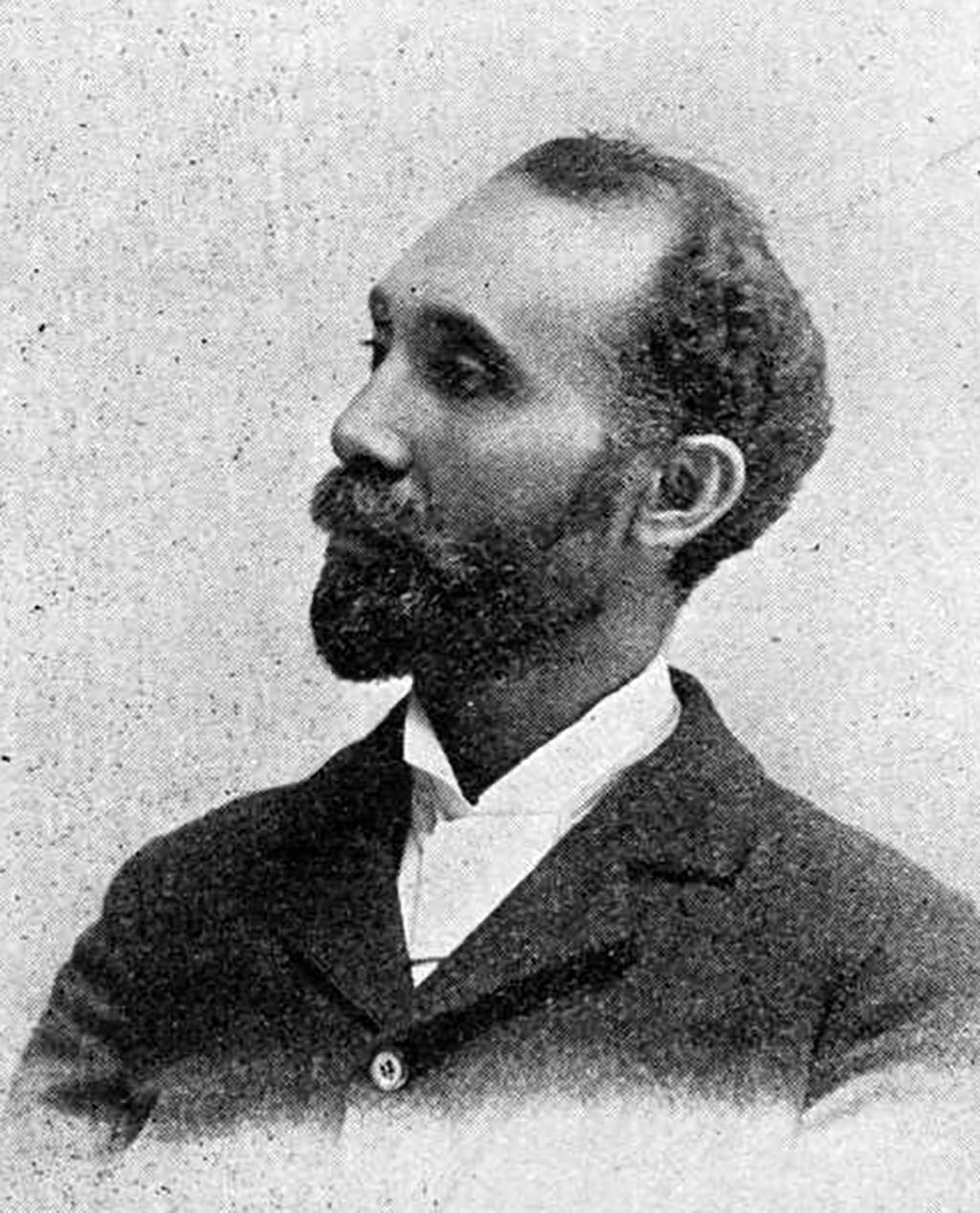

Today Ferdinand L. Barnett is best known as the husband of anti-lynching crusader, Ida Wells Barnett. However by 1879, Barnett, a graduate of Chicago’s College of Law and editor the Chicago Conservator, the city’s first black newspaper, which he founded in 1878, was one of a rising number of post-Reconstruction black leaders. On May 6 9, 1879, at a national conference of African American men meeting in Nashville, Tennessee where most of the issues discussed related to Southern black poverty and anti-black violence in the region, Barnett, the delegate from Chicago gave a speech which called for race unity as the necessary precondition of African American progress. His address specifically called African Americans to unite both politically and economically; to set aside jealousy and in fighting, to assist the poor and support black-owned businesses which in turn would hire African American workers and urged the black schools of the South to be staffed by African American teachers not only to build a middle class but also because he believed these teachers would be especially committed to education and racial uplift. Far from being unique, Barnett’s calls echoed earlier leaders such as Henry Highland Garnet and anticipated future leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W.E. B. DuBois. His speech appears below.

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen of the Conference: The subject assigned me is one of great importance. The axioms which teach us of the strength in unity and the certain destruction following close upon the heels of strife and dissension, need not be here repeated. Race elevation can be attained only through race unity. Pious precepts, business integrity, and moral stamina of the most exalted stamp, may win the admiration for a noble few, but unless the moral code, by the grandeur of its teachings, actuates every individual and incites us as a race to nobler aspirations and quickens us to the realization of our moral shortcomings, the distinction accorded to the few will avail us nothing. The wealth of the Indies may crown the efforts of fortune’s few favored ones. They may receive all the homage wealth invariably brings, but unless we as a race check the spirit of pomp and display, and by patiently practicing the most rigid economy, secure homes for ourselves and children, the preferment won by a few wealthy ones will prove short lived and unsatisfactory. We may have our educational lights here and there, and by the brilliancy of their achievements they may be living witness to the falsity of the doctrine of our inherited inferiority, but this alone will not suffice. It is a general enlightenment of the race which must engage our noblest powers. One vicious, ignorant Negro is readily conceded to be a type of all the rest, but a Negro educated and refined is said to be an exception. We must labor to reverse this rule; education and moral excellence must become general and characteristic, with ignorance and depravity for the exception.

Seeing, then, the necessity of united action and universal worth rather than individual brilliancy, we sorrowfully admit that race unity with us is a blessing not yet enjoyed, but to be possessed. We are united only in the conditions which degrade, and actions which paralyze the efforts of the worthy, who labor for the benefit of the multitude. We are a race of leaders, everyone presuming that his neighbor and not himself was decreed to be a follower. To day, if any one of you should go home and announce yourself candidate for a certain position, the following day would find a dozen men in the field, each well prepared to prove that he alone is capable of obtaining and filling the position. Failing to convince the people, he would drop out [of] the race entirely or do all in his power to jeopardize the interest of a more successful brother.

Why this non fraternal feeling? Why such a spirit of dissension? We attribute it, first, to lessons taught in by gone days by those whose security rested in our disunion. If the same spirit of race unity had actuated the Negro which has always characterized the Indian, this Government would have trembled under the blow of that immortal hero, John Brown, and the first drop of fratricidal blood would have been shed, not at Fort Sumter, but at Harper’s Ferry. Another cause may be found in our partial enlightenment. The ignorant man is always narrow minded in politics, business or religion. Unfold to him a plan, and if he cannot see some interest resulting to self, however great the resulting good to the multitude, it meets only his partial approbation and fails entirely to secure his active co operation. A third reason applies, not to the unlearned, but to the learned. Too many of our learned men are afflicted with a mental and moral aberration, termed in common parlance “big headed.” Having reached a commendable degree of eminence, they seem to stand and say, “Lord, we thank Thee we are not as other men are.” They view with perfect unconcern the struggles of a worthy brother; they proffer him no aid, but deem it presumption in him to expect it. They may see a needed step but fail to take it. Others may see the necessity, take steps to meet it, and call them to aid. But, no; they did not lead; they will not follow, and half of their influence for good is sacrificed by an insane jealousy that is a consuming fire in every bosom wherein it finds lodgment.

A few of the prominent causes which retard race unity having been noticed, let us look for the remedy. First, our natural jealousy must be overcome. The task is no easy one. We must look for fruits of our labor in the next generation. With us our faults are confirmed. An old slave once lay dying, friends and relatives were gathered around. The minister sat at the bedside endeavoring to prepare the soul for the great change. The old man was willing to forgive every one except a certain particularly obstreperous African who had caused him much injury. But being over persuaded he yielded and said: “Well, if I dies I forgives him, but if I lives dat darkey better take care.” It is much the same with us; when we die our natures will change, but while we live our neighbors must take care. Upon the young generation our instruction may be effective. They must be taught that in helping one another they help themselves; and that in the race of life, when a favored one excels and leads the rest, their powers must be employed, not in retarding his progress, but in urging him on and inciting others to emulate his example.

We must dissipate the gloom of ignorance which hangs like a pall over us. In former days we were trained in ignorance, and many of my distinguished hearers will remember when they dare not be caught cultivating an intimate acquaintance with the spelling book. But the time is passed when the seeker after knowledge is reviled and persecuted. Throughout the country the public school system largely obtains; books without number and papers without price lend their enlightenment; while high schools, colleges and universities all over our broad domain throw open their inviting doors and say, “Whosoever will may come.”

We must not fail to notice any dereliction of our educated people. They must learn that their duty is to elevate their less favored brethren, and this cannot be done while pride and conceit prevent them from entering heartily into the work. A spirit of missionary zeal must actuate them to go down among the lowly, and by word and action say: “Come with me and I will do you good.”

We must help one another. Our industries must be patronized, and our laborers encouraged. There seems to be a natural disinclination on our part to patronize our own workmen. We are easily pleased with the labor of the white hands, but when the same is known to be the product of our own skill and energy, we become extremely exacting and hard to please. From colored men we expect better work, we pay them less, and usually take our own good time for payment. We will patronize a colored merchant as long as he will credit us, but when, on the verge of bankruptcy he is obliged to stop the credit system, we pass by him and pay our money to the white rival. For these reasons our industries are rarely remunerative. We must lay aside these “besetting sins” and become united in our appreciation and practical encouragement of our own laborers.

Our societies should wield their influence to secure colored apprentices and mechanics. By a judicious disposition of their custom, they might place colored apprentices in vocations at present entirely unpracticed by us. Our labor is generally menial. We have hitherto had a monopoly of America’s menial occupations, but thanks to a progressive Caucasian element, we no longer suffer from that monopoly. The white man enters the vocations hitherto exclusively ours, and we must enter and become proficient in professions hitherto exclusively practiced by him.

Our communities must be united. By concerted action great results can be accomplished. We must not only act upon the defensive, but when necessary we should take the offensive. We should jealously guard our every interest, public and private. Let us here speak of our schools. They furnish the surest and swiftest means in our power of obtaining knowledge, confidence and respect. There is no satisfactory reason why all children who seek instruction should not have full and equal privileges, but law has been so perverted in many places, North and South, that sanction is given to separate schools; a pernicious system of discrimination which invariably operates to the disadvantage of the colored race. If we are separate, let it be from “turret to foundation stone.” It is unjust to draw the color line in schools, and our communities should resent the added insult of forcing the colored pupils to receive instructions from the refuse material of white educational institutions. White teachers take colored schools from necessity, not from choice. We except of course those who act from a missionary spirit.

White teachers in colored schools are nearly always mentally, morally, or financially bankrupts, and no colored community should tolerate the imposition. High schools and colleges are sending learned colored teachers in the field constantly, and it is manifestly unjust to make them stand idle and see their people taught by those whose only interest lies in securing their monthly compensation in dollars and cents. Again, colored schools thrive better under colored teachers. The St. Louis schools furnish an excellent example. According to the report of Superintendent Harris, during the past two years the schools have increased under colored teachers more than fifty per cent, and similar results always follow the introduction of colored teachers. In case of mixed schools our teachers should be eligible to positions. They invariably prove equal to their requirements. In Detroit and Chicago they have been admitted and proved themselves unquestionably capable. In Chicago their white pupils outnumber the colored ten to one, and yet they have met with decided success. Such gratifying results must be won by energetic, united action on the part of the interested communities. White people grant us few privileges voluntarily. We must wage continued warfare for our rights, or they will be disregarded and abridged.

Mr. President, we might begin to enumerate the rich results of race unity at sunrise and continue to sunset and half would not be told. In behalf of the people we are here to represent, we ask for some intelligent action of this Conference; some organized movement whereby concerted action may be had by our race all over the land. Let us decide upon some intelligent, united system of operation, and go home and engage the time and talent of our constituents in prosperous labor. We are laboring for race elevation, and race unity is the all important factor in the work. It must be secured at whatever cost. Individual action, however insignificant, becomes powerful when united and exerted in a common channel. Many thousand years ago, a tiny coral began a reef upon the ocean’s bed. Years passed and others came. Their fortunes were united and the structure grew. Generations came and went, and corals by the million came, lived, and died, each adding his mite to the work, till at last the waters of the grand old ocean broke in ripples around their ireless heads, and now, as the traveler gazes upon the reef, hundreds of miles in extent, he can faintly realize what great results will follow united action. So we must labor, with the full assurance that we will reap our reward in due season. Though deeply submerged by the wave of popular opinion, which deems natural inferiority inseparably associated with a black skin, though weighted down by an accursed prejudice that seeks every opportunity to crush us, still we must labor and despair not patiently, ceaselessly, and unitedly. The time will come when our heads will rise above the troubled waters. Though generations come and go, the result of our labors will yet be manifest, and an impartial world will accord us that rank among other races which all may aspire to, but only the worthy can win.