingdom, Hendrix reached number one in the U.S. with his album Electric Ladyland (1968).

As the world’s highest paid performer at the time, Hendrix headlined the Woodstock Festival in upstate New York in August 1969 where he debuted his ground-breaking electric guitar rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Already known among rock musicians and their fans, Woodstock introduced Hendrix to a world-wide audience. Widely acknowledged as one of the greatest guitarists of all time, Jimi Hendrix died in London of a drug overdose on September 17, 1970 at age 27, just over a year after his performance at Woodstock. His body was flown back to Seattle, where the Hendrix family still resided, and buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Renton.

The large numbers of black women who arrived in King County during and after World War II found a number of new opportunities with Boeing and other wartime manufacturers although many of them continued to work as cooks, nursing aides, or laundresses. Following the war King County’s relatively tolerant climate allowed for a growing number of businesses owned by black women, which included restaurants, night clubs, and more often beauty salons.

Two areas, nursing and education, offered early professional alternatives for post-war black King County women. By 1949 13 black female nurses worked in Seattle with most of them at Harborview Hospital. Most were members of the Mary Mahoney Registered Nurses’ Club (MMRNC) in Seattle. Named after the first African American female registered nurse in United States history, the organization provided scholarships to young women pursuing careers in nursing.

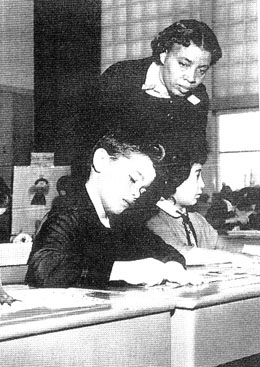

Seattle Public Schools were another place that offered professional options for black women. In 1947 Thelma Dewitty was the first black teacher hired to teach in Seattle’s public schools. One year later six black teachers, all women, worked at a number of elementary schools including Cooper, Horace Mann, Hawthorne, Summit, and Gatewood.

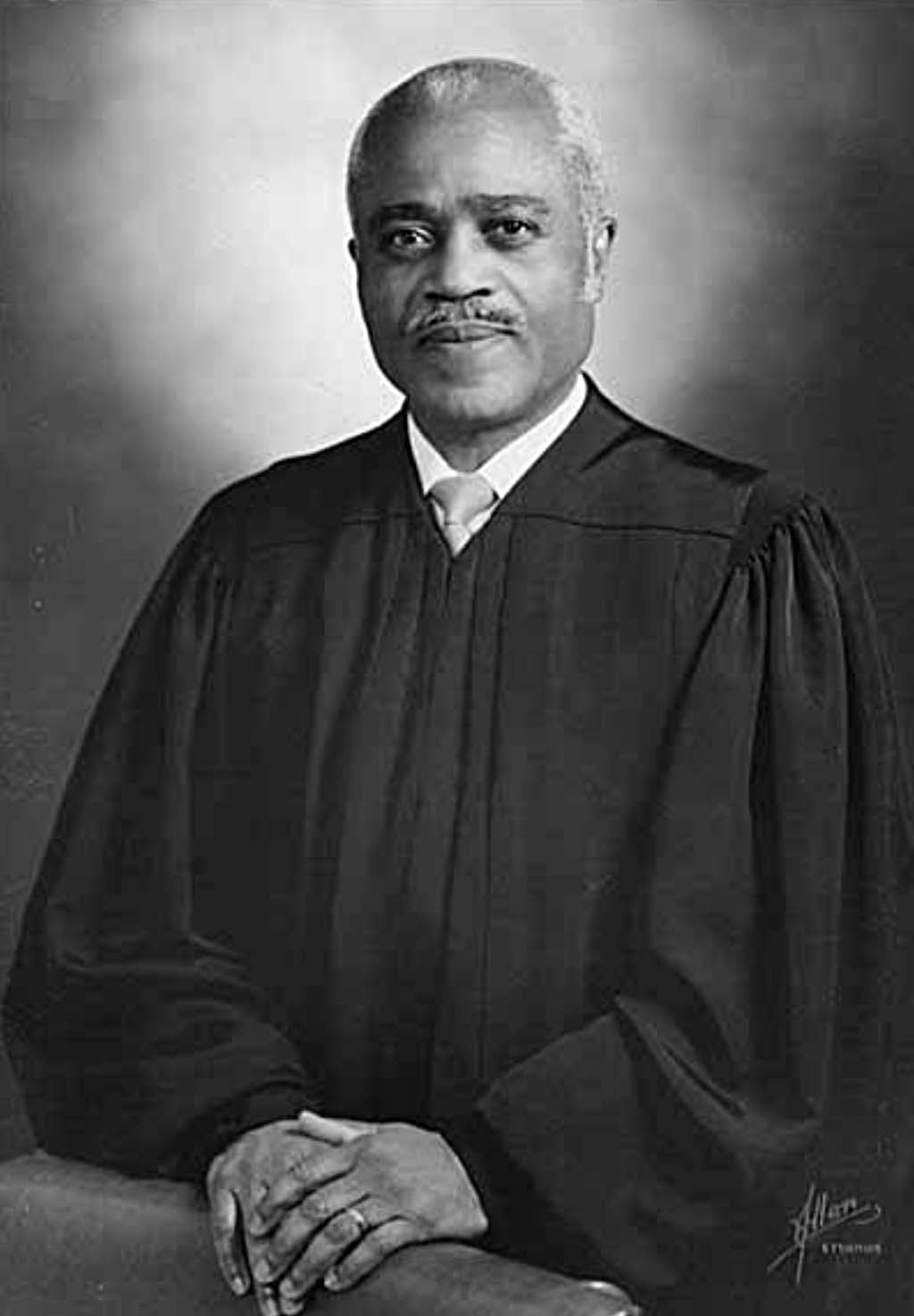

The post-1945 period in King County saw a number of other African American firsts. John Prim, a 1941 graduate of the University of Washington Law School, was appointed the first judge pro tem in King County in 1954, and Charles Stokes became the first African American elected to the Washington state legislature from King County.

Born in 1903 in Pratt, Kansas, Charles Stokes graduated from University of Kansas School of Law in 1931. When he moved his law practice to King County in 1943 there were fewer than five black lawyers in the entire state of Washington. In 1950 Stokes ran for the Washington State Legislature representing the 37th District in Seattle. When he won he became the first African American from King County elected to serve in Olympia, and only the third in Washington state history. He was re-elected twice, in 1952 and 1956. A lifelong Republican, Stokes spoke at the 1952 Republican National Convention in Chicago that nominated World War II hero General Dwight D. Eisenhower for President.

After he lost his seat to black Democrat Sam Smith in 1958, Stokes remained active in the community, helping to form Seattle’s first black owned radio station, KZAM, as well as the state’s first black owned bank, Liberty Bank. Stokes also continued a successful law practice and in 1968 he became the first African American judge appointed to the King County District Court.

During the post-World War II period and into the 1950s black civil rights organizations in King County became increasingly active in the struggle for racial equality. The Urban League of Seattle took a conservative approach which entailed negotiating with white business leaders to employ individual black workers. It was able to get jobs for African Americans in local retail stores, banks, and breweries for the first time. The Seattle branch of the NAACP was more confrontational; it initiated legal challenges to public accommodation discrimination and took on prisoner’s rights cases. In addition several members of the Washington State Board Against Discrimination (WSBAD) such as Ola Browning, Roberta Byrd, and Calvin Johnson, were active in both the Urban League and NAACP during the 1950s.

Unlike other west coast cities such as Portland, San Francisco, or Oakland which saw their post-war black populations stabilize or (in the case of Portland) decline, King County’s African American communities continued to grow rapidly, helped by the expanding economy in the region. With so many black newcomers arriving, fair housing and public accommodations became increasingly contentious issues in King County. In fact anti-discrimination legislation, enacted by the state legislature, was challenged in King County Court. In 1957 housing discrimination was declared illegal when the state legislature passed the Omnibus Civil Rights Act. This law, unusually progressive for its time, was undercut two years later by King County Superior Court Judge James Hodson in the case of O’Meara v. Washington State Board Against Discrimination. Hodson stated that while he recognized the “evils” of racial discrimination, the rights of owners of private property to deal with whomever they chose came first. Hodson’s ruling was subsequently upheld in both the Washington State Supreme Court as well as the United States Supreme Court.

Civil rights issues in the 1950s were a prelude to the explosion in activity among King County blacks and their supporters in the 1960s. However distant King County may have appeared from the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, it would quickly become part of that movement. As Rev. John Adams remarked, by 1963, “the Civil Rights Movement had finally leaped the Cascade Mountains.” Although blacks had been voters in Washington for almost a century and thus did not have to struggle for the ballot as did their counterparts in the Deep South, African Americans in King County faced three interrelated issues: job discrimination, housing discrimination, and de facto school segregation which collectively held back their educational and economic progress. Knowing this, King County blacks used the tools of direct action already employed in the South to challenge each issue.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the two major civil rights organizations in King County were the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (founded in 1913) and the National Urban League (founded in 1930). These local branches of their respective national organizations had engaged in limited and sporadic challenges to the various types of discrimination faced by King County blacks in the first five decades of the 20th Century.

As the Civil Rights movement began to gain momentum both nationally and locally, more groups began to appear that could capitalize on this momentum. One of these was the Seattle chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) which was originally founded in 1942 in Chicago, Illinois. Ken Rose, Ray Cooper, Norman Johnson, and Ed and Joan Singler were instrumental in establishing CORE’s presence in Seattle in 1961. Ray Williams was the group’s first chair, with Ed Singler serving as vice-chair.

Multiracial in membership and nonviolent in its approach, CORE’s Seattle chapter developed a reputation as one of the most effective in the country. Beginning in October of 1961, CORE targeted supermarkets around the city and retail establishments in downtown Seattle that were known for engaging in racist employment policies. The group selected supermarkets like Safeway and A & P for what were known as selective buying campaigns, which encouraged black patrons and their allies to boycott stores that refused to hire African Americans. One particularly contentious tactic was the “shop-in,” where activists filled shopping carts full of goods, went through checkout lines, and then abandoned the carts without paying.

After CORE’s successful efforts against grocery stores, downtown businesses such as Nordstrom and J.C. Penney now faced protests and picket lines over discriminatory hiring practices, including a march on the Bon Marché (now Macy’s) that attracted over 1,000 people in 1963. Eventually known as the Drive for Equal Employment in Downtown Seattle (DEEDS), CORE led a four month boycott of downtown stores when business leaders ignored a DEEDS report that highlighted discriminatory hiring practices and outlined solutions. These direct action protests were credited with helping to create hundreds of job opportunities for African Americans in Seattle’s downtown retail core throughout the 1960s. As a consequence of this campaign, Nordstrom, became the first major retailer in the nation to create a voluntary affirmative action program.

The Civil Rights movement in King County was powerful enough to attract a visit from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who arrived on November 8, 1961. King was invited to participate in a lecture series sponsored by Mount Zion Baptist Church and its pastor, the Reverend Samuel B. McKinney who was a classmate and friend of King from their days together at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. On his only visit to the Seattle area, King gave four speeches in two days. On Thursday, November 9th he spoke at the University of Washington and Temple De Hirsch Sinai, and on Friday, November 10th at Garfield High School and the Eagles Auditorium, now the ACT Theater.

Throughout the 1960s the focus of many King County civil rights organizations was fighting housing discrimination. Like their counterparts across the nation, housing activists took on a process that involved individual discrimination, restrictive covenants maintained by neighborhood associations, and “redlining.” With redlining, the Federal government itself through policies of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), actively encouraged disinvestment in black or mixed-race neighborhoods by discouraging loans in those areas by banks, savings and loan associations, and other financial institutions.

While local organizations may not have recognized the relationship between all three forms of discrimination, they understood that African Americans throughout King County could not live in neighborhoods of their choice regardless of their financial resources. They vowed to bring that exclusion to a halt. Their goal was the enactment of anti-discrimination laws or ordinances across the county that would create what they called open housing, or the right of individuals to live where they wished regardless of their race.

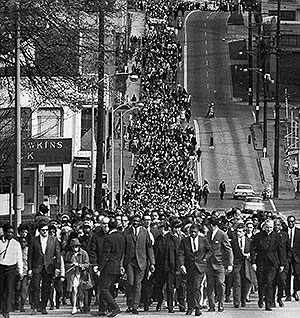

After a citizen’s advisory committee, appointed by Seattle Mayor Gordon Clinton, recommended a citywide open housing ordinance for Seattle in 1962, the Mayor and the City Council refused to act on the measure for over a year. In response Reverend Samuel McKinney and Reverend Mance Jackson led 400 marchers from Mount Zion Baptist Church to City Hall on July 1, 1963.

Embracing the civil disobedience tactics that were already occurring across the nation, 35 members of an interracial organization called the Central District Youth Club broke off from the march and staged Seattle’s first sit-in when they occupied the mayor’s office for 24 hours. This was followed up on July 20th by a 300 person sit-in at the chambers of the City Council, which resulted in the arrest of 23 protesters. Coinciding with the 250,000 person March on Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963, over 1,000 people marched from the First AME Church to the Federal Courthouse in downtown Seattle to protest a number of grievances including housing discrimination.

The pressure brought by these demonstrations continued to mount until the City Council enacted Seattle’s first open housing ordinance at its meeting on October 25, 1963, which made housing discrimination a misdemeanor and a finable offense. Open housing opponents, however, drafted a petition and were able to gather enough signatures to get the measure on the ballot for a citywide referendum in March of 1964, where it was rejected by a more than two to one margin.

Open housing advocates refused to give up. They continued to stage protests and over time gathered increasing support for their cause. Meanwhile the efforts of individuals such as Sidney Gerber, a builder who insisted that the housing he constructed in the city and its suburbs be open to all, and efforts like the Seattle Urban League’s Operation Equity, opened housing to African Americans throughout the county.

Over time their efforts persuaded others to support residential integration. By early 1968, 30,000 King County residents mostly outside the city of Seattle signed open housing petitions indicating that they would welcome black neighbors. Those petitions, as much as any action taken by local governments, signaled an increasing acceptance of African American neighbors in many areas of the county. On April 19, 1968, 15 days after the Dr. Martin Luther King assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, the Seattle City Council passed an open housing ordinance sponsored by City Councilman Sam Smith but now endorsed by a broad range of organizations across the city.

The growing call for open housing touched areas of King County outside Seattle. In 1962 a Boeing chemist named Harold Booker attempted to purchase a home for his growing family in Federal Way. Most Federal Way real estate agents refused to do business with African Americans, and Booker was able to build his own home only when a white colleague at Boeing deeded him a piece of land. Following a racist experience when his family visited a local swimming pool, Booker started the Federal Way Human Rights Committee (FWHRC), a mostly white group, in 1963 that focused on eliminating racist housing policies. The FWHRC called for action on the issue from the King County Council and actively recruited African Americans to come and live in Federal Way.

De facto school desegregation (racial isolation despite the absence of formal segregation laws or public officials who openly supported racial separation), proved the most difficult issue facing King County blacks and the only one that lasted long after the end of the 1960s. The roots of the conflict could be traced to World War II. Although Washington had been one of the few states in the nation to enter the Union in 1889 with a constitution that barred racial segregation in public schools, the overwhelming concentration of African Americans in Seattle’s Central District beginning in World War II and continuing through the 1950s ensured that schools would be racially segregated. In 1950 none of Seattle’s elementary and secondary schools were predominantly black. The first enrollment census of Seattle public schools in 1957, however, showed that while only 5% of the city’s 91,782 students were black, nine elementary schools, eight of which were in the Central District, contained 81% of all elementary age black students in the city. By 1962 Garfield had become the first predominantly black high school in the state’s history.

Seattle’s educational establishment at the time refused to take responsibility for the growing isolation of black children in the city’s public schools. School leaders argued with some justification that housing patterns over which they had no control created this de facto segregation. Henry B. Owen, Seattle School Board President in 1954, the year of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, spoke for the board and much of Seattle when he said, “Our feeling at the time was that it was not our fault that the schools were segregated.”

For King County civil rights leaders such an answer was unacceptable. Quality education, which they equated with racially integrated education, became their exclusive goal. They and civil rights leaders across the nation, as well as most African Americans at the time, believed that while it was important to challenge all forms of discrimination, improving education for black children was the key to economic and social advancement for individual and group progress. Thus it is no surprise that they invested heavily in the campaign to end de facto school segregation. CORE chairman Walter Hundley expressed the fear of many black King County leaders when he said, “We know the consequences when Negroes are forced to go to school together in their penned up sections of the city. They learn to hate.”

In the early 1960s at least, Seattle civil rights leaders seemed to have allies on the Seattle School Board. On August 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington, D.C, where 250,000 people gathered at the nation’s capital to demand Congress pass the stalled Civil Rights bill, and where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would deliver his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, the Seattle Public School District became the first major school system in the nation to voluntarily adopt a citywide school desegregation program.

In the early 1960s at least, Seattle civil rights leaders seemed to have allies on the Seattle School Board. On August 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington, D.C, where 250,000 people gathered at the nation’s capital to demand Congress pass the stalled Civil Rights bill, and where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would deliver his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, the Seattle Public School District became the first major school system in the nation to voluntarily adopt a citywide school desegregation program.

Over time, questions around integrating schools in Seattle and other King County cities became layered and complex as the issue evolved. The initial narrative that school integration was the best way to ensure equal educational opportunities for all children would eventually be challenged within the local African American community. In 1963, however, the civil rights establishment and most people who considered themselves racial progressives, regardless of their race, embraced the idea that Seattle schools must be racially integrated as that process would be the only way to assure quality education for black students.

That civil rights establishment was in place by 1963 and represented one of the few examples in the nation of a unified movement committed to a single set of tactics and goals. In 1963 a group of high profile leaders from the major civil rights organizations formed the Central Area Civil Rights Committee (CACRC). Its membership included Edwin Pratt of the Urban League, Walter Hundley of CORE, Seattle NAACP branch president E. June Smith, and former branch president Charles Johnson as well as ministers such as Reverends Mance Jackson of Cherry Hill Baptist Church, Samuel McKinney of Mount Zion Baptist Church, and John H. Adams of First AME Church. These leaders, all middle-class reformers committed to racial integration not only in the Seattle schools but in every aspect of community life, spoke with a single voice on local civil rights issues.

With the exception of E. June Smith, the civil rights leadership in King County was all male. That apparent fact, however, obscures the crucial role of hundreds of black women in other roles including as front-line demonstrators. Bettylou Valentine, for example, was a member of CORE and responsible for the organization’s public relations and advertising. Seattle native Freddie Mae Gautier marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the South but also played a supporting role in the local challenge to discrimination. Later she became a political activist who organized black voters while helping a growing number of African American politicians win elective office. Her work helped ensure that the civil rights gains of the 1960s would be permanently ensconced in legislation.

In 1964 CACRC seized an opportunity to push the issue of de facto segregation by focusing on Horace Mann School in the Central District. The school, which was 97% black at the time, was housed in a crumbling building scheduled for demolition. For CACRC, this seemed the perfect opportunity to push for closure of Horace Mann so that its black students could be distributed to other schools around the city, thus encouraging racial integration. The NAACP went even further, calling not only for the closure of Horace Mann, but Washington Middle School, and Garfield High School as well since all were predominantly African American.

By 1965 neighborhood activists like Isaiah Edwards and Gertrude Dupree, as well as many working class African Americans, began to push back as they realized actual implementation of this type of school integration would put a disproportionate burden on African American children who would be bussed far from home. Those in favor of integrated education held the view that every segregated school represented a substandard educational experience. Edwards, Dupree and others who supported them, saw value in places like Horace Mann and Garfield High School. The opposing views of African Americans in this debate encapsulated the “integrationist” vs. “black power” approach that would eventually play out both in King County and on a national stage.

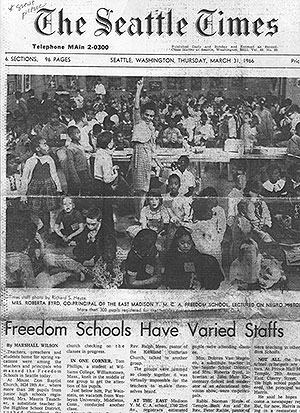

In the spring of 1966 the integrationists garnered their last major victory in the evolving conflict. In the face of CACRC demands for the closing of black neighborhood schools and the mandatory busing of African American students to predominantly white schools in distant neighborhoods, the Seattle School Board hesitated. CACRC responded by calling for a school boycott to demonstrate African American unhappiness with what it saw as delay tactics on the part of the school board. CACRC member E. June Smith was the driving force behind the student boycott.

The boycott took place on Thursday, March 31 and Friday, April 1, 1966 and included some 3,000 black students mostly from Central District schools as well as 1,000 white and Asian children from schools all over the city. Instead of attending their regular schools on those days, participating students reported to “Freedom” schools, which had been set up at various churches and community centers in the Central District to support the boycott. Over 500 children showed up at Mount Zion Baptist Church. At the Freedom schools most students sat in an integrated classroom for the first time while they studied African American history, arts, music and crafts, Native American culture, and the reasons for and meaning of the boycott. The scale of participation surprised even the boycott’s organizers, and revealed impressive levels of white and Asian support for school desegregation.

Despite this support, there was growing distance between those who believed in integration and those who supported what was now called “black power.” While there had always been some opposition to CACRC leadership over school integration and other civil rights issues coming from a variety of voices ranging from Edwards and Dupree to the Nation of Islam which first appeared in Seattle in 1961, that opposition now galvanized behind the slogan and quickly evolving ideology of black power which was first articulated publicly by Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chair Stokely Carmichael.

During the March Against Fear which was hastily organized in Mississippi following the attempted assassination of James Meredith, who in 1962 had become the first African American student to attend the University of Mississippi, Carmichael openly feuded with Dr. Martin Luther King as they led civil rights protestors down the route Meredith had vowed to follow. On June 16, 1966 in Greenwood, Mississippi Carmichael gave a speech which stated his organization’s intent to move from racial integration as a goal toward instead organizing the latent economic and political power of working class African Americans. He ended his speech with the question, “What do we want?” which was followed by the crowd’s response, “Black Power!” That speech forever changed the discussion about the goals of the civil rights movement and brought into question whether such a movement should continue to exist. Its impact reverberated across the United States and soon enveloped the King County black community.

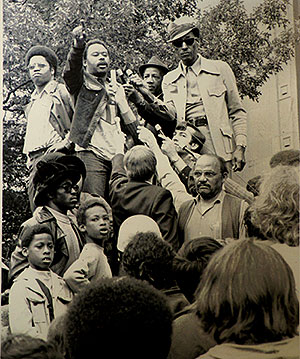

In this highly charged atmosphere Stokely Carmichael came to speak in Seattle on April 19, 1967. He gave speeches at the University of Washington and Garfield High School where an estimated 4,000 people heard his address. Those speeches resonated with younger African Americans including University of Washington student-activists Larry Gossett and Aaron Dixon (as well many white and Asian high school and college students). Carmichael was bold and unapologetic as he attacked integrationists, institutionalized racism, and the white press while encouraging Seattle blacks to “take control” of their community and their destiny.

Supporters of racial integration seemed dismayed and isolated as Carmichael’s sentiments were quickly embraced by the vast majority of young people, the very group that had supplied the support troops for civil rights protests in King County over the past seven years. In King County as elsewhere the term “negro” was suddenly replaced by “black,” not only in speech but in thought as well. Meanwhile CACRC no longer served as the undisputed leadership voice for black King County after Carmichael’s visit. The issue that had promoted the local split between integrationists and black power advocates, how to ensure quality education for African American students, would continue to be one of the most contentious in King County, and the nation, for decades to come.

As the civil rights movement unfolded across King County, African American political influence expanded dramatically. Much of this expansion reflects both local and national trends evolving from direct action challenges to racial discrimination. Black voters became more politically active because of these challenges and in King County at least, white and Asian voters were increasingly willing to cast ballots for black candidates for political office. That change was first evident in the city-wide election of Sam Smith in 1967 to the Seattle City Council where he became the first African American to serve on that body.

Sam Smith was a state legislator who lost to and then defeated the incumbent Republican Charles Stokes, in successive elections in 1956 and 1958. Born in Louisiana, Smith first came to Seattle in 1942 while serving in World War II. After the war he returned to the city, got married, and earned a degree in Economics from the University of Washington. Smith served nine years in Olympia representing the 37th District as the Civil Rights Movement unfolded, and then left the legislature in 1967 to run for the Seattle City Council. Although Smith ran twice for mayor, losing both times in 1969 and 1981, he also served as President of the City Council for eight years. Sam Smith helped lay a foundation for numerous future politicians of color in King County who would follow in his footsteps.

The year 1970 proved a milestone in terms of the number of African Americans winning public office in King County. In addition to Sam Smith, who was already a member of the Seattle City Council, former UW football star George Fleming, a Democrat, became the first black politician elected to the State Senate to represent the 37th District. Also representing the District in the State House of Representatives were Democrat Peggy Maxie and Republican Michael Ross. This was the only time in the history of the 37th District that African Americans occupied all three legislative positions.

Peggy Maxie was the first of a wave of black female officeholders who addressed particular concerns among women. She promoted a legislative agenda which supported childcare, education, tenants’ rights, and greater assistance to welfare mothers. In 1973 she successfully sponsored Washington’s no-fault divorce law, a reform that changed the impact of divorce on all women (and men) in the state of Washington.

Peggy Maxie was the first of a wave of black female officeholders who addressed particular concerns among women. She promoted a legislative agenda which supported childcare, education, tenants’ rights, and greater assistance to welfare mothers. In 1973 she successfully sponsored Washington’s no-fault divorce law, a reform that changed the impact of divorce on all women (and men) in the state of Washington.

The clash between the dominant culture of the era and the new black racial consciousness symbolized by the term black power played out across the nation, and King County was no exception. Numerous episodes reflected that clash but two incidents in 1968 at Franklin High School and the University of Washington stand out both for the attention they received then and for their long term consequences.

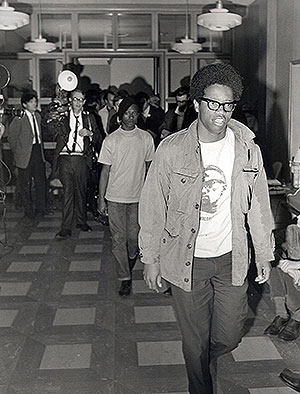

The Franklin incident began on March 29, 1968 when word spread that two black female students had been sent home for wearing their hair in an “Afro” style. University of Washington Black Student Union (BSU) members Larry Gossett and Aaron Dixon along with Seattle SNCC chairman Carl Miller arrived at Franklin and led nearly 200 students into the principal’s office with a list of demands. The demands included the addition of black history to the curriculum, the hiring of a black teacher and administrator, and the students’ right to wear hair as they pleased.

While district superintendent Forbes Bottomly quickly agreed to the demands, Gossett, Dixon, and Miller were later arrested and convicted on charges of unlawful assembly. Their sentence of six months in jail spawned an uprising at Garfield High School, where several hundred students had gathered in protest. Six people were arrested following several hours of unrest.

After the charge of unlawful assembly was overturned on appeal, the Washington State Supreme Court reinstated it. However, King County Prosecuting Attorney Charles Carroll decided not to retry the case. The Franklin episode was seen as a victory for the protesting students and their leaders and would usher in numerous other challenges as many black youth rebelled against both the black civil rights establishment and the white “power structure.” The protest at Franklin would be long remembered as the beginning of a new wave of black power activism in King County.

Unknown to school administrators or police, the Black Student Union (BSU) had been founded at the University of Washington in March 1968, only weeks before Gossett, Dixon, and Miller came to the Franklin campus. The three were part of a larger group of black (and a handful of Latino and Native American students) who organized themselves as the BSU to demand changes at the University. Shortly after the BSU formed, they delivered a list of demands to University President Charles Odegaard. The students wanted more aggressive minority recruitment of students, faculty, administrators, and counselors as well as a cultural center on campus. They also called for “adequate” financial support for minority students, a revision of admissions requirements to allow more non-traditional students, e.g., minorities and impoverished whites, and a Black Studies Program. University administration initially rejected these demands. In response 40 BSU members, some of whom ascended by rope up the side of the UW Administration Building, initiated a sit-in at the President’s Office on May 20, 1968. After four hours, the President and Faculty Senate leaders agreed to most of the students’ demands.

Certainly the national situation was one reason for the quick response by University officials, many of whom were sympathetic to their goals. In the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. less than two months before on April 4, 1968, University President Odegaard himself spoke of the need to purge racism from the campus and the society and urged white students to make an extra effort to compensate for past years of unequal treatment.

The assassination of Dr. King in Memphis, Tennessee sent shockwaves across Seattle and the entire nation. While King County was spared the days of rioting that occurred in more than one hundred cities across the country in the wake of King’s death, many county residents were moved by his untimely passing. Only days after the assassination, a crowd of over 8,000 people walked from the Central District to the Seattle Center for a memorial service. Washington Governor Dan Evans participated in that march. Originally slated to take place in the Seattle Center Arena, the venue was changed to Memorial Stadium to accommodate the crowd. Seattle Mayor Dorm Braman set aside April 8th as a day of mourning and remembrance in the city.

While most in King County mourned King’s death, others saw the assassination as the catalyst for a new stage of protest and direct confrontation. No group symbolized this change more than the Seattle Chapter of the Black Panther Party. By the time of King’s assassination, a number of “black power” groups already existed in Seattle including SNCC, the Central Area Committee for Peace and Improvement (CAPI), and the United Black Front (UBF). None of these groups however resonated with a small core of UW student activists. Aaron Dixon, Larry Gossett, and Carl Miller, who led the Franklin High protests, traveled to San Francisco, California soon afterward to attend the Western Black Youth Conference in March 1968. While there Dixon attended the funeral of 17 year-old Bobby Hutton, the first Black Panther killed by the Oakland Police.

The Panthers were formed in Oakland in October 1966 and by 1967 had emerged as the most recognized black militants in the country after they walked into the California State Capitol Building in Sacramento with loaded shotguns and rifles. The Panthers represented the new black militant attitude; they were stern and unflinching in demeanor and in their critique of the Oakland police and the Federal government, they wore black leather jackets and berets, and promoted socialism.

Aaron Dixon met briefly with Panther co-founder Bobby Seale during his trip and invited the Panther leader to Seattle. Events moved quickly. Seale visited Seattle on April 13, nine days after the King assassination, and while there appointed nineteen-year-old Dixon as Captain of the Seattle chapter of Black Panther Party.

Dixon quickly made the Panthers locally prominent. Monitoring the Seattle Police in the Central District was one of their first acts, a move that won them supporters among those who had long felt victimized by law enforcement but in doing so they also became the target for intense police surveillance and harassment. On July 29, 1968, Seattle police raided the Panther headquarters, arresting Dixon and Panther co-captain Curtis Harris on suspicion of possession of stolen property: a typewriter. The raid triggered the first race riots in the Central District. Seven police officers and two civilians were injured and 69 people were arrested despite a plea for calm by Dixon and Harris from jail. The two were later acquitted on charges related to the typewriter.

After reports of several interracial fights at Rainier Beach High School, a group of 15 armed Panthers, led by Dixon, went to the school and confronted Principal Donald Means on September 6, 1968. At the time Rainier Beach High School had around 2,000 total students, 100 of whom were black. After receiving assurances of the safety of black students, the group left before the police arrived. In February 1969 armed Panthers, mirroring what had happened in Sacramento in 1967, joined with members of CORE and the UBF to deliver a list of Central District demands to the Senate Ways and Means Committee at the State Capitol in Olympia.

Although actions like these marked the Panthers as thugs and terrorists by many people in Seattle, including a number of African Americans, they also launched a free health care service which eventually evolved into today’s Odessa Brown Clinic, set up prison visitation programs, initiated a sickle-cell anemia testing program, and ran a free breakfast program for children in need. They also placed candidates for the 37th District State Legislative seat on the ballot for election in the fall of 1968.

While the story of the Black Panther Party continues to be dominated by male actors both locally and nationally, Seattle women Panthers, like their counterparts across the nation, participated in a variety of party activities. Joan (Dixon) Harris, the sister of Seattle Black Panther Party Captain Aaron Dixon, for example, was a founding member of the local chapter. Maude Helen Allen was captain of women, Kathleen M. Halley was deputy minister of finance and treasurer, and Alice Spencer was communications secretary. Years later Panther Michael Dixon, younger brother of Aaron Dixon, pointed out that female members often challenged male chauvinism within the party.

Assassinations marked the 1960s throughout the United States. The murders of President John Kennedy and Mississippi NAACP official Medgar Evers (1963), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy (1968) as well as a host of other leaders and activists who met their death at the hands of assassins, marked the decade as particularly violent. Seattle, it seemed, had escaped that type of violence. That changed on the night of January 26, 1969 when Edwin Pratt, a Bahamas native, Atlanta University graduate, and Executive Director of the Seattle Urban League, was shot on the front porch of his Shoreline home.

Considered the “Dean” of local civil rights leaders, Pratt had led the Urban League since 1961. Despite finding a shell casing at the scene, witnesses who claimed to have seen two men running from the Pratt home to a waiting car after the shooting, and FBI involvement in the investigation, the killers were never found. Pratt, who was 38 years old when he died, left behind a wife and two young children. His funeral at St. Mark’s Cathedral was attended by more than 2,000 people including Seattle Mayor Floyd Miller and Washington Governor Daniel Evans. Today there are two lasting tributes to the Urban League leader: Edwin Pratt Park, located at the corner of 20th Avenue South and East Yesler Way in Seattle, and the Edwin Pratt Art Institute across the street from the park.

As the 1970s began, the struggle for black access to jobs shifted to the lucrative construction industry and the building trades unions that determined employment at the worksites. Those unions were the last major labor organizations in King County to openly practice racial discrimination. The five largest unions in November 1969 had nearly 15,000 members but only 29 were African American and 23 of them were in the Operating Engineers union. Of the 2,600 members of the plumbers union, only one was African American. The 850-member Iron Workers union also had only one African American member. When union members worked on major construction projects in the Central District at a time when unemployed blacks could only watch through construction fences, many in the community felt this last blatant example of Jim Crow unionism in King County had to be challenged.

In August of 1969 Tyree Scott, a black Seattle contractor, joined the Central Contractors Association (CCA) to draw attention to the exclusionary practices of these labor unions. Beginning on August 28, 1969 Scott led demonstrations that shut down construction sites at the Garfield High School swimming pool, the King County Courthouse, and Harborview Hospital to protest the fact that all the workers at these job sites were white. In September CCA members clashed with police during a protest at a construction site at the University of Washington.

While the protests provided a visible public response to the continuing discrimination, the lawsuit filed by the CCA which named five Seattle unions as defendants ultimately proved more successful. Scott and his supporters got a surprise boost when the Nixon Administration’s Department of Justice joined the case and sided with the CCA. Ultimately in 1970 Federal Judge William Lindberg cleared only one union, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 46, of wrongdoing. Four others, Iron Workers Local 86, Sheet Metal Workers Local 99, Plumbers and Pipefitters Local 32, and Operating Engineers Local 502 were all found to be in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The judge cited various underhanded tactics by the unions, including artificially inflated standards for blacks on aptitude tests, as evidence that major structural changes were needed.

Judge Lindberg devised what would be called “The Seattle Plan” which forced these unions to open their membership to black workers and provide them their own apprenticeship program. The plan adjusted admission requirements to reach journeyman level, and ordered that 45 black journeymen be admitted immediately. The Seattle Plan became a national model for affirmative action in the construction industry.

The 1970s represented another major turning point in the history of black King County. During the decade the African American population grew from 40,397 to 55,950, a 38% increase, proving that Seattle was still an attractive place for newcomers. The 1970s were also the first decade where the gains of the civil rights movement both locally and nationally were being consolidated. Although busing remained contentious throughout that decade and beyond, many black children now received an education outside the Central District. A small but growing number of blacks entered colleges and universities across the state as affirmative action programs and other compensatory measures encouraged their enrollment. Not surprisingly a significant black middle class began to emerge in the 1970s brought about by educational gains and an influx of African American professionals from across the nation to staff positions in educational institutions, government agencies, and private corporations such as Boeing.

The Boeing recession of the early 1970s hurt the entire regional economy, especially when the airplane giant cut its workforce from over 100,000 to less than 38,000 employees between 1969 and 1973. Those reductions forced business and political leaders to recognize the need to diversify the local economy and they began to promote other industries. It is no surprise then that by the mid-to late 1970s, new corporations representing new brands and new opportunities began to emerge in King County. Starbucks was the first but it was followed by Costco later in the decade, Microsoft in the 1980s, and Amazon in the 1990s. This new corporate presence in King County helped lure black professionals including women, who would change the face of power and influence in the region.

The rise of these new corporations had a variety of intended and unintended consequences for African Americans in King County. The corporations, especially by the 1980s, brought out or promoted a small cadre of African Americans and particularly black women such as Trish Millines Dziko at Microsoft and later founder of Technology Access Foundation (TAF) and the TAF Academy, Wanda Herndon at Starbucks, and Mary Pugh at Washington Mutual into significant leadership roles.

Like its counterparts across the nation, black communities in King County became more economically stratified. While some African Americans in the County brought in six-figure incomes, others became more deeply mired in poverty. Most of the reasons are well known: the loss of unskilled or industrial jobs, continuing educational disparities, the dramatic rise in drug use including especially “crack” cocaine and relatedly in crime and incarceration all caused the breakdown of many black working class families. The growing success and prosperity of well-educated blacks stood in sharp relief to the concentrated poverty of one third of the African American population. All of these changes meant that for King County African Americans, the 1980s and 1990s were both the best and the worst of times, sometimes even within the same family.

Major black churches, fraternities and sororities, and civic groups such as the Seattle Links and the Breakfast Group, all devised ways to battle this growing economic and social gap between King County African Americans. All of these groups employed long used strategies such as individual or group mentoring of young people or scholarships to increase college access. They also started computer clubs or sponsored job fairs to build opportunities for young people. Sometimes their programs and projects competed against and at other times blended with various government programs to help the poor and spur economic opportunity.

Not all organizations focused on the poor. Prior to 1970 new arrivals, especially black women, were able to rely on extended family and traditional community networks in the Central District to help ease their adjustment to King County. By the 1980s however, open housing legislation shifted the local black demographics as many of these new, single, professional, African American women transplants moved into Seattle city and suburban neighborhoods where there were few African Americans. Recognizing this change, Constance Rice, wife of future Seattle mayor Norm Rice, founded an organization in 1984 known as 101 Black Women. The goal of 101 Black Women was primarily to provide networking opportunities for women of color who felt increasingly isolated working and living in King County communities that were overwhelmingly white.

Rice was in fact a role model for many of these women. As early as 1985 she was named one of Seattle Weekly’s 25 most powerful women in Seattle. In 1992 she became the vice chancellor for Seattle Central Community College, and in 2013 she was appointed to the University of Washington Board of Regents by Governor Jay Inslee.

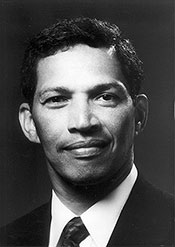

Rice’s appointment was the latest in what was now four decades of black involvement in the field of local educational leadership and policy making dating back to 1969. That year Alfred Cowles became the first African American elected to the Seattle School Board. He served until 1973 and was replaced by Carver Gayton who was appointed to complete Cowles’s term early that year and then elected to a full term in 1973. Dorothy Hollingsworth became the first black woman in the state of Washington to serve on a school board when she was elected to the Seattle School Board in 1975. She became the first black board president four years later. In 1981 Thomas J. (T.J.) Vassar, at age 30, became the youngest person ever elected to the Seattle School Board where he served two terms. Vassar was joined that year by Michael Preston, who would become a prominent voice on the Board for the next two decades.

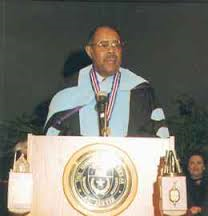

Donald Phelps was never elected to public office. Beginning in 1963, however, he became one of the most high profile black educators in King County, when he, at the age of 34, was hired as principal at Bellevue’s Robinswood Elementary. With that hire he became the first African American principal in a suburban Seattle community and later in 1967 he became the first black secondary school principal in the state of Washington when he took over at Bellevue Junior High School. After leaving in 1968 to become a commentator for KOMO television, Phelps returned to education as interim Superintendent of Lake Washington School District in 1976. Phelps moved into higher education in 1980 when he was hired as president of Seattle Central Community College, and then as chancellor of the Seattle Community College District in 1984.

Charles Mitchell, a Seattle native who starred on the University of Washington football team in the early 1960s, was named the second black president of Seattle Central Community College in 1987. He served until 2003. Under his tenure Seattle Central was named “College of the Year” by Time magazine in 2001-2002. In 2003 Mitchell became Chancellor of the Seattle Community College District and remained in that post until his retirement in 2008.

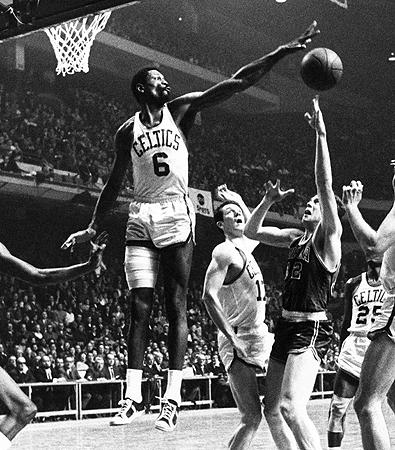

Professional sports also changed the face of Seattle and King County. Between 1967 and 1977 Seattle acquired new professional basketball (Supersonics, 1967), football (Seahawks, 1976), and baseball (Mariners, 1977) franchises. Given the visibility, influence, and in the case of basketball, dominance of black players, highly paid African American athletes would for the first time place their mark on the entire popular culture of the region. The first of these athletes was basketball great Bill Russell who arrived in the area in 1973.

Russell, a Louisiana native, had established himself as a basketball legend first at the University of San Francisco where his team won consecutive NCAA Championships (1955 & 1956), then at the 1956 Olympics where he was captain of the gold medal winning United States Men’s National Team, and finally in Boston, Massachusetts where he led the city’s Celtics to 11 NBA Championships, including eight in a row, in his 13 year professional career.

In 1966 Russell became the first African American coach in NBA history when he took over as player-coach for the Celtics. The following season he also became the first black coach to win an NBA Championship. Russell was also a leader off the court and active in civil rights, as evidenced by his role in convening a summit of top black athletes to meet with and support Muhammad Ali when the boxer challenged his draft by the U.S. Army in 1967.

After retiring from the Celtics in 1969, Russell agreed to become coach and general manager of the Seattle Supersonics where he led the franchise to it’s first-ever playoff berth in the 1974-75 season. He left the Sonics in 1977 but maintained a residence on Mercer Island, a Seattle suburb, where he still lives today. In 2011 Bill Russell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

Russell left an excellent foundation for future franchise success, evidenced when New York native Lenny Wilkens took over as coach and led the Supersonics to an NBA Finals appearance at the end of the 1977-78 season. The next year the Sonics won the NBA Championship, defeating the Washington Bullets in six games. This victory represents King County’s first major professional sports championship, and Wilkins became only the second African American head coach to win an NBA title behind Bill Russell. Other Sonics players, including Gus Williams, Donald “Slick” Watts and “Downtown” Fred Brown, became popular athletes in the city.

In the 1990s Sonics point guard Gary Payton and forward Shawn Kemp formed a dynamic duo that electrified Seattle fans and the entire NBA. That team’s success would culminate with an appearance in the 1996 NBA Finals against the Chicago Bulls and Michael Jordan, considered by many to be the best player of all time. The Sonics lost the best of seven series four games to two, and Jordan was named Most Valuable Player of the Finals.

The tradition of professional basketball in King County continued with the birth of the Seattle Storm of the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) in 2000. In 2004 the Storm defeated the Connecticut Sun two games to one in a best of three series to claim the franchise’s first WNBA Championship. Storm guard Betty Lennox was named Finals MVP. Six years later All-Star forward Swin Cash and the Storm won a second WNBA championship, defeating the Atlanta Dream three games to none in a best of five series.

Another athletic pioneer was Warren Moon, the University of Washington football team’s first black quarterback. Moon led the Huskies to the 1978 Rose Bowl. In an era where scouts and coaches refused to believe African Americans had the mental ability to play quarterback, Husky coach Don James gave Moon the opportunity no one else would. The move paid off with Moon leading Washington to a 27-20 victory over the University of Michigan in the Rose Bowl played in Pasadena, California and earning Most Valuable Player honors to finish his Husky career.

Moon eventually won five Canadian Football League Grey Cup Championships before he returned to the United States to play in the National Football League. Moon played quarterback with the Seattle Seahawks from 1997 to 1998. Over his 16 year NFL career Moon was named to the Pro Bowl nine times, was NFL Man of the Year in 1989, NFL Offensive Player of the Year in 1990, and inducted into the Professional Football Hall of Fame in 2006.

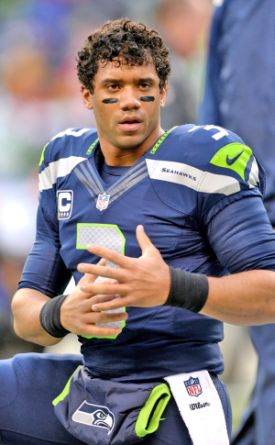

Over the years the team had other African American star athletes including defensive lineman Cortez Kennedy (1992 NFL Defensive Player of the Year, 2012 Pro Football Hall of Fame Inductee), running back Shaun Alexander (2005 NFL Most Valuable Player), and offensive lineman Walter Jones (named to nine Pro Bowls, four-time First Team All-Pro, 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame Inductee). On February 2, 2014, Russell Wilson became only the second starting African American quarterback to win a Super Bowl when he led the Seahawks over the Denver (Colorado) Broncos 43-8 for the city’s second major professional sports championship, Superbowl XLVIII, played in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

In 2007 Seattle was awarded a Major League Soccer (MLS) franchise, Seattle Sounders FC. Standout players have included Federal Way native Lamar Neagle and Nigerian-born Obafemi Martins. In addition Sounders FC defender Deandre Yedlin, a Seattle native and O’Dea High School graduate, was named to the United States Men’s National Team and played in the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.

Ken Griffey Jr. thrilled Seattle Mariners baseball fans in the 1990s with his exceptional athleticism and flair for the game. Griffey led the Mariners to some of their best seasons in the mid-1990s including two divisional titles in 1995 and 1997. He won Most Valuable Player of the All-Star Game in 1992, the American League MVP in 1997, and in 1999 was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century team. In 1990, years before the team’s success, Ken Griffey, Jr., played with his father, Ken Griffey, Sr., for the Mariners, a rare time when father and son were on the same professional baseball team.

While it would be an exaggeration to claim that professional athletes such as Russell, Wilkins, Moon, Griffey, Payton, Kemp, or Wilson have changed the racial climate of Seattle or generated more opportunity for most African Americans in the county, there is no denying that their presence and remarkable performances have influenced popular culture both in the region and the nation.

Popular culture at the local and national levels has also been influenced by Seattle’s particular version of hip-hop music. Hip-hop began in the streets of the south Bronx, New York City in the late 1970s and arrived in King County with the release of the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in late 1979. By 1981 the Emerald Street Boys, Captain Crunch, Sugar Bear, and Sweet J were among the first groups to earn a reputation as hip-hop performers around the city of Seattle.

Drawing inspiration from the Emerald Street Boys, Anthony “Sir Mix-A-Lot” Ray, a Seattle native born in 1963, began playing weekend nights regularly first at the Rainier Vista Boys and Girls Club in South Seattle and then later at the Rotary Boys and Girls Club in the Central District. It was there that he met “Nasty” Nes Rodriguez, a local Filipino American radio DJ and host of Fresh Tracks, the West Coast’s first rap radio show on Seattle station 1250 AM KKFX (KFOX).

Impressed by what he saw, Rodriguez invited Mix-A-Lot onto his show to air his music, and Mix-A-Lot quickly became the station’s most requested artist. The duo teamed up to start NastyMix Records, and in 1987 released Sir Mix-A-Lot’s first hit single “Posse on Broadway” which introduced black Seattle’s hip-hop culture to the rest of the world. Sir Mix-A-Lot, however, is best known for the single “Baby Got Back” from his 1992 album Mack Daddy. The song and accompanying video, promoting his preference for women with curves, was played on MTV only at night because of its suggestive nature, a controversy that helped make the song more popular. “Baby Got Back” sold over two million copies, was the number one song on the Billboard pop chart for five weeks, and won the 1993 Grammy Award for Best Solo Rap Performance.

Another local rapper, Seattle native Ishmael Butler by 1993 became “Butterfly,” the leader of the group Digable Planets. They are best known for their 1993 song “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” which won the 1994 Grammy Award for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group. In 2009 Butler reemerged as “Palaceer Lazaro,” leader of the critically acclaimed experimental hip-hop collective Shabazz Palaces.

As a whole the King County hip-hop scene represents an eclectic group of artists and interests which has developed a reputation for diversity and ingenuity. One example is the Seattle based multiracial breakdance crew Massive Monkees. Born out of the Jefferson Park Community Center on Beacon Hill in 1999, Massive took first place in the 2004 World B-Boy Championships held at Wembley Stadium in London, England. They appeared on season four of the hit MTV show “America’s Best Dance Crew,” and in 2012 Massive Monkees became the first American crew to win the prestigious “R16” World Championships in Seoul, South Korea.

As a white artist raised and mentored by the local scene, Ben “Macklemore” Haggerty represents another example of how hip-hop in King County has transcended racial boundaries. After having two singles, “Thrift Shop” and “Can’t Hold Us,” reach number one on the Billboard chart in 2013, he won trophies for Best Rap Song, Best New Artist, Best Rap Performance, and Best Rap Album at the 2014 Grammy Awards.

Black King County’s cultural influence extended far beyond sports and hip-hop as a number of leading artists chose to call the county home. They included visual artists Jacob Lawrence and his wife, Gwendolyn Knight. Lawrence’s career spanned the period from the Harlem Renaissance to his death in 2000. The couple relocated from New York to Seattle in 1971 when Lawrence agreed to take a teaching position at the University of Washington. Knight would become known for figure compositions and portraits of humans and animals. Lawrence was an expressionist painter who produced numerous original works, including a series on black pioneer settler George Washington Bush for the State of Washington History Museum. The couple also mentored hundreds students throughout the region.

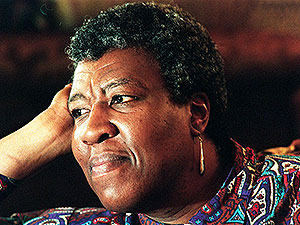

In moving to the area Lawrence and Knight had joined another prominent King County artistic couple, James and Janie Washington. The Washingtons arrived in Seattle in 1944 from Little Rock, Arkansas and moved into a modest home in the Central District. Janie was a practicing nurse and James produced a series of world renowned sculptures until his death in 2000. The Washington home is now a Seattle landmark and museum as well as a site for production by younger generations of artists.